Why cramming 10 candidates on stage could work against the Democrats

- Share via

In October 1999, the Republican hopefuls for president gathered in New Hampshire to debate. That is, all but one — front-runner George W. Bush. Sen. Bob Dole also skipped a debate in early 1996, leaving his less prominent rivals to talk about him in his absence.

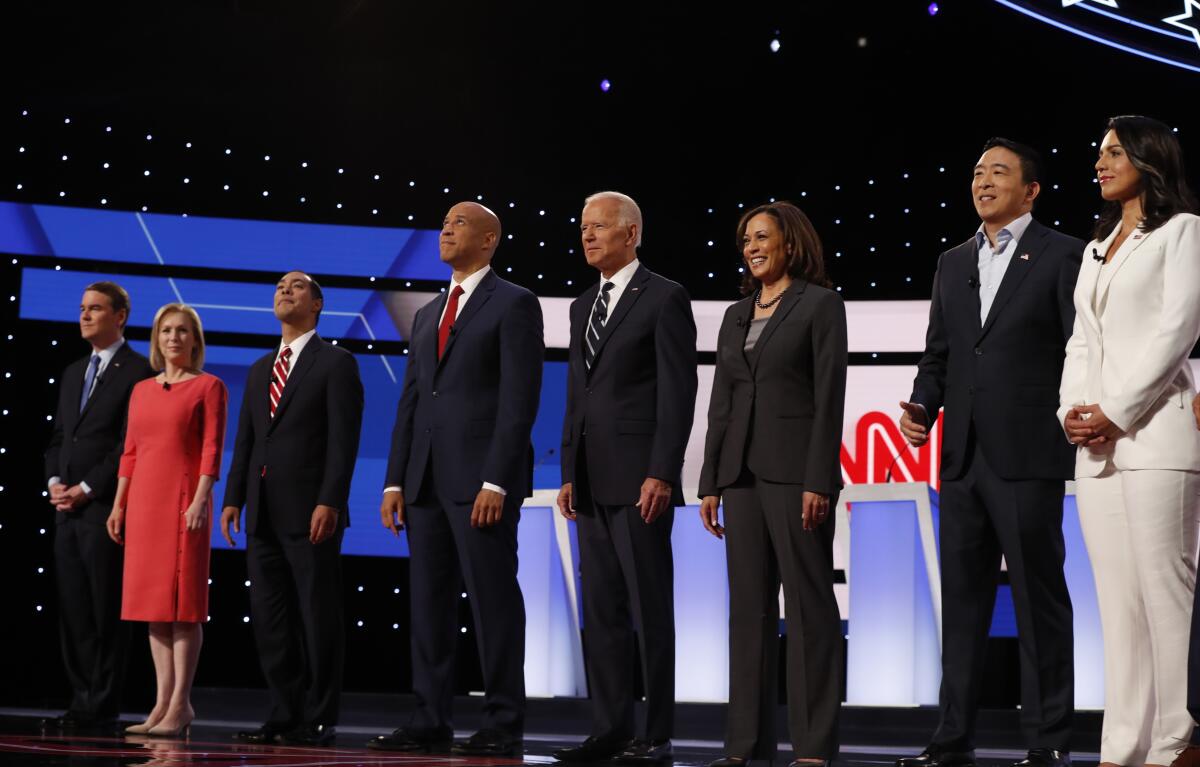

In 2019, it’s hard to imagine a candidate — even one running ahead in the polls — giving up a spot on the debate stage. Instead, some candidates have made qualifying for the debate part of their fundraising appeals. And even the ones who are contending for the top tier, like Joe Biden, Elizabeth Warren and Kamala Harris, have eagerly used their debate time to lay out their positions and attack their opponents.

While debates mostly look the same — a group of candidates standing behind podiums and answering questions from moderators — the politics around them have been transformed. There’s more demand for parties to be open and internally competitive, which has some advantages.

But it’s surprising and a little dismaying that the format has remained largely unchanged. The traditional format isn’t suited to helping the party pick among top-tier candidates, and it definitely can’t eliminate fringe ones. No one is ever happy with the rules for who gets included. And while debates do allow the public to see the candidates perform, they also can’t make voters feel better about their choices.

In just four years, nomination politics has shifted and the process is much less focused on winning elite support. In 2016, Hillary Clinton became the front-runner by clearing the field and cleaning up in the race for endorsements. You’ve probably figured out that this isn’t how 2020 is going. At all.

Instead, while a handful of candidates are leading the pack, they haven’t exactly scared off their competitors — or one another. So debates have become less about signaling to the “party establishment” — which might be the kiss of death — and more about courting small donors (necessary to qualify for the debates) and drawing in voters and activists who are engaged but undecided.

The media environment has changed as well. A big part of debates used to be a media narrative about who won and — well, mostly just about that. The availability of platforms like Twitter, along with lots of niche websites and blogs, means that voters are no longer dependent on a few networks to tell them what happened and why it mattered. In theory at least, this should be able to open up more discussion about which candidates performed well, and, perhaps more importantly, what the key issues were.

Polls indicate that Democrats are most concerned about electability this year, the main goal being to beat President Trump. But after Clinton’s surprising loss in 2016, it’s not clear exactly what the 2020 race will look like. This leaves the Democratic candidates with an interesting dilemma. They’re simultaneously posturing over who is the clearest alternative to Trump and who is the candidate who might beat him in a general election. These are two different things. They all want to look like tough general election opponents and emphasize how they will govern differently from Trump, but at least some of them also want to make the case that they can win Trump voters back.

When the primary system as we know it began in the 1970s, the process seemed like a pretty straightforward balance: Find a candidate who has the right positions to win the party nomination and comes off as genial, politically skilled and mainstream enough to win the general election. That might still be the basic calculus. But it’s no longer clear how to think about the general election under conditions of extreme partisan polarization: Is it a turnout battle, or a contest for swing voters in pivotal states? Both? Something else entirely?

After the first round of debates in June, there were questions about whether Kamala Harris, by bringing up Joe Biden’s record on race and busing, had reopened an issue that would alienate swing voters, or solidified her position as a standard-bearer for a new Democratic Party. (It’s not clear that either of these things happened.) Julián Castro took a stance on the protection of rights for transgender Americans. Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders doubled down on their economic plans. And candidates like Amy Klobuchar and Michael Bennet urged pragmatism and more moderate policies.

Primary debates allow the candidates to showcase their different approaches, but it’s not obvious that they really help voters decide among them. In fact, debates might just make the party’s voters more attached to their own preferred candidates and less willing to rally around the eventual nominee. If that’s the case, cramming 10 candidates up on stage could actually get in the way of the party’s most important goals: narrowing the field and creating a nomination process that even the losers can live with.

Julia Azari is an associate professor of political science at Marquette University.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.