Opinion: What’s more important, freedom or safety? Mothering in the shadow of Charlie Hebdo

- Share via

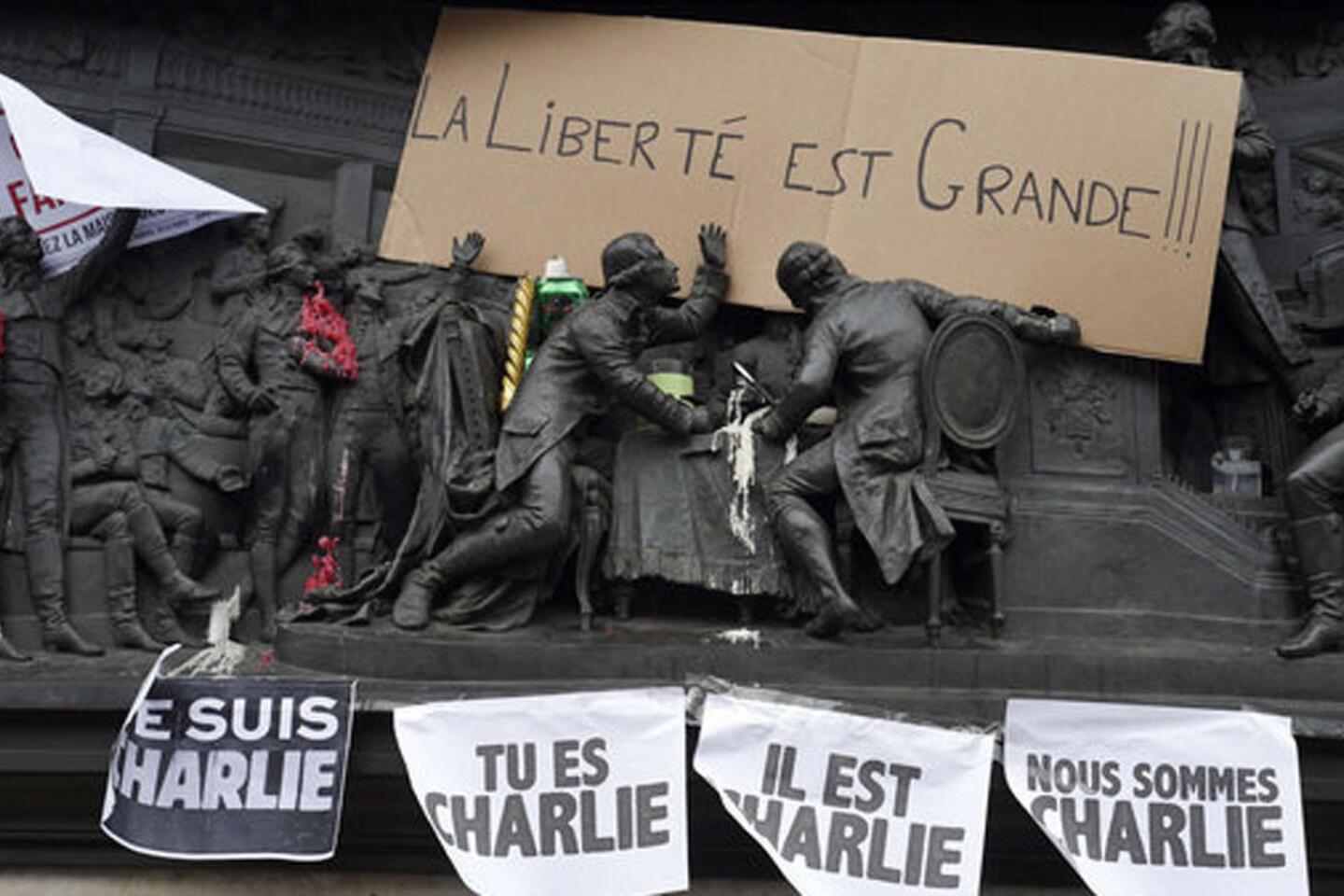

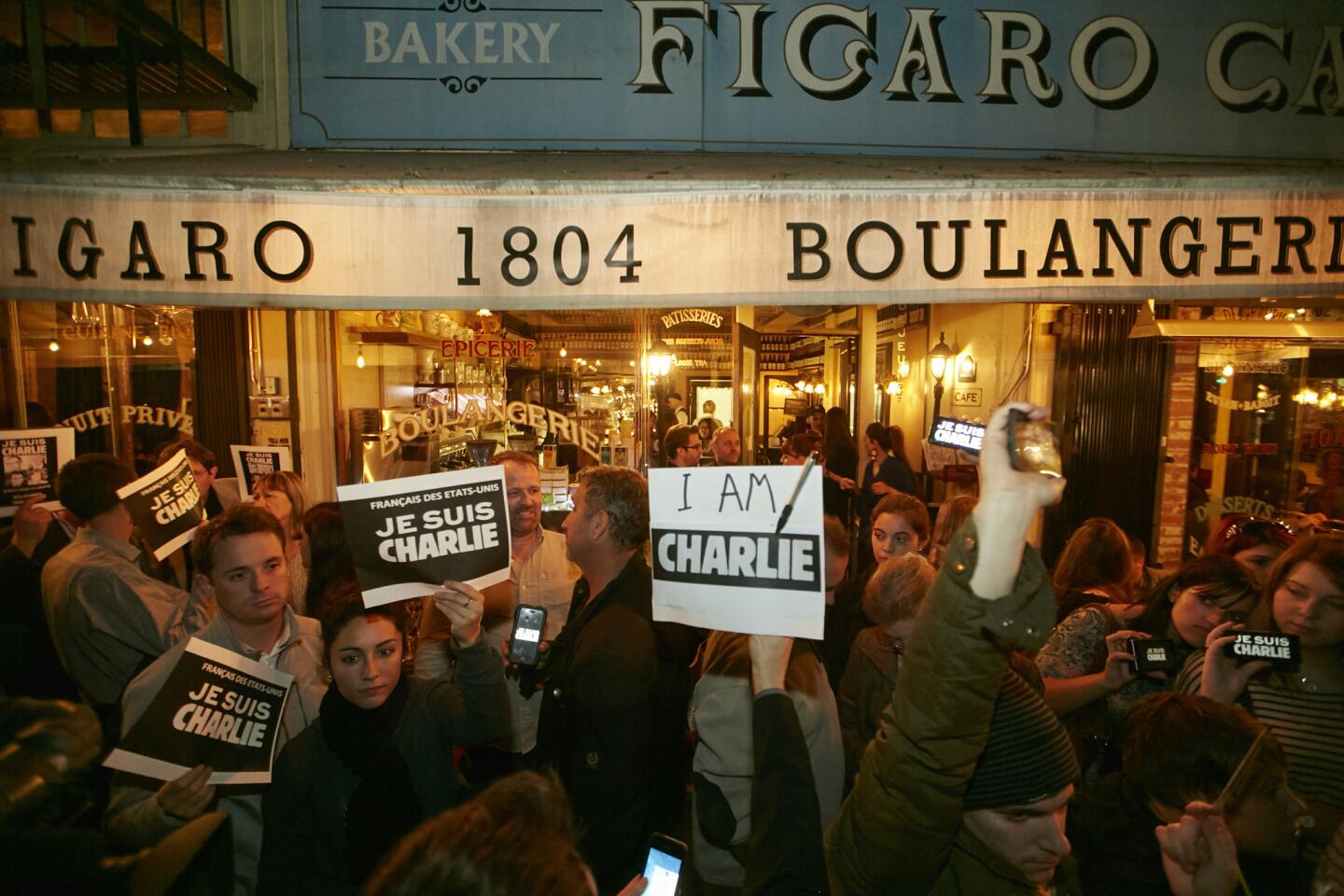

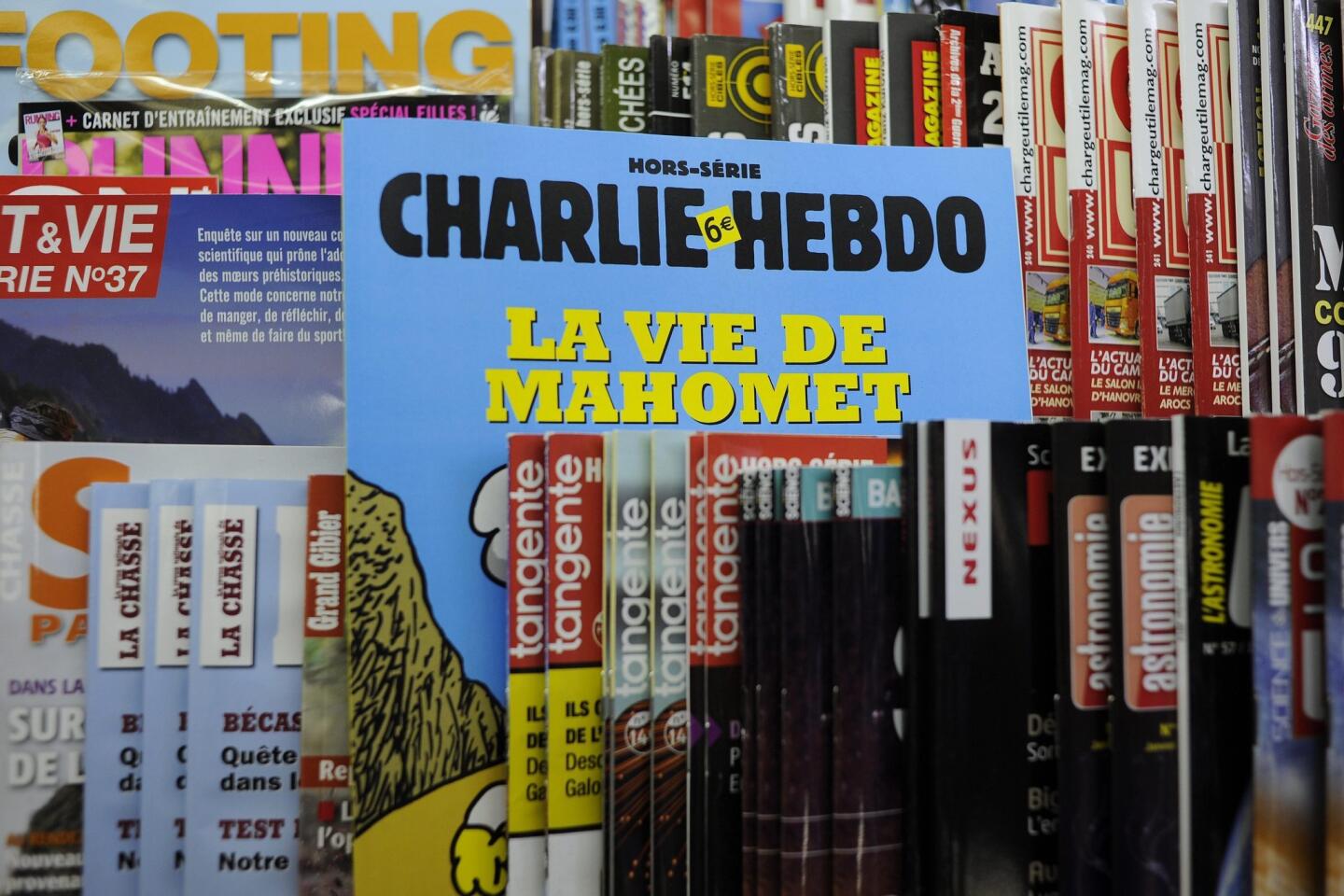

Watching the news on the Paris massacre at Charlie Hebdo last week, my son asked, “Mom, what would you say NOW is more important, freedom or safety?” At 17, Theo adamantly supports Hebdo’s right to print irreverent and inflammatory images. But I knew he was referring to more than just the recent devastating events in France. This was a conversation we’d begun 10 years earlier.

At that time, a friend of mine was camped out in our guest room after having fled her violent husband with her 6-year-old son. Each morning, while Theo went off to school, my friend left for her job, accompanied by her son. She’d pulled him out of school until she could find a new place to live, and so he traveled with her, clutching Billy Blazes, a Rescue Hero toy that was popular in the years right after 9/11. To Theo, this little boy who didn’t have to go to first grade, but instead got to bring action figures to work with Mommy, must have looked impossibly free. Still, Theo sensed the precariousness of his friend’s situation. One night, as I was putting Theo to bed, he asked the question for the first time: “Mom, what is more important, freedom or safety?”

I stood at my son’s door, pondering how to answer these very adult words from my child. I’d grown up with a father who, having fled Nazi Germany, believed passionately in freedom. In 1970, my father, the eminent art historian Peter Selz, testified in a lawsuit filed over the publication and exhibition of cartoonist R. Crumb’s explicit sexual illustrations. During the court case, stack of these comic books surrounded my father’s desk. At 8 years old, I became familiar with Crumb’s depictions of naked people. As the director of the Berkeley Art Museum, Dad curated a show on caricatures, “The American Presidency in Political Cartoons,” satirizing all our leaders. Dad wrote about Degenerate Art, the art the Nazis banned, stole and destroyed for its flagrant depiction of expression. Like the art historian Meyer Schapiro, my father applauded art as a form of personal liberation and “the only guarantee of political and ethical integrity.” Then, in 1978, he financially supported the ACLU’s defense of a Neo-Nazi groups right to demonstrate, even though he was himself a Jew. Without the 1st Amendment granting the freedoms of speech, press and the right to assemble peacefully, my father insisted, none of us could ever be truly safe. This was the path that had led him out of the holocaust all the way to Berkeley, the home of the free speech movement.

Yet, as a child, my father’s world of protest marches, free love and intense, often brutal art, felt dangerous to me. At any moment, I might discover something frightening: pictures of sex, of war, of concentration camps. I accompanied him on peace marches where the armed National Guard showed up. Now I was a mother of a little boy whom I wanted to protect, from physical harm, from instability, but also from knowing and seeing too much too soon.

In Theo’s doorway, I weighed my words. Eventually I said, “Safety.” And then, because Theo had asked me a complicated question, I added, “Without safety you can’t really be free.” But I knew, even then, that this was only a temporary answer.

As Theo grew, we continued to discuss this topic as the parameters of what was free and what was safe shifted. He was free to walk to school, to determine his bedtime, to drive. Now, a typical teenager, he pushes away from the nest of his home towards independence in the larger world. In his political beliefs, Theo reminds me of my father, adamant that no matter what the cost, it is more important to speak his mind than it is to be safe.

For years, I struggled to live up to the standard my father set for me. As a parent, I was torn. Although my impulse was to shelter my son at any cost, I also tried to raise Theo to think for himself even when he disobeyed me and stayed out way past curfew. But nothing really bad ever happened to him. The fact is, that until he was 15, my father’s life as an affluent German Jew in Munich was as predictable and secure as a timepiece.

The more that I think about my son’s question, the more I believe that freedom and safety are not absolutes but are contingent upon each other, inextricably intertwined like a Mobius strip. I stroke Theo’s hair. He grew up in a fairly benign environment. No bombs fell over his head while he slept. We have been lucky. Perhaps if he had grown up in a war zone, he would worry more about protection than he does about self-expression.

Gabrielle Selz is the author of the 2014 memoir “Unstill Life: A Daughter’s Memoir of Art and Love in the Age of Abstraction.” gabrielleselz.com

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.