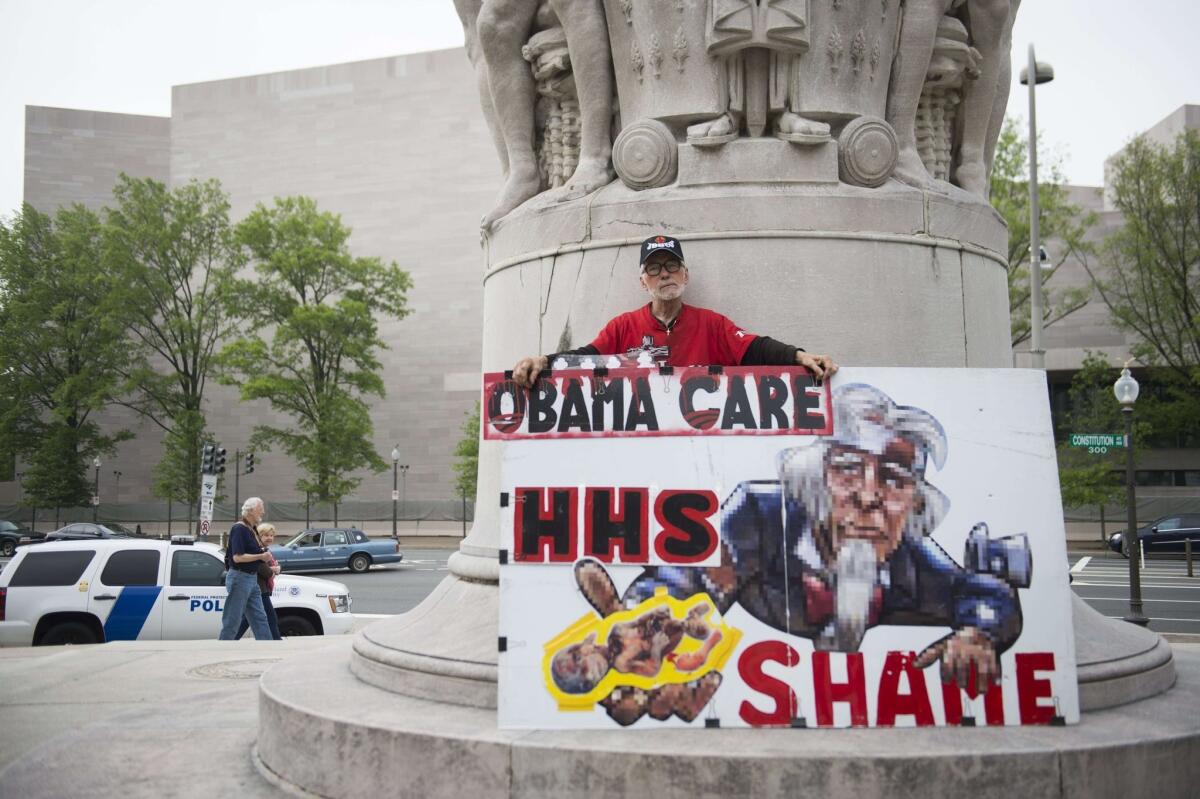

Opinion: Obamacare may prevail in court, but can it survive rising premiums?

- Share via

A consistent theme in the legal challenges to the 2010 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act is that Democrats in Congress or the Obama administration cheated in some way to enact or implement the law. The arguments go something like this: Congress overstepped its constitutional authority to regulate interstate commerce by requiring Americans to buy insurance. The administration improperly rewrote the law by issuing rules that don’t comply with the law’s text. And in two cases heard Thursday in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, Democrats are alleged to have ignored the constitutional requirement that all revenue bills originate in the House, and the administration is accused of breaking the rules on religious freedom in its zeal to make insurance plans cover contraception with no out-of-pocket costs.

The argument with the best chance of prevailing is the complaint by church-affiliated employers against just a portion of the law, the contraception mandate (for the record, The Times’ editorial board supports the mandate with the narrow exemptions the administration has provided). The other challenges, which strike at the core of the law, have already been rejected or seem like long shots. The true existential threat to Obamacare is much more likely to come from rising health insurance premiums. But more on that later.

Here’s what I mean by a legal long shot. One of the cases heard Thursday is a lawsuit by an artist in Washington state named Matt Sissel, who initially challenged the individual mandate on the grounds that it violated the Constitution’s commerce clause. When the Supreme Court held that the mandate was a constitutional use of Congress’ power to tax, Sissel and his lawyers at the Pacific Legal Foundation shifted gears, arguing that the measure originated in the Senate, not the House, in violation of the origination clause in Article I. For those who don’t have Article I memorized, said clause states, “All Bills for raising Revenue shall originate in the House of Representatives; but the Senate may propose or concur with Amendments as on other Bills.” (The founders really liked capital letters.)

I blogged about the lawsuit last year, after District Court Judge Beryl A. Howell (one of President Obama’s appointees) rejected Sissel’s claim. Howell wrote that the origination clause challenge failed because the purpose of the ACA was not to raise revenue, and because the bill in question (HR 3590) did, in fact, originate in the House. Granted, the House-passed version would have extended a tax break for veterans, but it also included provisions to raise revenue to offset the tax break’s cost.

The Pacific Legal Foundation argues in its appeal that Howell misinterpreted the precedents on the issue, which it claims require any Senate amendment to a House revenue bill to be relevant to the topic addressed by the House. But if the foundation is correct, it would read a germaneness requirement into the origination clause that the founders didn’t write.

More fundamentally, the idea of an individual mandate enforced through tax penalties started in the House, which passed its version of the ACA before the Senate started its debate. So why didn’t the Senate simply take up that House bill, HR 3962? Jim Manley, who was Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid’s main spokesman at the time, suggested that the House bill had an insurmountable problem: it “included a public option that was never going to get enough votes to get out of the Senate.” So Reid decided instead to gut an unrelated tax bill from the House, HR 3590, and use that as the vehicle for Senate’s healthcare proposal, Manley said.

The “public option” was a Medicare-style government-run insurance plan that liberal Democrats wanted to make available through the state exchanges. When Sen. Joe Lieberman (I-Conn.) indicated that he would filibuster the bill if it included such a provision, the public option was no longer an option.

Given the House’s role in proposing the individual mandate and the ridiculousness of considering the ACA a bill for raising revenue, it would be a truly strange outcome if Sissel’s lawsuit succeeded in taking down Obamacare. But a new analysis by the Avalere Health consulting firm of enrollment data at the exchanges gives opponents reason to hope that the law will founder without the courts’ help.

Although the total enrollment exceeded expectations and the percentage of uninsured Americans is dropping, Avalere’s report finds one big dark cloud on the horizon. “[S]ecular increases in the cost of medical care and in utilization of services and new medical technology make it likely that exchange plans will need to increase their prices,” the company predicted. “While the exchange markets are likely to remain competitive, and the demographic mix of enrollees has been within tolerance limits, these factors will not compensate for increases in costs in health markets. Premium increases will vary geographically, and will depend in part on the competitiveness of provider markets.”

As a result, Avalere predicted, at least some regions will see the sort of double-digit premium increases that were common in the years leading up to the last recession. Those increases would come on top of the big jump in prices many people in the individual and small-group markets faced in their 2014 policies, which reflected the higher costs the ACA’s insurance reforms imposed -- particularly on younger, healthier people who earned too much to qualify for large federal subsidies.

Those who do receive large subsidies may not complain about the premium hikes. But the faster the rates rise, the more taxpayers will have to spend on subsidies, which increase in tandem with premiums.

Of course, most Americans with insurance aren’t covered by individual or small-group policies. Instead, they’re covered either by their employer’s large-group plan or a government program (for example, Medicare or Medicaid). Unlike the individual insurance market, large group and government plans already accepted all applicants regardless of preexisting conditions, and they already covered most, if not all, of the essential health benefits identified by the ACA. So they’ve not come under the same cost pressure.

But as we saw last fall, the cost of individual policies gets a lot of attention from the media. And even if the next round of price hikes has little or nothing to do with the 2010 law, many people will still blame Obamacare. That could erode public support for the law, and its defenders in Congress, even further.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.