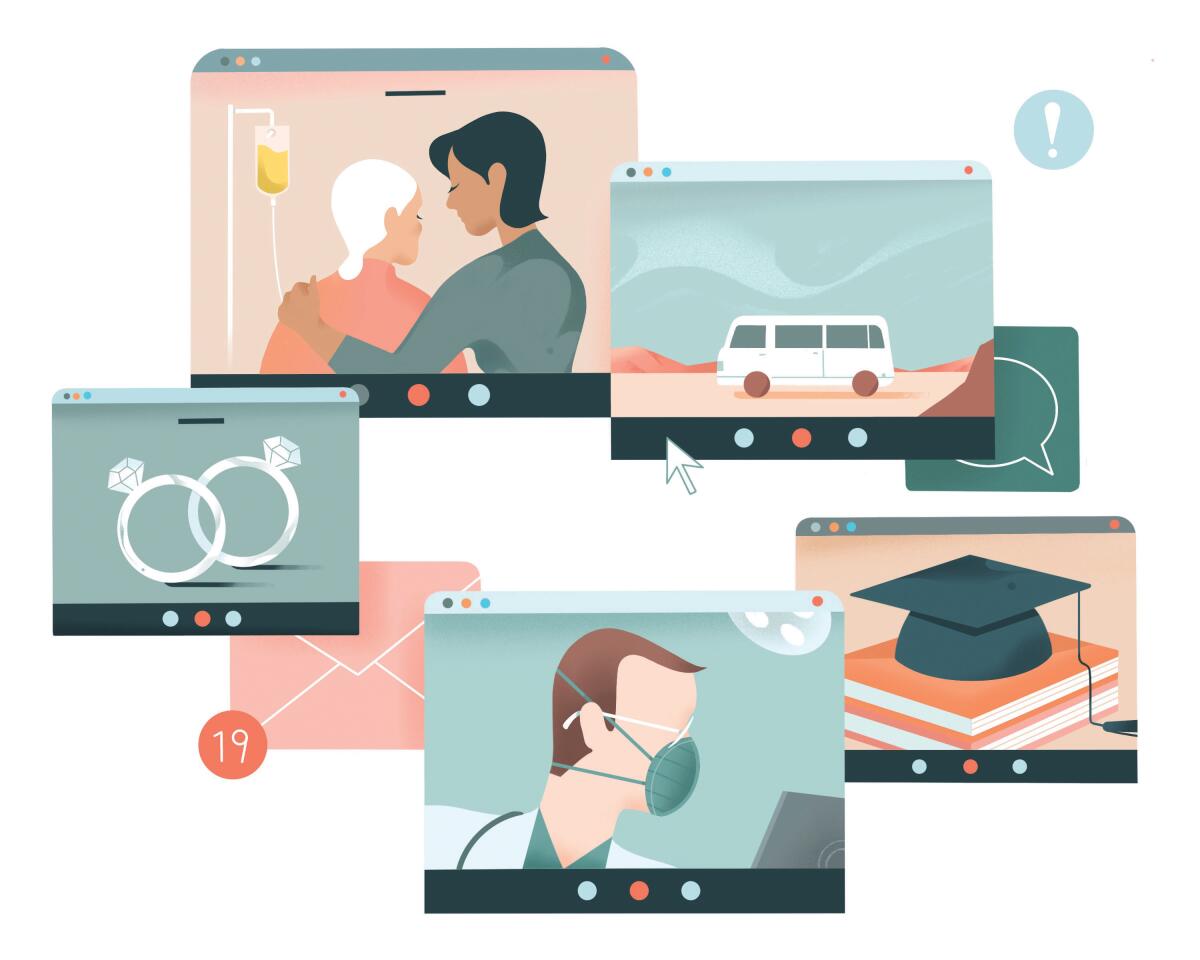

Dispatches from the pandemic: Love on hold, fragile parents and reluctant heroism

- Share via

Wedding postponed

By Ben Houston

I was supposed to get married yesterday.

I was supposed to be cracking cold ones, watching March Madness while getting ready with my groomsmen and my brother Will, my best man for life.

I was supposed to be getting anxious right before the ceremony — just like my dad who had to bring out a paper bag and a shot of whiskey to calm his nerves before his wedding.

I was supposed to lose it when I saw Lauren at the end of the aisle.

Then “I” was supposed to become “we” and everyone would lose it.

Our kiss, our first dance, trying to steal a moment to eat at the reception, we were ready for it all.

We should have been twirling around to Whitney Houston in a friend’s backyard in Phoenix, me looking like Paul Newman in a navy suit and her like Joanne Woodward in a white gown I still haven’t seen.

Life had other plans.

Instead we are in our pajamas eating Girl Scout cookies, self-isolating in our apartment in Los Angeles along with the rest of the city.

We’re devastated and heartbroken but, at the same time, at peace, confident we made the right decision.

Those are the emotions that happen when you call off your wedding six days before the day — because of a vicious global pandemic.

Seriously, what the hell?

The run-up to our wedding ran parallel to the spread of COVID-19. First, several older guests dropped out. Then guests who worked in healthcare couldn’t get the time off. Then a bridesmaid was stuck in New York.

Every day, we worried more and more about the big day. Butterflies and joy gave way to travel bans and quarantines.

It was the toughest decision we’ve ever made. But as soon as we made it, we knew it was the right one.

We all have to make sacrifices to stop this deadly spread. We postponed the most important day in our lives and sacrificed hours of planning and thousands of dollars — but we did the right thing.

Our wedding will mean more than ever, when we can have it. When my new bride and I finally walk out on that dance floor, we will be able to bust the moves we’ve been practicing in isolation, and it will feel so good.

Love in a time of coronavirus, right?

Ben Houston is an advertising licensing director for a motion picture studio.

Protecting the vulnerable

By Mary Lou Fulton

The coronavirus crisis really hit home as I read media accounts of Italian doctors forced to play God in overwhelmed hospitals. Younger, healthier people with the virus received treatment — a bed, oxygen, respirators. Older people might just be left to die.

My mom is one of those people who could get written off. She’s 78 and on kidney dialysis that she performs nightly at home. Her immune system is shot, and it took her six months to recover from a terrible bout of shingles just two years ago.

So if she’s going to stay feisty and flirty and ready to play the slots when the casinos reopen, we can’t roll the dice.

I’ve told my mom it isn’t safe for her to leave her Boyle Heights home except for doctor appointments. A week ago, I quit my full-time job, intending to start a new chapter focused on writing and music making. Now my job is protecting us from the virus.

I’m mindful that any move I make could bring infection into her home, so I have new routines. When I’m out, I wear gloves and carry wipes to clean door handles and shopping carts. I get to the grocery store when it opens, hoping to avoid crowds. I’ve read that heat can kill the virus, so I toss my hoodie into the dryer before going into the house.

Once inside, I wash my hands and wipe down what I’ve touched — doorknobs, a light switch, my phone, the credit card I used at the store.

As each day brings more restrictions, I’m thinking ahead. Instead of waiting a few weeks for my mom’s next dialysis-supply delivery, I drove 90 minutes to the warehouse to pick up as many supplies as I could fit in my Kia Soul.

I take my mom’s temperature twice a day, and mine, too. So far, so good. But that could change, and if it does, my mom’s odds aren’t so good. I have Facebook friends who say they aren’t worried because if you’re younger than 50, there’s just a 1% chance the virus will kill you, based on Chinese data. For my mom and others in their 70s, it’s almost one in 10. For folks in their 80s, it’s 18%.

So I’m asking the young and healthy to think about the ripple effect of every choice they make. Stay home, keep your distance, reduce the spread of the virus so that hospitals will have the capacity to care for older people instead of pushing them aside. You can count on me to protect your mom. Will you help me protect mine?

Mary Lou Fulton is a writer, musician and former program officer at the California Endowment.

Hunkering down

By LaVonne Ellis

Back before everything turned upside down — when was that, last week? — I was happily van camping in the Arizona desert with my dog, Scout. This was after we had escaped from San Diego with two parking tickets and a quite rational fear of impoundment. A few years ago, I decided to live in my van so I could stretch my funds and travel. But San Diego and many other cities have made living in a vehicle illegal, and I’d already received a police warning on that front.

Since I am working on a book about the conflict between cities and van dwellers, heading to the desert to write in peace seemed the reasonable thing to do. Then I heard about an RV park for the homeless in Austin, Texas. I wanted to see it, maybe interview some of the inhabitants — you know, for research.

But by then, word was making the rounds about a highly contagious virus that started in China. I wondered: Should I worry? I wasn’t sure, but heading to a big city and meeting lots of people suddenly didn’t sound like such a good idea. I changed my mind about going a couple of times, embarrassed to be perceived as alarmist but also feeling increasingly alarmed.

After I embarked on my trip, the news on the radio got worse every day. There was a death up in Washington state and then more and more deaths. People in my over-70 age group were said to be more likely to die from the virus. The illness had a chilling name, COVID-19, and it sounded like it was spreading fast.

When I stopped to visit friends in a remote corner of eastern Arizona, I looked at a map and saw that my best friend Linda’s place, high in the mountains of northern New Mexico, wasn’t too far out of the way. Might as well pay her a visit.

The thing about best friends is that they’re always glad to see you. And this very special friend has a permanent welcome mat out for me. The closer I got to her place outside of Taos, the more I realized Austin could wait. And I could wait out this virus far from all the craziness, in a beautiful spot half a mile from the nearest neighbor and 30 miles from the nearest town. No one can call me homeless now.

LaVonne Ellis is a former correspondent for ABC Radio News.

College interrupted

By Remi Godinez

Rumors that we would be sent home started flying on Tuesday morning. The official news broke in an email around 5 p.m.: All undergraduates would have to leave campus by the following Tuesday, and classes would move online for the rest of the semester. “For students poised to graduate: Please pack as if you will not return to MIT for classes.”

Minutes after the message arrived, the seven seniors in my mechanical engineering seminar sat at a table in the lab with Danny, our professor, all trying to grasp the idea that this was how our senior year would end.

Our seminar was making a windlass, a kind of winch used to raise an anchor. Ours was made according to an 1899 diagram from the renowned Herreshoff boat builders. Sitting in the seminar with my senior year suddenly in shambles, I knew that if I only had one week left at MIT, I wanted to spend it machining. And looking at the faces around the table, I could see my classmates felt the same way.

The mood at our seminar, the determination to make the most of this last week — sand-casting bronze, machining parts, putting teeth in aluminum gears — was echoed by a lot of the seniors I talked to over the next couple of days. MIT can be brutally challenging and demoralizing at times. There’s a campus expression that students often invoke: IHTFP — which translates, in one version, as “I hate this frigging place.” But what sustains us is what got us there in the first place: our passion for the work we do. We wanted to keep doing what we love with the people we cared about until the bitter end.

The initial high spirits and resolve of that first night faded quickly as we all tried to grasp the ramifications of leaving midsemester. It was easy to say that we’d finish our courses online, but chemistry labs and advanced manufacturing courses don’t lend themselves to virtual classrooms. And for some students, the news was devastating. One roommate’s family told her not to come home because of the risk to her pregnant sister and aged relatives, so instead she was planning on holing up alone in Maine. Some lacked access to fast internet in their family homes and wondered how they’d be able to join even a semblance of class. I was with my friend Miguel when he learned he couldn’t go home to El Salvador because he’d have to quarantine for 30 days upon arrival.

My college experience ended two months early. I’ll always be a mechanical engineer who makes things, and I know that I’ll stay in touch with my closest friends. But I’m sad about leaving all the people that make MIT the intense, passionate community it is. It’s the unrealized potential in relationships with people on the gymnastics team, my lab partner who’d teased that one of his friends was interested in me, or the friends with a small “f” that I’d wanted to have lunch with before I was done that make leaving so hard.

During orientation, every MIT freshman receives a list of 101 things to do before you graduate. No. 101 on the list is “Understand the true meaning of IHTFP.” Taking stock of everything I’ve lost, both academically and socially, the deeper meaning of the phrase is suddenly so clear — I have truly found paradise.

Remi Godinez is hunkered down in Los Angeles.

Facing risk

By Eric Snoey

I am a 60-year-old ER doc. How do I balance caring for my patients and myself?

Dr. Roberto Stella, a 67-year-old Italian physician, died of COVID-19 on March 10. He had insisted on treating patients even after protective gear ran out. “We don’t stop. We are careful, and we go on,” he was quoted as saying. His colleagues heralded him as a hero.

It’s a romantic image: The selfless doctor stalwart against an indiscriminate virus, much like a soldier carrying a wounded comrade or a firefighter rushing into a burning building.

The analogy, while flattering, is wrong and dangerous for doctors. Police, firefighters and soldiers knowingly put their lives at risk when they raise their hand for that work. Very few physicians are wired that way. What we do may look like courageous improvisation amid catastrophe, but it’s scripted, routinized for everyone’s safety and enormously dependent on hospital resources.

All of us in the emergency room are fervently committed to our lifesaving roles. But if being an ER doc means the routine potential of catching a lethal disease, many of us will reconsider our early choices.

This is exactly the situation I find myself in.

The chaotic environment of a county hospital ER or intensive care unit presents a real risk of contamination with the mysterious, transmissible coronavirus. Patients line up at our front entrance with every kind of medical problem; they are medically complex, often non-English speaking, sometimes homeless. To sort COVID-19 from the scores of other possible diagnoses means interfacing in the most intimate way with each of them.

It’s hard to do this perfectly and safely even in the best of circumstances, and we are in far from the best of circumstances. In my ER, we ration coronavirus tests — no more than 10 a day for 200 patients. Masks are recycled, provided they weren’t “touched.” I assess patients from the doorway of the exam room, the medical equivalent of social distancing. Is that cough, that fever coronavirus? Or just the flu, asthma, heart disease?

At my age, if I get the virus, I have 3.6% chance of dying from it — about the same as for some forms of heart attack or coronary bypass surgery. COVID-19 has already killed dozens of doctors; hundreds more have become ill. Two ER docs, in Seattle and New Jersey, are in critical condition because of their exposure to the coronavirus; two more have tested positive in Illinois. I pray the U.S. doesn’t become like Italy, where the virus has so overwhelmed the healthcare system that infected patients over 65 were simply refused treatment.

My colleagues respond to all this with quiet resignation; resolute, if still anxious. We understand how treating ever growing numbers of infected patients could sweep us down a path to where, like Dr. Stella, we cross a threshold.

A 60-year-old colleague tells me she assumes she will get the virus and survive. I’m not that sanguine. Perhaps supplies will get replenished, the tests will become common, containment will help. It can’t happen soon enough.

Dr. Eric Snoey is vice chair of emergency medicine at Highland Hospital in Oakland.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.