Schools are at least as important as shopping malls. Keep what’s open, open

- Share via

With COVID-19 infection and hospitalization rates surging, the ongoing effort to reopen more classrooms has been stymied. Nonetheless, California public schools that have opened successfully can and should stay that way, while readying themselves in case things turn sour.

That includes the very small program that Los Angeles Unified School District was running for about 4,000 of its students with the greatest needs, which unfortunately is being closed for now, Supt. Austin Beutner announced Monday.

It’s easy to understand why Beutner is nervous about the rising rates in Los Angeles County. They’re much higher than in New York City, where classes remain open. But if the situation is safe enough for shopping — and most stores are allowed to remain open — then it should be safe enough for schools, where conditions are more tightly designed for the protection of both students and staff. The new orders by Gov. Gavin Newsom say that schools that are physically open can remain that way.

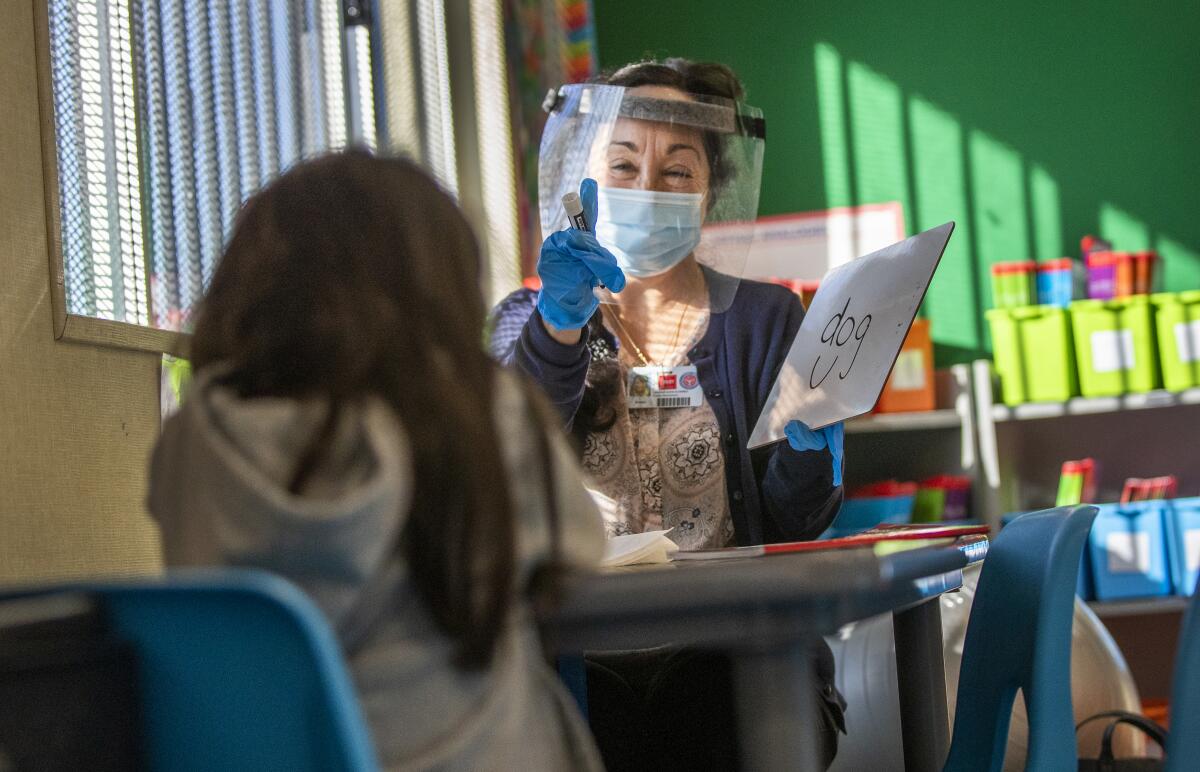

The small LAUSD program has been running safely. It’s to Beutner’s credit that a careful system of testing and tracing is in place — which he’s planning for all schools and students once they can return. There are no known cases of disease transmission among the students, who represent less than 1% of L.A. Unified’s population.

It’s also a particularly important educational undertaking, providing services for students with disabilities and those in need of tutoring. Dedicated staff volunteered to work with them in person. In other words, these are the students most in need of help, whose parents want them there and whose educators are willing to join them.

Much to everyone’s surprise, school reopening generally appears to be a safe undertaking, even when COVID-19 infection rates are rising. European experts concluded that schools were not a serious factor in spiraling rates there this fall; most have remained open. There haven’t been reports of major outbreaks involving deaths or hospitalizations in the United States, even though many schools have opened.

This is anecdotal evidence rather than proof of safety, to be sure. No one has yet given schools a clear signal based on actual study, telling them when it’s safe to reopen, to what extent and under what conditions. But we’ve also learned a lot since the early days of the pandemic, when everything from beaches to child-care centers were closed. Schools that have opened with clear, safety-oriented rules have done well, especially with elementary students, who appear less likely to become sickened or transmit the infection.

School leaders also should consider this truth: There’s no real evidence that reopening schools is dangerous. And though this isn’t the time to start major expansions of in-person schooling, there’s reason to think that those already operating safely can continue doing so.

We’re never going to be guaranteed absolute safety at schools, certainly not before most of the U.S. population has been vaccinated. Rather, the decision to reopen or not is one of continual risk management. There will be some additional cases of the coronavirus as a result of large-scale school reopenings. But there are other dangers associated with the schools remaining closed. People who drop out of high school, for example, have a significantly shorter lifespan than those who take a diploma. They too often live in the kind of poverty that has put many Americans at higher risk of death from COVID-19 as well.

Reopened districts would obviously need to watch the situation even more closely than they already do. They should prepare families for the possibility of another closure, and act quickly at early signs that the higher COVID-19 infection rates could be dangerous to teachers, students or families.

But existing in-person education should remain open, as long as the signs look good. Without the commitment to keeping the most vulnerable, high-poverty and disabled students in school, the state’s current situation will worsen: Students in middle-class areas, where COVID-19 rates have often been low enough to allow some classrooms to reopen, will continue getting at least a partly normal education while low-income students will learn remotely. No matter how much money is poured into schools with disadvantaged students, the gaps between them and more well-off students will continue to grow as long as they can’t go to school.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.