Essential Politics: The left-right split is far bigger in the U.S. than in Europe — and it’s growing

- Share via

WASHINGTON — This is the May 7, 2021, edition of the Essential Politics newsletter. Like what you’re reading? Sign up to get it in your inbox three times a week.

Anyone who has watched U.S. politics in recent years knows that a widening gap between left and right, Democrat and Republican, has defined our era. Hardly a week passes without fresh evidence.

Americans — and some Europeans — have often talked of similar divisions in Western Europe’s major democracies. Divisive issues like Brexit in the U.K. and the rights of religious minorities in France drive comparisons to U.S. polarization.

But the U.S. differs notably from those other countries: Our ideological gaps are much wider on big cultural issues, according to a major new study by the Pew Research Center.

Get our L.A. Times Politics newsletter

The latest news, analysis and insights from our politics team.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

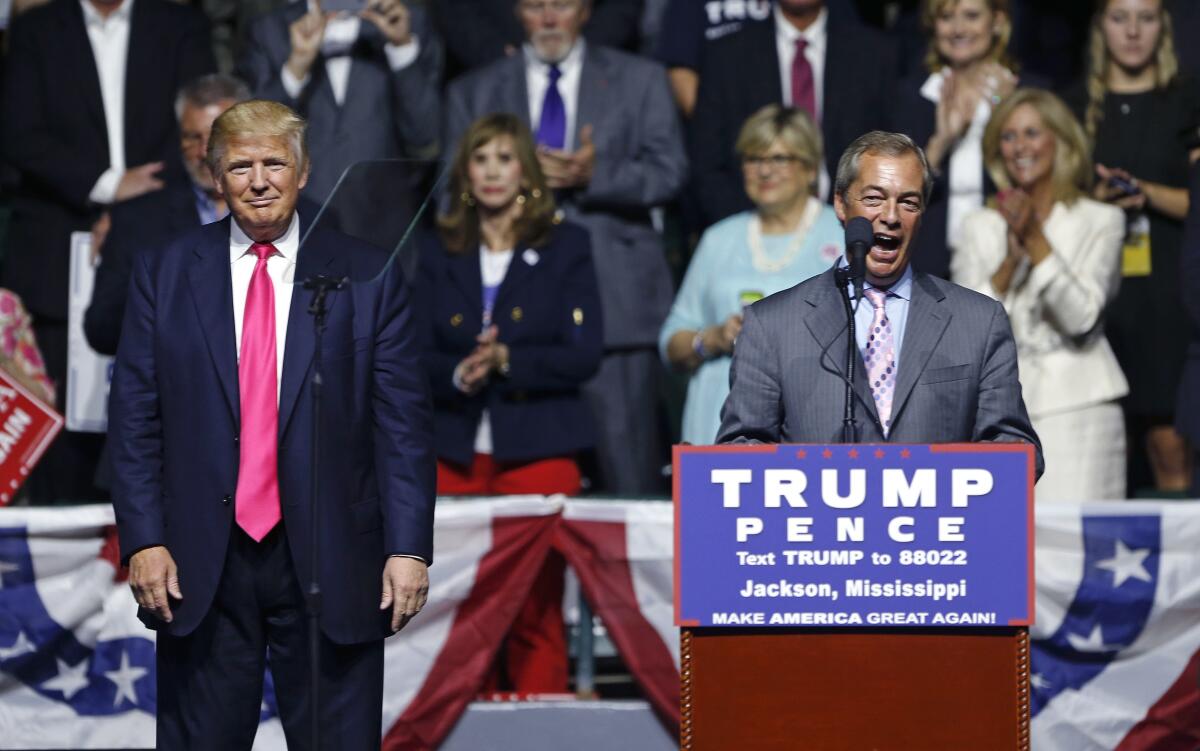

Pew began to study the comparison during Britain’s divisive debate over leaving the European Union and the campaign leading up to Donald Trump’s election as president. Researchers “really wanted to see what the concepts of nationalism and cosmopolitanism mean in the modern era,” said Pew’s Laura Silver, one of the lead authors.

What they found provides insights into America’s divides and how those differ from other wealthy democracies. The numbers, based on surveys of more than 4,000 adults in the U.S., France, Germany and the U.K., provide important context for understanding the Republican Party’s continuing evolution away from the country’s business establishment and toward becoming a more populist party of the right.

Questions of national identity

On several big issues, the center of gravity among conservatives in the U.S. stands further to the right than it does among their ideological counterparts in Europe, Pew’s numbers show. On the other end of the spectrum, liberals in the U.S. have moved further to the left in the past four years.

A large share of U.S. conservatives support restrictionist views of national identity, such as believing that “truly belonging” requires being native born or being a Christian. A large number also believe that discrimination against minority groups is an exaggerated problem.

Since 2016, across all four countries surveyed, the public has shifted toward less restrictive stands on issues of national identity. In Europe, that shift took place across the ideological spectrum. In the U.S., it did not.

U.S. liberals moved left — in some cases further left than their European counterparts. U.S. conservatives, however, started off further to the right than Europeans and did not move.

“Generally, we saw gaps closing in Europe,” said Silver. “The gap didn’t close comparably in the U.S.”

In 2016, for example, majorities in both the U.S. and the U.K., and about half of those surveyed in France, said that to be “truly” a member of their societies, it was at least somewhat important to be native born. About a third of Germans held the same view.

Now, the share holding that view has dropped a lot in all four countries — to about 1 in 3 in the U.S., U.K. and France and 1 in 4 in Germany. Each of the national surveys has a margin of error of about four percentage points.

In the three European countries, the drop did not vary much by ideology. In the U.S., liberals shifted much more than conservatives, so the U.S. divide widened.

Pew also asked if being Christian was an important part of being “truly American” or British, French or German. The share saying yes declined in all four countries. So has the share saying that to truly belong, a person must observe the country’s customs and traditions.

As with the question about native birth, however, in the U.S., the overall decline has been accompanied by a widening ideological gap. On the question of following national customs, the share of self-identified liberals and moderates calling it an important part if being truly American declined about 20 points. The share of conservatives did not budge.

Responses on a fourth topic — language — underscored the unique nature of the U.S. divide.

In the three European countries, close to 9 in 10 people across the board say being able to speak the dominant language is at least somewhat important to belonging. That’s also true of about 9 in 10 American conservatives.

But among American liberals, that view has declined sharply over the past four years: Just over half now say that speaking English is at least somewhat important for belonging in the U.S.

On that question it’s American liberals who stand out as different from their European counterparts; on others, U.S. conservatives stand out.

About a third of U.S. conservatives, for example, say that being native born is an important part of belonging; in the three European countries, no more than 1 in 4 say that.

Asked which is the bigger problem, people not recognizing discrimination where it does exist or people seeing discrimination where it does not exist, majorities in Britain, Germany and the U.S. said failure to recognize discrimination is the bigger problem. In France, the public closely splits on that issue.

In all four countries, a gap separates left and right on that question, with conservatives more likely to say the bigger problem is claiming discrimination where it doesn’t exist. In the U.S., however, the ideological gap is twice as large as in the U.K. or France and four times larger than in Germany.

Similarly, the ideological split in the U.S. is about twice as large as in any of the three European countries when people are asked if their country would be better off if it “sticks to its traditions and way of life” versus being” open to changes regarding its traditions and way of life.”

Religion is one of the factors that contributes to the larger ideological gap in the U.S. America remains more religious than most European societies, and white Christians, in particular, have become a mainstay for Republicans.

“Christians stand out on many issues from non-Christians,” Silver noted. “They are more likely to say there is a great deal of discrimination against Christians in their society and to say that being Christian is essential to truly being part of their country’s citizenry than non-Christians. They are also more likely to say other key factors — including speaking the language and being born in the country — are essential components of national belonging.”

Not only are Christians a larger share of the population in the U.S., American Christians are more likely than European ones to identify as being on the right politically, Silver said; 52% of U.S. Christians did so, compared with 48% in France, 36% in the U.K. and 27% in Germany.

The positions taken by a large share of U.S. conservatives put them in line with European supporters of right-wing, populist parties such as the National Front in France and the nationalist Alternative for Germany, the survey found.

That, in turn, helps explain the continuing strength of the populist faction of the GOP. Trump benefited from the rise of populism in the party, but as the Pew survey helps make clear, he didn’t invent it, and it’s not likely to dissipate whenever he departs from the political scene.

The GOP makes its choices

Liz Cheney or Elise Stefanik? Tradition or Trump? Two congresswomen personify the choice for the GOP, Janet Hook writes. As early as next week, Republicans in the House seem likely to vote to kick Cheney out of her leadership position because of her refusal to repeat former President Trump’s lies about winning the 2020 election and replace the Wyoming congresswoman with Stefanik, a relative newcomer from upstate New York, who has a less conservative voting record than Cheney, but has toed the line on support of Trump.

The move will be a “ratification” of the “Trumpification of the Republican Party,” lamented Bill Kristol, the conservative writer and editor and one-time Republican strategist.

Meantime, Texas Republicans are the latest to push legislation to restrict voting, which is straining GOP ties with business, Melanie Mason and Molly Hennessy-Fiske report.

The Texas GOP won big in a recent special election for a vacant congressional seat — Democrats got shut out of the runoff. Democrats were disappointed; should they be worried? Mark Barabak asks.

Enjoying this newsletter? Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

Immigration politics

Vice President Kamala Harris meets virtually with Mexico’s president about migrant issues, Noah Bierman writes.

Tyrone Beason travels the border for a personal essay on America struggling to live up to its promise as migrants seek refuge.

The latest from Washington

Conservative anger at Big Tech has pushed the GOP into Bernie Sanders’ corner on antitrust legislation, Evan Halper writes.

And the decision by Facebook’s advisory board to uphold the ban on Trump is further angering conservatives as it constitutes a major political blow to the former president — at least for now, Hook writes.

The Biden administration announced support for waiving intellectual property rules on vaccines, but there’s still a long road to get doses available to people in poor countries, Emily Baumgaertner reports.

Biden made a rare trip to a red state, delivering a pitch for his infrastructure plan in Louisiana, Chris Megerian wrote. He wants to sell Louisiana a new bridge — and much more

The administration is looking to triple the amount of protected land in the U.S., Anna Phillips and Rosanna Xia reported. The U.S. currently protects about 10% of its land area. The administration wants to boost that to 30%, to slow global warming, provide more habitat for threatened species and offer more recreational activities for Americans. But the details remain vague.

Black moms are more likely to die in childbirth than white moms. Sarah Wire looks at whether Congress will do anything about it.

A federal judge knocked down the CDC’s eviction moratorium. Erin Logan looks at what that means as the administration prepares to appeal.

Secretary of State Antony Blinken traveled to Ukraine and sent a warning to Russia, Tracy Wilkinson and David Cloud reported.

The April jobs report showed job growth slowing sharply and unemployment ticking upward. That’s a disappointing sign of a possible slowdown, Don Lee wrote.

And Doyle McManus noted in his column that every president eventually faces a major crisis. What will Biden’s be?

The latest from California

Caitlyn Jenner is trying to shift from the OMG moment to a true campaign for California governor. It’s not been easy, Maria La Ganga writes after an interview with the candidate.

Jenner and the other candidates seeking to oust Gov. Gavin Newsom in the recall have one big problem, Phil Willon writes. California is reopening and COVID-19 is declining. That could sap the energy behind the recall effort.

And George Skelton looks at Newsom’s proposal to ban fracking of oil and gas wells. The move is in part a political show driven by the recall, but it’s also a milestone in the state’s history, he writes.

A federal appeals court upheld California’s program for workers without retirement benefits, Maura Dolan writes. It was a major victory for a state law that many see as a possible national model.

Stay in touch

Keep up with breaking news on our Politics page. And are you following us on Twitter at @latimespolitics?

Did someone forward you this? Sign up here to get Essential Politics in your inbox.

Until next time, send your comments, suggestions and news tips to politics@latimes.com.

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.