Here’s one way to hold Trump accountable for the insurrection: Sue him

- Share via

President Trump promised, accurately, that his Jan. 6 “Save America/Stop the Steal” protest would be “wild.” As it turns out, its wildness created litigation opportunities that would otherwise be impossible.

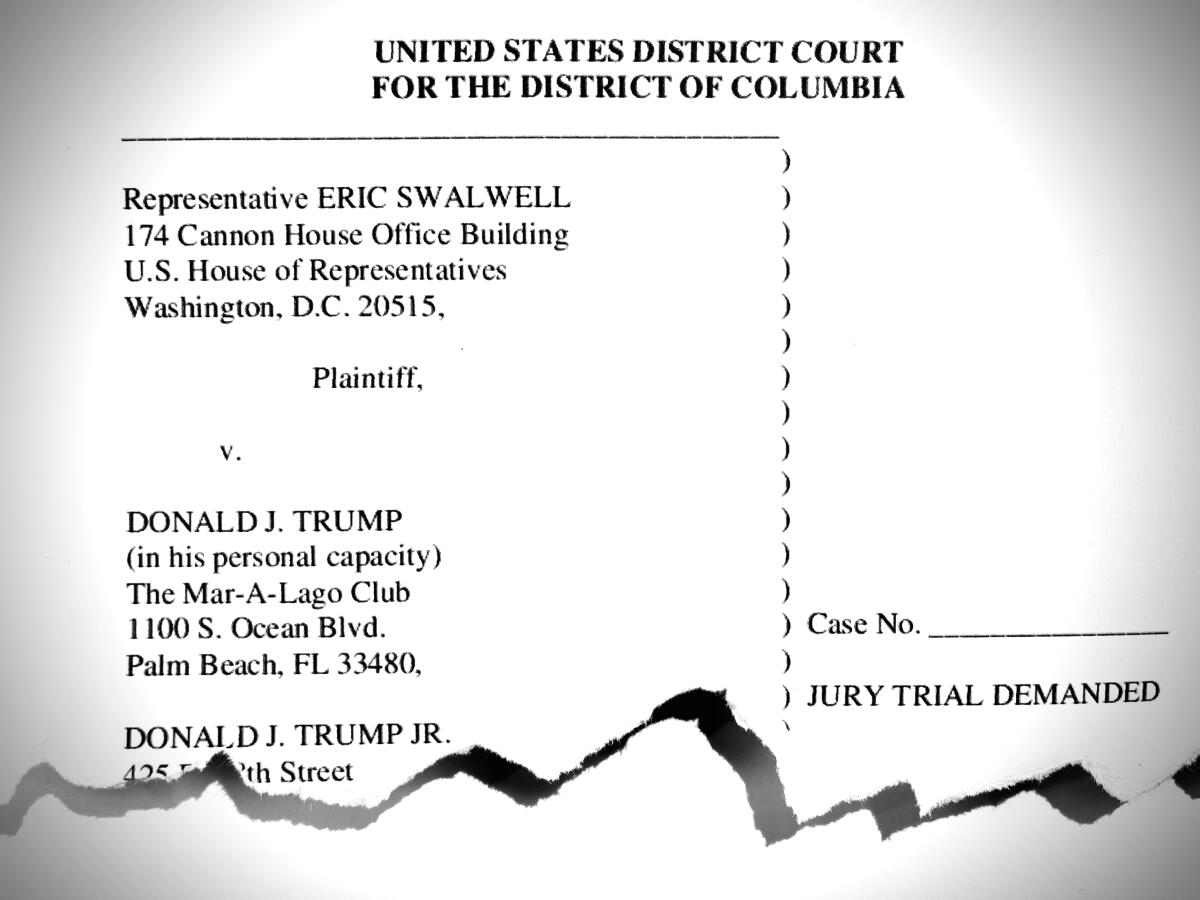

Two sitting members of Congress — Rep. Bennie Thompson (D-Miss.) and California Rep. Eric Swalwell (D-Dublin) — have each filed lawsuits against the former president (and others), in the wake of the attempted insurrection. These are civil suits — legal actions between private citizens or entities that are brought to reimburse the plaintiff for damages caused by the defendant.

The two congressmen allege Trump’s lies about the 2020 election incited the Capitol attackers and intentionally harmed them. But their goal goes beyond a dollar payday. Swalwell and Thompson hope to hold the former president accountable in a way that he has maddeningly eluded to date.

The path to accountability is through the legal terrain known as discovery. In civil cases, the U.S. court system allows both sides to demand vast troves of information from each other, essentially any evidence that is relevant or could lead to relevant evidence. Most importantly for the two Jan. 6 lawsuits, the parties can be required to give depositions — sworn testimony under penalty of perjury.

Anyone paying attention to the Trump presidency knows that a deposition to Donald Trump is like a cross to a vampire. He can’t seem to tell the truth for more than a few minutes at a time. He stonewalls on questions he wants to evade. But in a civil case, the judge can order Trump to respond. If he remains intransigent, he could be ordered to jail until he complies.

That sort of power could unearth protest planning documents, emails among participants and witness testimony about exactly how the president reacted when he watched the Jan. 6 mob surging through the halls of Congress. Trump would have to raise his right hand and swear to tell the truth about what he knew and when he knew it concerning both the Capitol attack and his false claims of election fraud. Criminal evidence is sometimes turned up in civil discovery. And perjury could get the former president into deeper hot water.

First, however, Swalwell and Thompson’s lawsuits have to overcome hurdles that could get them tossed before discovery begins.

One obstacle is what’s called “standing.” In the last 35 years or so, the U.S. Supreme Court, at the instigation of conservative justices beginning with Justice Antonin Scalia, has honed and strictly policed the doctrine of standing. Swalwell and Thompson may not sue Trump, let alone get anything out of him, just because they believe he lied or incited rioters. They must show what the court calls “a concrete, particularized injury in fact.”

Such a personal injury may be slight, but it must be concrete. And here is where Jan. 6’s wildness opens a door. As a mob broke through police lines into the Capitol, Swalwell and Thompson can make a case that they were terrified, physically under threat and impeded from doing their official duties — in particular, certifying the election results that put Joe Biden into the White House.

That may be fairly thin stuff as harm or injury goes, but as the judge overseeing both cases makes a decision on the issue, it could well suffice.

There is another hurdle between Swalwell and Thompson and the holy grail of discovery and a Trump deposition. The cases must survive defendants’ motions to dismiss. Typically, that means the court has to conclude before the case goes forward that if the allegations in the plaintiffs’ complaints are true (the main question to be decided in an actual trial), the plaintiffs would be legally entitled to relief.

Here again, Jan. 6 creates a legal opportunity. There is a specific law on the books — 42 USC 1985(1) — which allows “an action for recovery of damages” against anyone conspiring to “prevent by force, intimidation or threat” an official from discharging his duties.

Trump’s lawyers will no doubt argue against any such a conspiracy on the grounds that the former president didn’t intend for his followers to violently storm the Capitol. They’ll claim he genuinely believed the election was stolen, so he lacked the knowledge that stopping the certification process was improper. But a civil plaintiff can “allege generally” states of mind such as intent and knowledge. On that standard, Swalwell and Thompson’s complaints are likely to pass muster.

Will the plaintiffs prevail in the end? Will Trump and his co-defendants (in Swalwell’s case, Rudolph Giuliani, Donald Trump Jr. and Alabama Republican Rep. Mo Brooks; in Thompson’s case, Giuliani, the Proud Boys and the Oath Keepers) be made to pay? Only a trial can tell.

Win or lose, however, the unprecedented events of Jan. 6, combined with every citizen’s right to seek damages for concrete injuries, could force a public reckoning: the former president sworn to tell the truth, answering questions about his role in the Capitol siege and the months-long attempt to overthrow a free and fair election.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.