The fate of California newspapers could be sealed in coming months. Do ‘carnage’ and ‘catastrophe’ await?

- Share via

Good morning and welcome to the L.A. Times Politics newsletter. I am Shelby Grad, deputy managing editor for news, filling in for David Lauter today.

You're reading the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Anita Chabria and David Lauter bring insights into legislation, politics and policy from California and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

A do-or-die moment for California newspapers

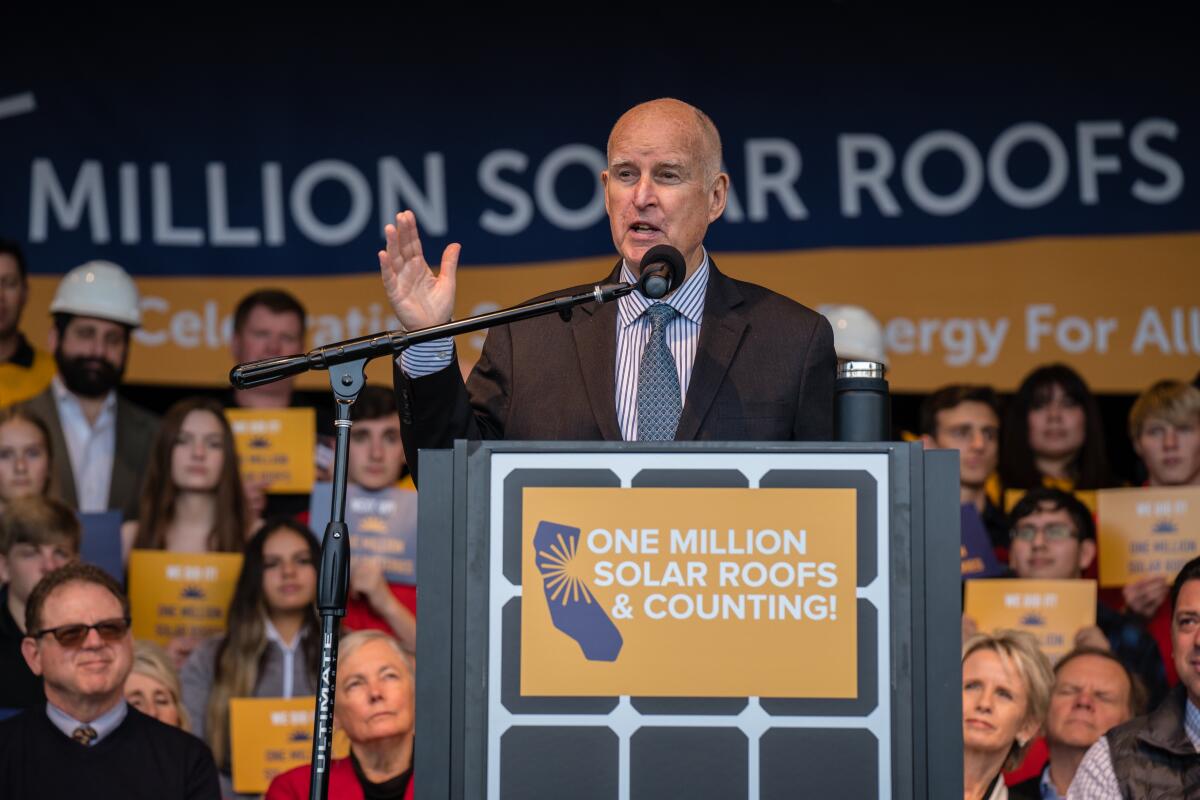

Jerry Brown was often ahead of the game in seeing where California was going.

But there is one insight that seems particularly worth considering this week as the forces of technology and commerce are squeezing vital California institutions like never before.

As governor, Brown urged the University of California Regents to embrace the leading edge of technology as they transformed education — and he used the newspaper industry as a cautionary tale.

Brown recalled “walking through newsrooms of the once powerful California newspaper empires. … There were rows and rows of empty desks,” Miriam Pawel wrote in her book “The Browns of California.”

That was well over a decade ago. If he visited today, Brown wouldn’t even recognize many newsrooms. Some have closed. Others have taken on the grim distinction “ghost newspaper.” Many have experienced wrenching cuts, with more likely on the way.

The work of journalism is more important than ever in a world where democracy is under threat, corruption bubbles in local government and society faces sharp divisions. Yet there are fewer boots on the ground seemingly every week.

This summer is shaping up to be a pivotal moment for what remains of the newspaper industry — and it would not be an exaggeration to call it do-or-die as publishers are pitted against the mighty forces that technology giants have been building for decades.

Here is what is at stake:

AI arrives

Artificial intelligence has long been considered a serious but vague threat to the bread-and-butter of journalism, with news and service stories that a computer might eventually be able to spit out faster and a lot cheaper. Now, we are seeing it in action. Google announced changes in search that offer options from artificial intelligence.

The publishing industry is already raising alarm bells, saying this new approach will summarize journalists’ work without sending users to their websites (meaning news organizations will lose traffic and advertising revenue).

We still don’t know exactly how it will work out. But I did some searching using Google’s Gemini AI search tool, and it definitely offered fewer links to journalism websites and a lot more information that kept me on Google’s platform. News organizations are using words like “carnage” and “catastrophic” to describe the changes, saying they could lose massive numbers of users.

Everyone in the news business is scrambling. Some are making deals with AI firms, essentially seeking payment to have their content used. Others are suing, arguing that these AI results are stealing from them.

One last lifeline?

California is leading the U.S. charge in asking Google and other platforms to pay for the news that is provided. The idea is for publishers to get a cut of the bonanza of ads the tech giants are pulling in. The main proposal is AB 886, which passed the Assembly but is awaiting a Senate vote. Among the things the bill addresses:

- Requires large platforms to pay news outlets for their products

- Set fees from arbitration

- Requires news outfits to spend at least 70% of the money on reporters

- It is similar to news protection laws already on the books in Australia and Canada.

Times Sacramento columnist George Skelton handicaps things this way: “Key lawmakers have agreed to pass something this summer, but haven’t decided what. They’re trying to weave together legislation that would attain a difficult two-thirds legislative vote, be acceptable to the big platforms and gain Gov. Gavin Newsom’s signature. The governor has been mum.”

Publishers say the bill would be a lifeline and is long overdue (disclosure: the Los Angeles Times is backing AB886. Others are skeptical of such laws, question how well they are working elsewhere). But Google is pushing back hard. Last month, it announced the search engine would reduce access to some California news websites. This week, Google also “warned” nonprofit newsrooms that the passage of legislation in California would threaten funding it has provided them.

It’s still uncertain where this will end, but there is no question this is a critical moment for the news business — in California and beyond.

Newspapers are getting smaller. The revenue needed to cover the state is dwindling. The debate about who should pay for news is more unresolved than ever.

And in an industry always drenched in (and sometimes blinded by) nostalgia, it must be pointed out that determining who pays for the news was once much simpler. In “Man of Tomorrow,” another great book about Jerry Brown, Jim Newton describes Brown early in his unconventional political career.

“He would spot a newspaper on a colleague’s desk and walk away with it without thinking to ask.”

If you value journalism and a free press, you can’t just walk away now.

What else you should be reading

The must-read: Progessive DAs was a big political trend in California a few years ago. But it’s not looking so good now.

Three quick hits: UCLA’s Gene Block faces the music in Washington; Newsom faces backlash — from close friends; London Breed thinks universities can save downtown San Francisco.

The L.A. Times Special: “The so-called culture wars focus on removing rights from women and others, but at heart, the battle is over what it means to be a man.” —Anita Chabria.

Until next week,

Shelby Grad

—

Was this newsletter forwarded to you? Sign up here to get it in your inbox.

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.