Opinion: How my interview with O.J. almost ended in a fistfight

- Share via

As 1993 wound down, Leo Wolinksy, then the Metro editor at The Times, asked me to put together a story that would take stock of the period we’d just been through: A few days earlier, a jury had delivered a mishmash of verdicts against those involved in the beating of Reginald O. Denny during the 1992 riots, ending a cycle of courtroom dramas that included the 1991 beating of Rodney King, the 1992 acquittals of the officers in that case on most counts; the riots that ensued; and the federal convictions of two of those same officers. The period also featured the ouster of one police chief and the hiring of another, as well as the election of a new mayor and four new council members. By the end of 1993, it felt to many people here as though we’d all been through the wringer but perhaps had finally gotten through it. My story, “Weary L.A. Looks to Its Future,” ran on Dec. 8, 1993. It felt like a period at the end of a long sentence.

------------

FOR THE RECORD

June 12, 8:58 p.m.: An earlier version of this post said that Jim Newton’s story “Weary L.A. Looks to Its Future” ran on Dec. 8, 2003. It ran on Dec. 8, 1993.

------------

Six months later, 20 years ago today, the bodies of Nicole Brown Simpson and Ronald Goldman were found in Brentwood. I was on my way home from my brother’s law school graduation when I heard the news; for the next 15 months, I was the lead reporter for The Times on the case.

The murder trial of O.J. Simpson had none of the political or social import of the police and riot cases, but it produced a bulging vessel into which all kinds of issues poured. Race, class, spousal abuse, the death penalty, the reliability of DNA evidence, the trustworthiness of the LAPD, the competence of the district attorney’s office — all had their day in the 14 months that began on June 12, 1994, and ended on Oct. 3, 1995.

It wasn’t pretty. Much of the coverage had a giddy quality to it, as if this were an examination of rich and famous L.A. rather than an attempt to assign responsibility for two murders. The courthouse was ringed with television trucks for months; parties in other trials would snake their way over cables and around television personalities to get their day in court.

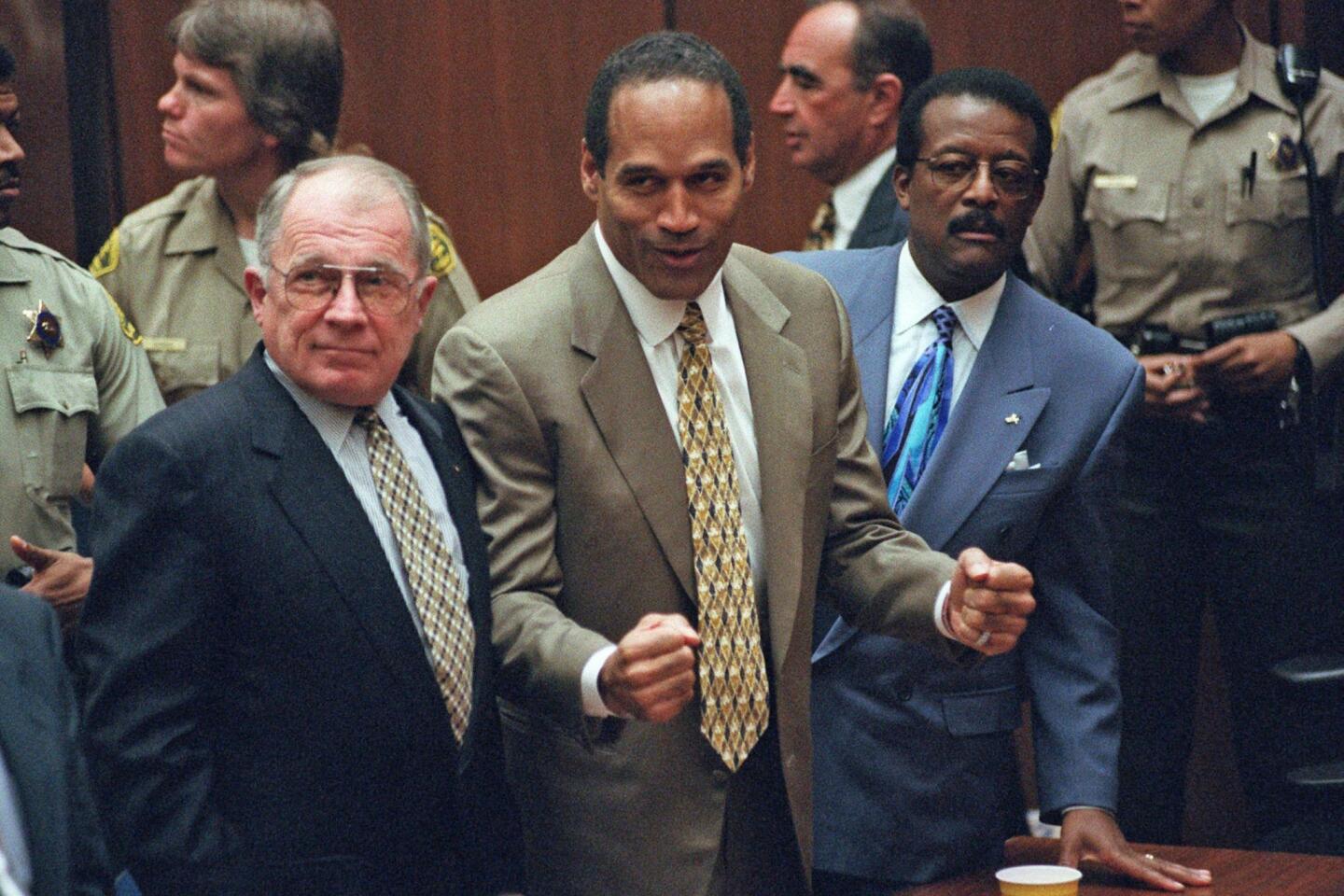

As anyone who followed the trial knows, it was an exceptionally long and occasionally tedious affair. By the time it was over, I’d written several hundred stories, and I was there when the jury delivered its not-guilty verdict. I watched Simpson clench his fists and mutter the words “Thank you” as Ron Goldman’s father dissolved in despair. It was, Goldman said, the second worst day of his life, exceeded only by the day he heard his son had been murdered.

I never spoke directly with Simpson until after it was over (it is testament to Johnnie L. Cochran’s charm and persuasiveness that he kept me believing I might have a chance to interview his client). But a few months after the trial ended, I finally sat down with Simpson.

It was February 1996, and my colleague Henry Weinstein and I were working in the newsroom when we heard Simpson was on TV. We flipped on the set between our desks and listened as Simpson complained to CNN about The Times’ coverage of his civil case. Figuring that if he had a beef with the paper, he might want to tell us directly, we hopped in my car and hustled out to Simpson’s Brentwood home. There, we rang the buzzer, and, to our amazement, he invited us in.

Simpson led us to a breakfast nook, and we spent 90 minutes talking. He wore a football Hall of Fame ring. Behind him were an array of photographs picturing him with famous people — Richard Nixon, Joe Frazier, Muhammad Ali, etc.

Parts of the interview were weird. When I asked him why his hands were cut at the time of his arrest, he pointed to a cut on one of my hands and insisted that I explain my cut first. He deflected some questions about the case by promising he would tell all in an upcoming videotape, which he was going to sell for $29.95 (“Call 1-800-OJTELLS,” he kept repeating). And when we asked about whether he was angry with Nicole, his ex-wife, after their breakup, he responded that he was not, adding with a chuckle: “My handicap went down a few strokes in May after we broke up.”

But one moment from that day remains with me with particular clarity, these 20 years later. I was recovering from a nasty ear infection at the time and was relying on my tape recorder to supplement my notes (I shouldn’t have worried; Henry is a prodigious note-taker and wouldn’t have missed anything). Simpson at first agreed to the tape recorder, but then he abruptly changed his mind, saying he was worried we’d sell it to a radio station and it would show up on the air. He grabbed the recorder, and I, fearful that I was about to lose the record of our interview, instinctively jumped up to grab it back. He flashed with anger, and for a moment, we looked hard at each other.

The moment passed — he gave me back the tape — but there was an instant where I thought I might get into a fistfight with O.J. Simpson. That would not have ended well for me, but it certainly would have brought that period to a perfect conclusion. And Henry would’ve had a hell of a story.

Follow Jim Newton on Twitter at @newton_jim

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.