MS-13 was born in L.A. No wall can keep it out

- Share via

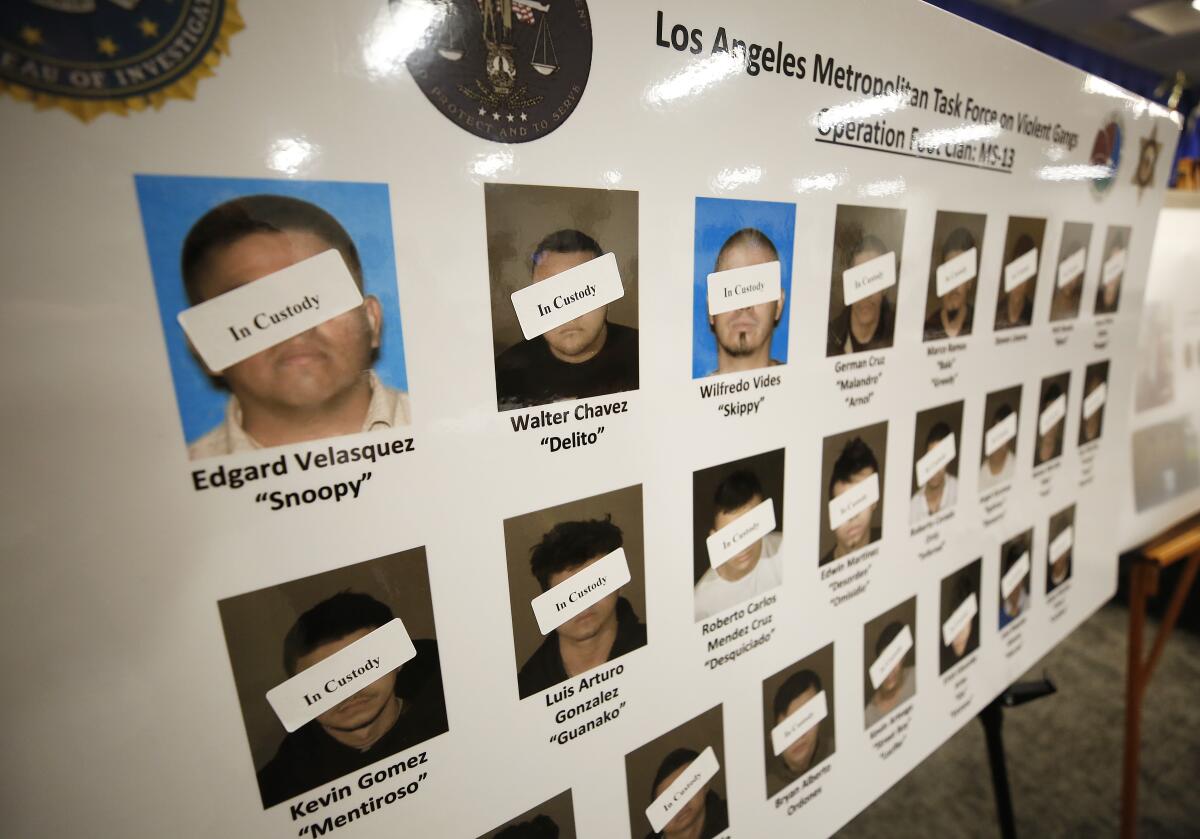

Like it or not, Los Angeles and El Salvador are inextricably linked. The latest reminder came this week with the unsealing of an indictment against 22 members of MS-13, the violent gang born on the streets of L.A. in the 1980s among young refugees from the troubled Central American nation’s civil war.

Mara Salvatrucha, as it was first known, was organized in part to protect Salvadoran immigrants trying to survive among the violent street gangs that already claimed ownership of some L.A. neighborhoods. It joined with La Eme, the prison-based Mexican Mafia, and together they fought to control criminal activities throughout Southern California.

And then in the 1990s, many members were deported back to El Salvador, where the brutality they studied here soon deepened the misery of their native country. Gangs, it was said at the time, were L.A.’s biggest international export. MS-13 became a multinational organization that expanded to other Central American countries and other U.S. cities.

According to Tuesday’s indictment, the Salvadoran government attempted to quell violence in the country by negotiating a pact with some MS-13 leaders, leading to a division in the gang and the creation of a particularly violent subset known as 503 — named for the El Salvador country code. It was members of this group, the indictment asserts, who came home to Los Angeles, operated out of Whitsett Fields Park in North Hollywood and committed a series of particularly gruesome murders. Victims were beaten to death or hacked in pieces by machete. At least one victim’s heart was ripped out of his body.

Meanwhile, in Central America, MS-13 and other gangs with L.A. roots (most notably the rival 18th Street gang) spread this brand of violence throughout not just El Salvador but Guatemala and Honduras as well. The gangs continue to recruit young men and women by force. Thousands of people fleeing the violence join others leaving the region, desperately — and perhaps ironically — seeking asylum in the U.S.

President Trump has at times tried to press his case against illegal immigration by spotlighting violent acts here by MS-13 members.

And it is indeed the case that criminals from Central America (but with deep ties to Southern California) are implicated in brutal murders around the country, including a notorious killing last year on a subway platform in Queens, New York. The killers include people who entered the United States illegally. It makes sense to keep such violent criminals out. It also makes sense to deport some violent criminals already here.

Yet if one is to make a significant dent in the problem, it will require a level of sophistication rare in U.S. political dialogue, especially in the era of Trump. It’s essential to remember that the cycle of immigration, L.A. street violence and deportation got us into this problem in the first place. We can deport criminals to other countries, but whatever violence goes with them is likely to return, especially without a significant U.S. investment in opportunity and safety for struggling people in those countries as well as their counterparts here.

It’s also important to remember that the vast majority of immigrants and would-be immigrants to the U.S. are not the criminals but more often their victims. They flee their countries to get away from the violence, and then once here — regardless of their immigration status — most try to live their lives, raise their families and operate their businesses without threats or shakedowns. No wall can keep them out, because they are us.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.