Opinion: What L.A. County supervisors got wrong on sheriff oversight

- Share via

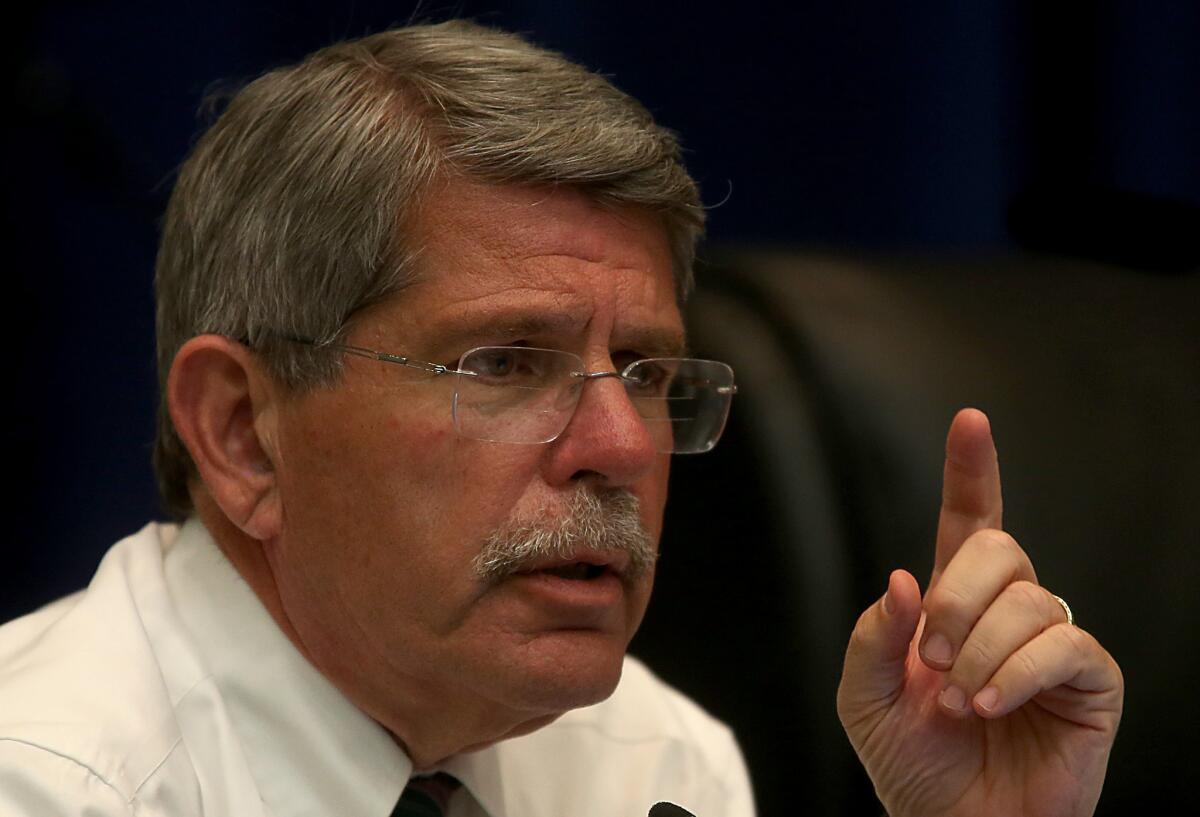

In arguing against a civilian commission to oversee the Sheriff’s Department, Richard Drooyan on Tuesday read the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors a key passage from the report on jail violence he helped write in 2012. Such a commission, he said, “is not necessary if the Board of Supervisors continues to put a spotlight on conditions in the jails and establishes a well structured and adequately staffed OIG” — meaning the new Office of Inspector General.

They are the correct words to draw from the findings and recommendations of the Citizens Commission on Jail Violence, but they should direct readers to the opposite conclusion.

An oversight commission is not necessary if — and it’s the key “if” — the supervisors continue to focus on the jails and if they establish a well-structured and adequately staffed OIG.

In fact, as to the first “if,” the long, sorry record of the Board of Supervisors’ failed oversight of the Sheriff’s Department shows that its attention is too unfocused over time to properly do the job. That’s the whole point: Los Angeles County is facing federal court jurisdiction over treatment of inmates, has seen six deputies convicted of obstructing an FBI investigation and a dozen others indicted on various charges, and is paying out millions of dollars in lawsuit verdicts and settlements because the board was inadequate to the task of oversight.

It’s not that the supervisors weren’t on notice of the problems, which were detailed for them every six months, along with recommendations, by Special Counsel Merrick Bobb. They were indeed on notice, but somehow lacked the will or the ability to do much about it.

Now, after rejecting a civilian oversight commission on Tuesday, a majority of the supervisors insist that everything will change. They’ve learned their lesson. They’ll do better. They really mean it this time.

Or, they’ll be more responsive because they now have an inspector general instead of a special counsel. That brings us to the second “if” of the Jail Commission’s statement: if the board “establishes a well-structured and adequately staffed OIG.”

The board on Tuesday did in fact adopt an ordinance — half a year after hiring Max Huntsman as the first inspector general — that finally defines some of his duties. But they early on rejected the Jail Commission’s recommendations to properly structure the position to ensure its independence and effectiveness.

The recommendations included hiring the inspector general “for a set term of years and be subject to removal only for cause” to provide sufficient job security and autonomy. The point is to protect the IG from political influence, not just from the sheriff but from the supervisors. He should be relatively independent, and not just another department head who must count board votes to remove him or pull him off a sensitive investigation every time he makes a decision.

Plus, the commission said, the board should pick its inspector general only after a selection process that includes the public.

But the board didn’t do that, at least not in any real or meaningful way. And instead of providing job security and autonomy the board made sure that Huntsman serves at its pleasure. They can dismiss him without stating a reason.

And the supervisors made matters even worse on Tuesday by granting him an attorney-client relationship between them and him. That means any report he makes could be made, at the board’s discretion (ostensibly on the advice of their lawyer) in closed session, out of public hearing.

So we’re pretty much where we were before. In dismissing Merrick Bobb as special counsel earlier this year and hiring Max Huntsman as inspector general, the Board of Supervisors has done little more than make a personnel change. Any additional effectiveness Huntsman has will be due to ongoing negotiations with the Sheriff’s Department, not new structures and certainly not a new reporting relationship directly to the public.

There is an argument that what’s needed is not new structures or organization charts but new leaders. The jail violence and unconscionable deputy conduct happened under the nonwatchful eye of Sheriff Lee Baca, who is now gone and will be replaced after the November election, most likely by Long Beach Police Chief Jim McDonnell, if the June primary results are any indication. So, this line of thinking goes, problem solved. Or, at least, we’ll see after the new sheriff has been in office for a while whether the problem has been solved.

And likewise, Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky, the swing vote in the 3-2 vote against an oversight commission, will be gone and replaced by one of two runoff candidates, Bobby Shriver or Sheila Kuehl, both of whom have said they favor an oversight commission.

But don’t be too sure. Of course the particular people in positions of power make a great deal of difference, but that’s not all there is to it. Any sheriff, whether it be Baca, McDonnell or someone else, is likely to get his head turned when he realizes the extent of his power and responsibility. And any supervisor, once in office, is likely to believe that he or she is best positioned and has the best motivation to ensure proper behavior. Every dictator and martinet probably believed that too, and perhaps some of them were correct, but we long ago discovered the value of checks, balances and oversight to reduce the incentive to abuse power and increase the likelihood of working openly, subject to public scrutiny.

As for the argument that the board will now do a better job of oversight, that’s just a joke, but not a very funny one. Yaroslavsky insisted Tuesday that he, his colleagues and his successors just have to make more time for overseeing the Sheriff’s Department, even if it means doubling the number of their meetings.

The implication is that before, despite the 1992 Kolts Commission report that set forth many of the problems in the department today, or warnings from the Department of Justice that treatment of mentally ill prisoners fell below an acceptable standard, or the discovery that the sheriff’s expenditures of board-allocated money were so secretive that Baca hid the fact that he had actually bought his department a jet, or the astronomically high number of deputies being arrested for drunk driving, or the jail beatings — despite all that, nothing before rose to the level of requiring the Board of Supervisors to pay more attention. But things have now changed and the board will be more vigilant.

That’s just not reasonable. The deep problems with the Sheriff’s Department may have less to do with the sheriff than they do with the board, which can’t sufficiently share power or loosen its absolute control over information to safeguard the safety of county residents and the effectiveness of their tax dollars. New supervisors may change things for a short time, just as new blood always does. But the structure needs change as well, and absent an appointed sheriff or an empowered county chief executive, there must at least be oversight reporting to the public, and not merely serving the board.

Follow Robert Greene on Twitter @RGreene2

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.