The 10 words that could sink Trump’s presidency

- Share via

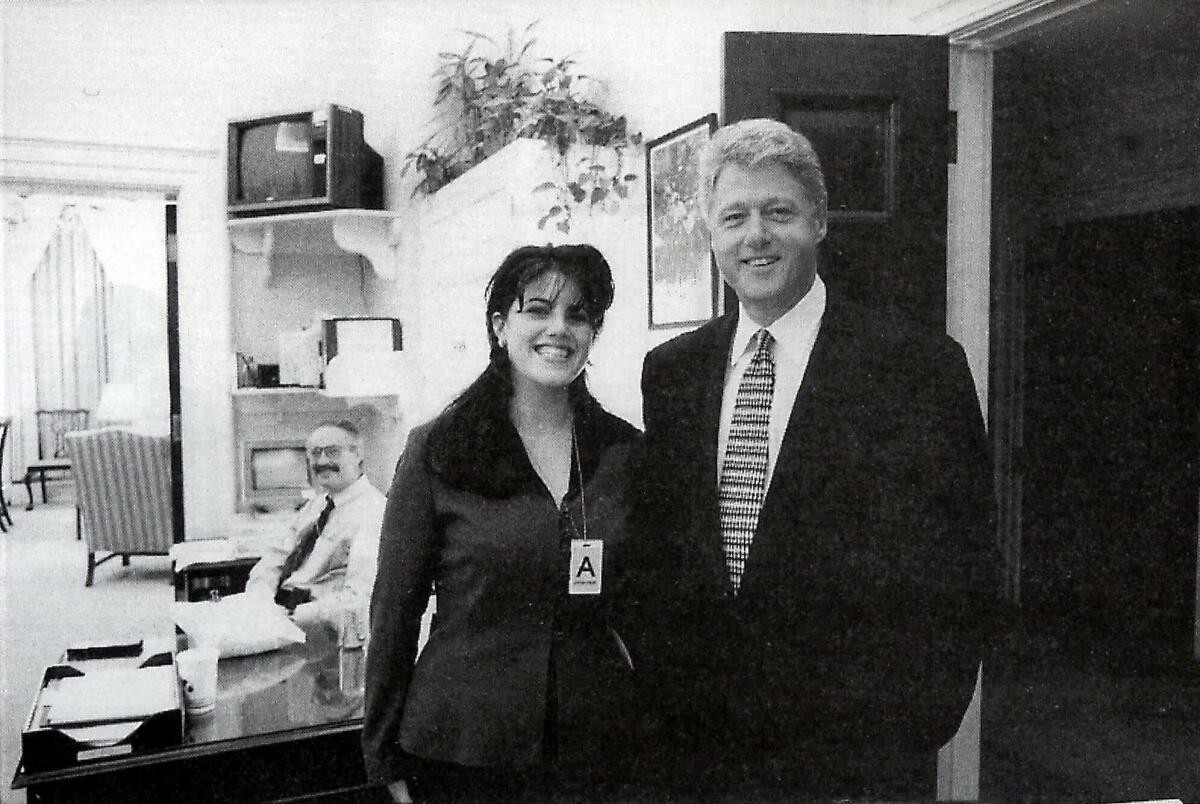

The course of a presidential investigation can sometimes hinge on a few words. For Bill Clinton, they were his assurances at a news conference that “I did not have sexual relations with that woman.”

For Richard Nixon the words were, “All right. Fine,” his agreement on the “smoking gun” tape to stop the FBI from investigating the Watergate break-in.

And Donald Trump’s fate may rest on 10 words from the rough transcript of his conversation with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky: “I would like you to do us a favor though.” We’ll be picking that sentence apart for a long time to come; by the time this is over, we’ll all know it by heart.

The main snag for Trump is that adverb, “though.” Attached to the end of a sentence, “though” restricts or qualifies what was said previously. And when what precedes that sentence is a promise or offer, “though” signals a condition: “You can take the car tomorrow. You’ll have to pick up the kids, though.”

That’s clearly the role “though” plays in the transcript. Zelensky says he’s ready to buy more missiles from the U.S.; Trump responds with “I would like you to do a favor, though.” If Trump hadn’t wanted to connect the missile purchases to the favor, he wouldn’t have used “though.” He would have started the sentence with something like, “Oh, and another thing.”

Then there’s the weird way Trump couches his request as a “favor.” That turns out to be just as much of a snag as “though” is. As a speech act, to ask for a favor is to request an act of personal kindness that benefits the requester: in this case, launching investigations that would benefit Trump rather than Ukraine. “Favor” is not the word you’d use to ask Ukraine to implement extensive structural reforms, as some Trump defenders have argued the president was doing. That would benefit Ukrainians rather than us. It would be like asking President Xi Jinping to do us a favor and hold free elections.

In any event, Zelensky had no choice in the matter. What Trump asked of Zelensky was a faux favor: a request made under the pretense that the addressee will fulfill it out of goodwill, when in fact rejecting it would come with a price. To many, Trump’s request for a faux favor evoked the language of “The Godfather,” a film in which the failure to grant a favor could have dire consequences. Calling it a “favor” follows a transparent fiction of the Godfather’s world, that when people defer to the don, it’s not out of fear or greed but respect. That’s implicit in the movie’s signature line, when Don Vito explains he is going to “make him an offer he can’t refuse.”

But the mobster analogy isn’t entirely apt. As leaders go, Trump is no Vito Corleone. His narcissism gets in the way. Asking for faux favors is endemic wherever there are asymmetries of wealth and power, particularly at higher altitudes, and the fiction isn’t always as transparent as it was to the don. Jennifer Chatman, a professor of management at UC Berkeley’s Haas School of Business, has studied the toxic effects on an organization of narcissistic leaders, particularly grandiose narcissists, who have an inflated sense of their intellect and allure and an unlimited appetite for praise. She points out that such a leader may think he’s flattering his underlings by asking for favors rather than issuing orders. In doing so, he “allows them to breathe his rarified air” and gives them the gift of choice. “Narcissists have a nose for patsies,” she observes, “ready to ingratiate at a moment’s notice.” It’s another kind of quid pro quo: Do as I ask and you can bathe in my luster.

That’s Trump to a T. He has boundless faith in his charisma. Long before he was president he was confident that his wealth and celebrity invested him with a glow that inclined others to want to please him and grant him favors of every kind (as he notoriously put it, “When you’re a star…”). The journalist Seth Hettena noted in the New York Times last year that “‘do me a favor’ is one of [Trump’s] favorite lines.”

From the start of their conversation, Zelensky lavished on Trump the ardent praise he expects from everyone in range of his aura. So it was natural for Trump to suppose that Zelensky would be gratified by a request that implied a personal connection and the promise of Trump’s gratitude. To Trump, all policy is personal, so he was surely pleased when Zelensky responded to his request for a faux favor by declaring Ukraine “open for any future cooperation” and raised the prospect of a future tête-à-tête and a ride in Trump’s plane.

Is it any wonder he came away from the call calling it “a perfect conversation?”

Geoffrey Nunberg, a linguist, is a professor in the School of Information at UC Berkeley and a regular contributor to NPR’s “Fresh Air.” His latest book is “Ascent of the A-Word.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.