Republican tactics to suppress the Black vote echo those seen after the Civil War

- Share via

On election day, Nov. 7, Americans will vote for thousands of candidates for public offices — governors, state officials and legislators, mayors, a multitude of county and town supervisors. Their elections will be run by an army of poll workers, many of them citizen volunteers who receive only token payment for their efforts.

They will open the polls, check voter lists, monitor voting machines and count votes. These unsung jobs embody the machinery of democracy in action, where political partisanship meets the hard reality of numbers. To work, this machinery depends on the trust of the American public, if republican government is to survive.

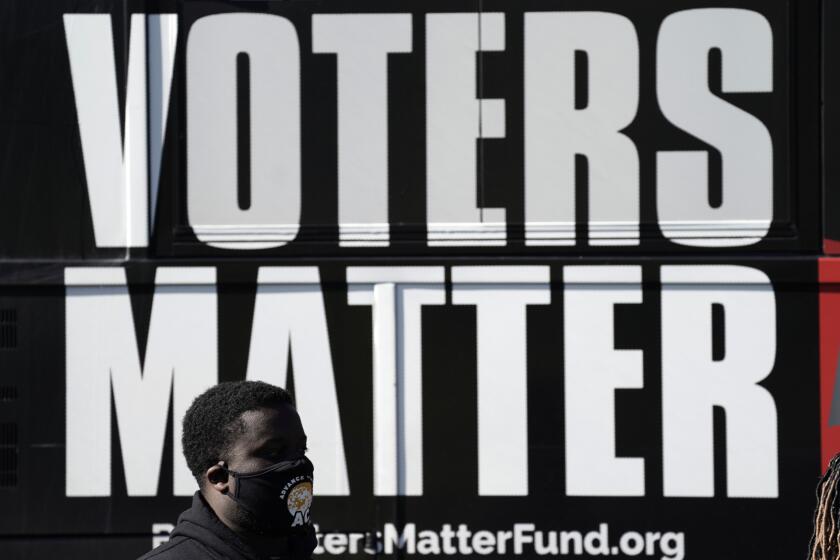

Every year Republican leaders enact more laws and rules that make it increasingly difficult for Black and other minority voters to cast ballots in the South.

In recent years, we have seen right-wing activists abetted by demagogic mainstream politicians fuel baseless and ultimately subversive theories of widespread election fraud. Two-thirds of Republicans still believe that the 2020 election was stolen from Donald Trump. Such suspicion has spread to infect even local contests and the most benign election practices. In 2022, no fewer than one-third of election workers reported that they knew at least one person who quit because of fears and threats.

The systematic assault on elections has begun to recall the most politically fraught period in our history, the post-Civil War Reconstruction Era of the 1860s and 1870s.

Voting is essential in any democracy. So is memory. That’s why many states that enact restrictive voting rules also embrace book bans to suppress history and ideas.

The raw violence of that era was far worse than we see today. White supremacist Democrats knew that the fragile Republican Party’s survival in the South depended on Black voters, who would have to be scared away from the polls if the Democrats were to prevail.

Thousands of newly enfranchised Black Americans and their white allies were threatened, beaten and murdered by the Ku Klux Klan simply for daring to attempt to vote in the former Confederate states. Registrars were menaced while they were making out certificates. White mobs physically pushed Black voters away from the ballot boxes. In some localities, Black voters were herded to the polls by armed men and forced to vote Democratic. In some counties, constables were too frightened to guard the polls. In Savannah, Ga., local police shot and killed several Black people and drove the rest away from the polls.

In scores of counties, the Republican vote was simply erased.

Despite such dangers, astonishing numbers of determined Black voters continued to flock to the polls enabling the Republicans to retain their majorities in Congress. Had it not been for the hundreds of thousands of Black Southerners who cast their ballots for Ulysses S. Grant, he would have lost the elections of 1868 and 1872, and Reconstruction would have come to an abrupt halt.

Before the Civil War, most Americans saw guns as primarily tools for hunting and pest control, not something to keep households safe.

By 1872, the worst violence was over. But new forms of voter suppression replaced overt terrorism as white supremacists steadily regained control of the Southern states. The Supreme Court ruled in a series of decisions that the enforcement of civil rights lay with the states, not the federal government, effectively crippling the 14th Amendment’s guarantees of equal protection. From the 1880s on, literacy tests and other forms of discrimination methodically subverted Black voting, and by the 20th century almost no Black Southerners were voting at all.

In our own day, the plot to kidnap Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer and the Jan. 6, 2021, insurrection at the U.S. Capitol showed the climate of violence that increasingly infuses our political culture. The most immediate threat, however, may be the subtler assaults on the process of elections.

Death threats against ordinary election workers have become commonplace. In some states, local vigilantes claiming to be freelance “election monitors” have sought to intimidate both voters and poll workers. In the wake of the 2020 election, self-appointed “cyber sleuths” in several states were permitted access to county voting machines in their partisan effort to find evidence of widespread fraud that supposedly prevented Donald Trump from winning re-election. Frivolous lawsuits have targeted poll workers with limited means, forcing them to defend themselves.

Other sinister trends are also at work. The systematic spread of disinformation from extremist right-wing sources continues to undermine public trust in voting and democratic institutions. False rumors of fraud remain epidemic in the right-wing ecosphere.

In the 1960s, said Douglas, Ga., Mayor Pro Tem Olivia Coley-Pearson, officials created impossible “tests” at the polls to prevent Black people from voting. “Where we are [now] is a more sophisticated means of voter suppression,” she said. “We are currently moving backwards.” Coley-Pearson herself has been charged with crimes twice for trying to help inexperienced voters cast their ballots.

In many states, Republican legislatures have arbitrarily restricted mail-in balloting, curtailed the number of days for voting, barred same-day registration and aggressively purged voter rolls, all measures that are likely to have the greatest impact on minority voters. Just in the last few weeks, Virginia removed 3,500 legal voters from its rolls. In October, Republican lawmakers in North Carolina forced through a law that could ultimately allow the GOP-controlled State Assembly to decide contested elections.

Forceful and consistent action by federal and — where possible — state authorities as well as nonpartisan citizens’ groups is essential if we are not to let our democracy slip through our fingers.

The Department of Justice must move quickly to use its existing powers to counter the intimidation of poll workers and racial discrimination against voters. More public resources must be devoted to the safety of election workers.

More trust in the election system must be established through better civics education at all ages. Former elected officials from both parties should be enlisted to support and explain election administration to build public trust. More work is also needed at every level to combat election-related disinformation and baseless conspiracy theories.

Bipartisan citizens’ groups should demand independent redistricting commissions and work to halt partisan purges of voter rolls, racial gerrymandering and restrictions on easy access to polls and early voting. They should also be prepared to sue governments that refuse to act to protect the democratic process.

These are challenging goals. But they are not impossible ones. The urgent lesson to be drawn from Reconstruction is that rights can be snatched away by partisan forces bent on eroding democracy. Passivity in the face of subversion is not a policy.

Fergus M. Bordewich is the author of “Klan War: Ulysses S. Grant and the Battle to Save Reconstruction.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.