State universities say they want diversity but recruit well-off, white, out-of-state students

- Share via

In 1996, I was a junior at Newton North High School in Newton, Mass., a wealthy Boston suburb. I was a lackluster B student who often lobbied to take lower-track classes to avoid the work. I had few extracurricular activities and did just OK on the SAT. So I was surprised to start receiving stacks of glossy college brochures. What did these schools see in me?

It took me 20 years to learn the answer: American higher education gives second chances to rich kids.

In college I became a serious student and now I’m an assistant professor of higher education. I study “enrollment management,” industry speak for how universities attract desirable students. The consultants I talk to — hired by universities to identify prospects — often mention “slugs.” That’s the derisive term for barely admissible prospects from “full-pay” households with incomes north of $200,000.

“They want us to find more slugs,” the consultants say. That’s what colleges saw in me as a high school student.

Last week, I published a report, with UCLA data scientist Crystal Han and in conjunction with the think tank Third Way, about the recruiting practices of public research universities. We based our analysis on a research project I started with Karina Salazar, who was my doctoral student when I was an assistant professor at the University of Arizona. Karina’s experience of college access differed from mine. She gave me permission to tell her story.

In 2007, Karina graduated third in her class at Sunnyside High School, in a low-income, predominantly Mexican and Mexican American community in Tucson, six miles from the UA campus. She had a GPA above 4.0, took every AP course offered and did well on the SAT. But she never received glossy college brochures, and no admissions officers visited Sunnyside — only military recruiters and the local community college. Despite the lack of guideposts, she found her way to the University of Arizona, but most of her college-going classmates attended a nearby community college, a decision that every major study shows reduces students’ chances of ever obtaining a bachelor’s degree.

The dominant explanations about inequality in college access generally blame students and K-12 schools for not being college-worthy — the infamous “achievement gap” — or they cite “undermatching,” the theory that high-achieving, low-income students fail to apply to good colleges because they get bad advice about what’s available to them. In turn, policy solutions focus on “fixing” students and high schools.

What if, Karina and I wondered, public university enrollment priorities are actually biased against poor communities and communities of color? If so, improved achievement and counseling would be unlikely to fix inequality in college access, or to achieve what the colleges claim to want — a racially and socioeconomically diverse student body. We decided to examine university recruiting, based on the idea that knowing which students are targeted would be a credible indicator of enrollment priorities.

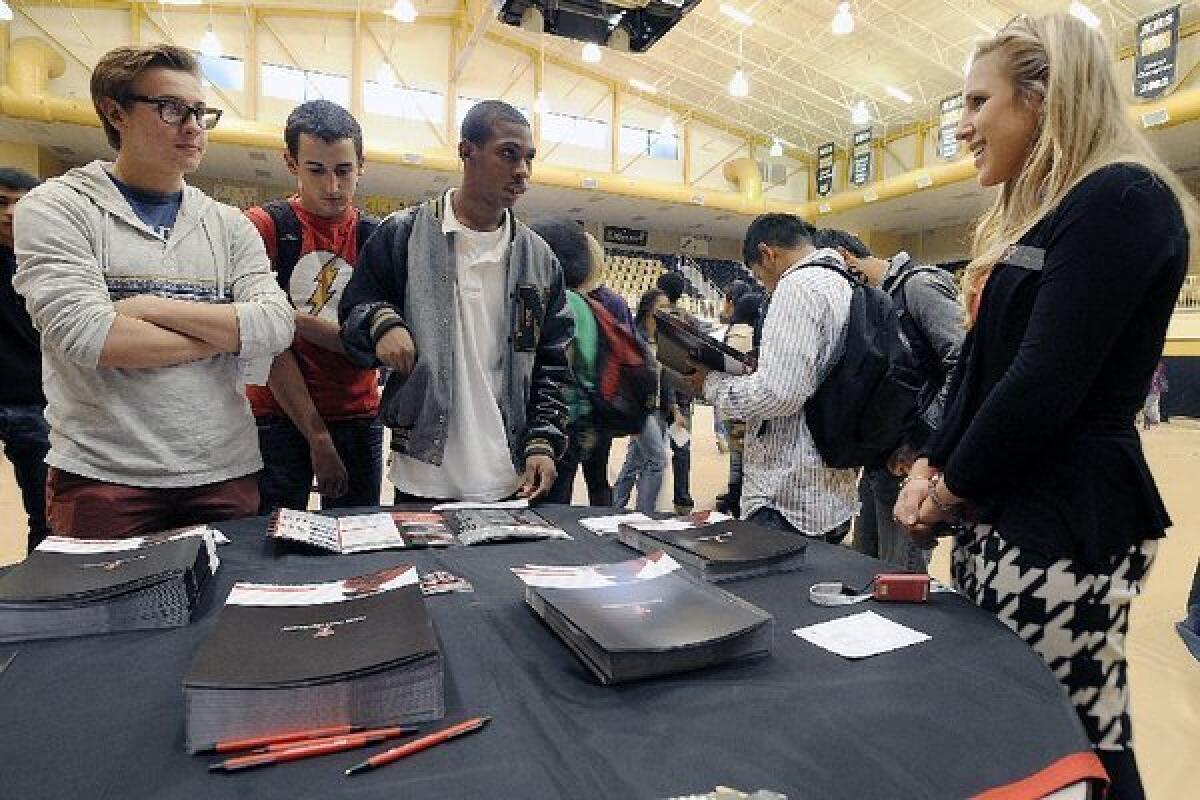

The Third Way report concentrates on one aspect of recruitment: visits by admissions officers to high schools, college fairs and other prospective student meet-and-greets. Twelve of the 15 public research universities in our study made more out-of-state than in-state visits. Seven made more than twice as many out-of-state visits. And the emphasis on out-of-state recruiting was on affluent public and private schools, and on predominantly white schools.

The in-state visits tracked in the report also emphasized relatively affluent communities, but to a much lesser degree than out-of-state visits. Further, in-state visits did not show that same strong evidence of racial bias that out-of-state visits showed. That is, the racial breakdown of the in-state schools visited by recruiters was similar to the schools they ignored.

(Two University of California campuses, Irvine and Berkeley, were in the sample. They were among the three schools that made more in-state recruitment visits than out of state, which comports with a cap the UC system was forced to put in place on out-of-state admits in 2017. )

Overall, the recruitment data underscore a fundamentally broken system for funding higher education, as well as ongoing racial biases.

First, funding: The decline in state support for public universities is well documented. The Pell Institute for the Study of Opportunity recently calculated a 50% decrease in such support since 1981, and earlier research I conducted shows that in response, universities dramatically increased out-of-state enrollment.

The Third Way findings, in turn, show that out-of-state students — both slugs and achievers — aren’t showing up at these schools out of the blue. Universities are devoting substantial resources to recruiting them. And such recruitment was strongest at the schools with the least state support (for example, the University of Colorado Boulder and the University of Alabama). The reasons seem clear: Nonresident tuition is often two to three times higher than resident tuition at public universities.

The bias toward recruiting at white high schools is harder to explain. Nevertheless, the data are clear: Out-of-state recruitment is concentrated at white affluent schools rather than nonwhite affluent schools.

Although out-of-state recruitment isn’t only about slugs, it also isn’t primarily about merit. When schools scour the nation for kids who can pay the full nonresident tuition, slugs (like me) look good. When they ignore high-achieving, poor students and students of color in their own backyards, they systematically funnel too many to community colleges rather than university.

Karina’s story has a happy ending. She is now an assistant professor of education at the University of Arizona. In July 2019, Karina defended her dissertation, based on our research project, at Sunnyside High School, with school district administrators and UA leadership and faculty in attendance. It helped galvanize local change that many others had been demanding. The president of the university made increasing enrollment from Sunnyside School District a priority, including hiring a counselor dedicated to local admissions. That September, UA recruiters made a surprise visit to Sunnyside, where 135 seniors received acceptance letters.

I’m happy the University of Arizona is finally looking for talented students on Tucson’s south side. But many public universities continue to ignore schools like Sunnyside. They are too busy looking for B students in wealthy Boston suburbs.

This is the real admissions scandal in American higher education.

Ozan Jaquette is an assistant professor at the UCLA Graduate School of Education and Information Studies. The data on university recruitment he developed with Karina Salazar is available online.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.