Why American poultry — and Donald Trump — have loomed large in the Brexit debate

- Share via

America has loomed large in Britain’s Brexit debate. Or rather, Donald Trump and American poultry have.

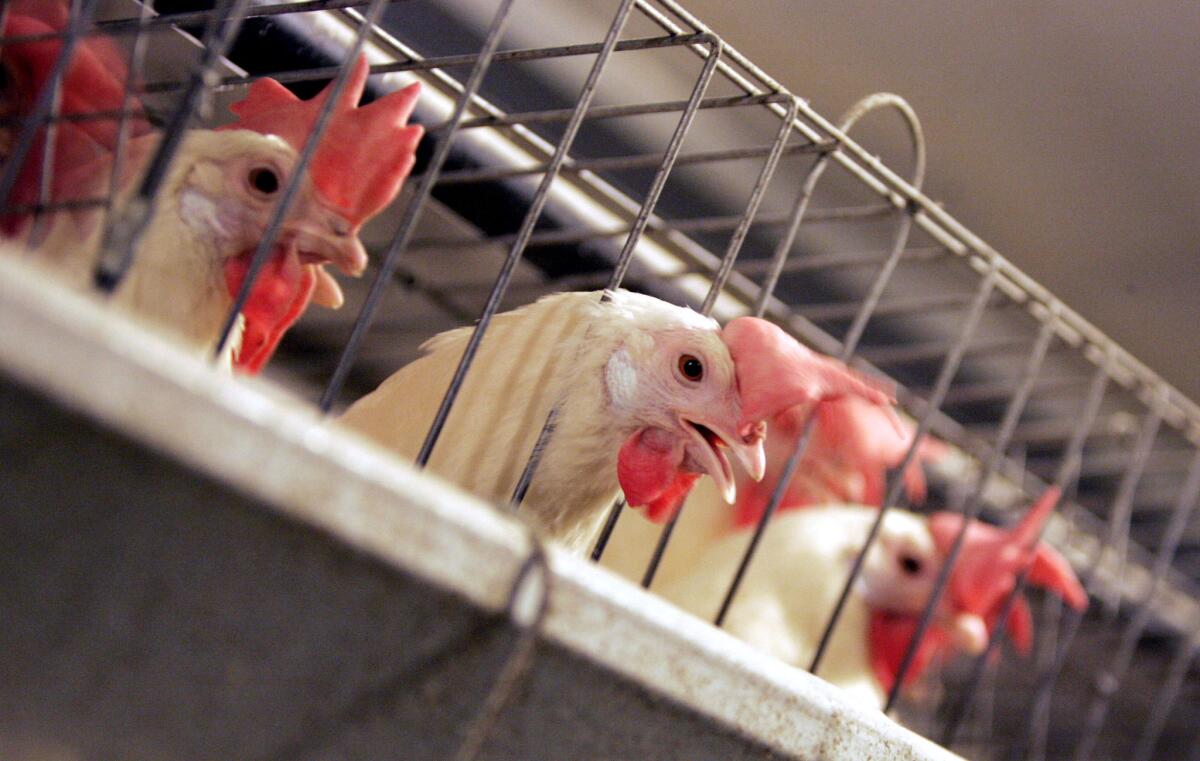

It would be an obvious overstatement to say that U.S. chicken — or even President Trump — is the reason consecutive prime ministers have been unable to manage a disobliging Parliament in efforts to leave the European Union. But no Brexit debate is complete without its chlorinated chicken moment.

The poultry issue is this: American processing plants dip their chickens in chlorinated water to kill pathogens, and they sell those chickens the world over — but not to any country in the EU. EU residents, including Brits, don’t like the idea of eating chlorine with their chickens.

So, as Britain contemplates a post-Brexit trade deal with the United States, one continuing cry of the anti-Brexit contingent, and not only the anti-Brexit contingent, is that we Brits do not want to choke down your foul (forgive the pun) chlorinated chicken. And if that weren’t bad enough, we’d have to negotiate the matter, as well as other points of a trade deal, with Donald Trump.

The Brexit debate is always peppered with other — you may think weightier — themes, of course: The need to honor the 2016 referendum result and preserve peace in Northern Ireland and protect the British economy.

Almost all the forecasts provided by reputable economists, including those in the U.K. Treasury, suggest that Britain would be considerably poorer if we leave the EU than if we remain in it — no matter what deal, if any, is finally approved.

Forecasts are, of course, imperfect, something the leading Brexiteers stress. The believe the predictions are based on a pessimistic, even defeatist, view of an insipid Britain unable to take advantage of the apparently marvelous opportunities that await when we are finally liberated from our current trade patterns shaped by our EU membership.

The Brexit cause holds as an article of absolute faith that, free from the “shackles” of the EU, we will strike trade deals that will more than make up for the new obstacles to our trading relationship with the EU — currently our largest trading partner by a long way.

This is, to put it mildly, a gamble. Above all we will certainly want, and need, a deal with the United States. During the referendum campaign, Barack Obama suggested that his administration would be in no hurry at all to sort out the fiendishly complex details of any such deal — a statement widely seen as trying to help the Remain cause. Donald Trump, strongly hostile to the EU as a multinational enterprise, has tried to suggest the reverse.

Trump’s enthusiasm may be necessary, but it is as much an embarrassment as it is helpful to the Brexit cause. In part, this is because of the widely held view throughout Europe that not only are U.S. poultry regulations unsatisfactory. Much of the entire American economic model is thought to be based on a harsh view of workers’ rights — not enough job security, not enough paid holiday, not enough guaranteed maternity and paternity leave.

But it is more than that. The United States is easier to attack now, in almost any argument, because of President Trump. Very few people who criticize the American version of a market economy have any detail at their command. Yes, it has long been the case that many European governments see the U.S. as too keen on deregulation and too unforgiving a society, but every suspicion is now given more potency by Trump.

Throughout the Brexit debate, Labor Party leader Jeremy Corbyn has claimed that the version of Brexit being pursued by the British government was based on following the U.S. “downhill” by diluting workers’ rights currently cemented by our membership of the EU. But Corbyn’s lifelong anti-Americanism is understood. He has, after all, spent decades blaming the United States for more or less everything — Cuba’s less than perfect human rights record, Venezuela’s chaos, ISIS, the Cold War.

What has been striking in the Brexit debate is that, when challenged by more moderate voices than Corbyn’s, no government minister — even those deeply hostile to the EU’s rules — chooses to make even a broadly positive case for the United States’ way of going about its business. If U.S. policies were precisely the same but some more orthodox figure occupied the White House, there would be less anxiety.

Johnson now effects a “close pals” relationship with Trump to add icing to the obligatory view for any British prime minister that we have “a special relationship.” But whatever he actually believes about worker rights — and he has said contradictory things — he dares not now say outright that he wants Britain to have an economic and social model closer to the United States’ than to the EU’s.

In any event, a British-U.S. trade deal will be very tricky and will probably take a long time to negotiate and ratify. That poultry issue will need sorting. But Trump’s advocacy is not going to warm many British hearts. Boris Johnson will need him to kickstart any deal — but Johnson will be holding his nose.

Mark Damazer, is the former master of St. Peter’s College, Oxford, and former head of BBC Radio 4. He is currently an honorary fellow at St. Peter’s and at Caius College, Cambridge.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.