Coronavirus Today: What the CDC’s new mask guidance means

- Share via

Good evening. I’m Karen Kaplan, and it’s Friday, Feb. 25. Here’s the latest on what’s happening with the coronavirus in California and beyond.

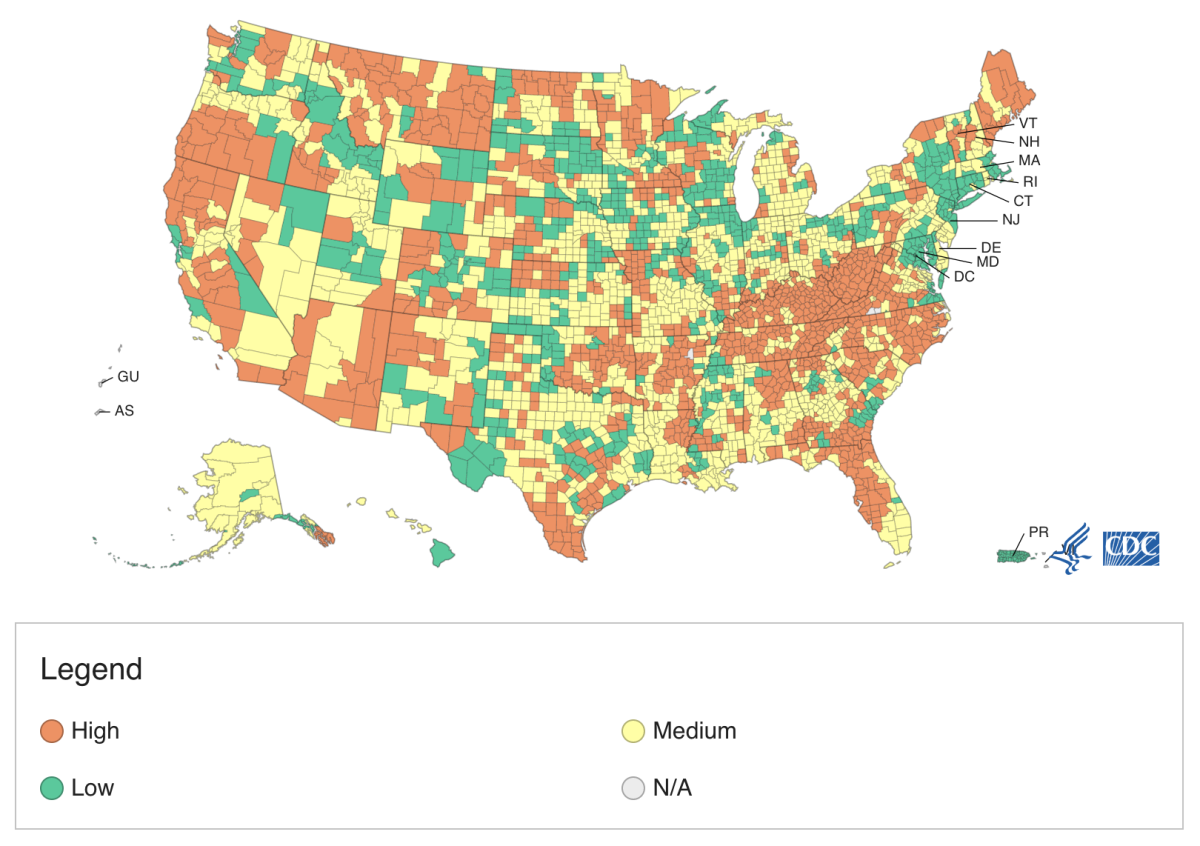

When you woke up this morning, 95% of counties in the United States had “substantial” or “high” levels of coronavirus transmission, according to the risk assessment system employed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Residents in all those counties were advised to wear masks while in indoor public places.

But as you read this now, 63% of counties are deemed safe enough by the CDC to make indoor masking optional. Those counties are home to 72% of Americans.

What accounts for this sudden and dramatic change? The federal health agency decided to scrap its old system for gauging a community’s COVID-19 risk.

It’s no longer based on the number of new coronavirus infections and the percentage of tests that come back positive. In the Omicron era, with the virus in heavy circulation but most patients experiencing mild illness, the old rules just didn’t make sense. (The rise in home testing also has complicated matters because negative results are rarely reported to health authorities, and the kits aren’t as accurate as PCR tests.)

The new paradigm focuses instead on whether local hospitals are in danger of being overwhelmed with severely ill COVID-19 patients. The CDC now computes “COVID-19 Community Levels” using a mix of hospital capacity and the number of COVID-19 patients already in them. Over time, other metrics will be added to the mix, including data from sources like wastewater surveillance networks.

“It’s clear that the country as a whole is transitioning from pandemic to a state in which the virus is endemic,” Dr. William Schaffner, an infectious-disease expert at Vanderbilt University, told my colleague Melissa Healy. “But we also have a very large country, and we’re not all doing it at the same pace. This lets the folks at the front of the line move a bit faster than those at back of the line.”

Most of the San Francisco Bay Area is at the front of the line, with community levels classified as “low” or “medium.” In Southern California, Orange, Ventura, Santa Barbara, Riverside and San Bernardino counties are all in the “medium” tier.

Los Angeles County, on the other hand, is classified as “high.” So are San Diego and Imperial counties, most of the San Joaquin Valley and the majority of California’s rural north. That means masks are still recommended indoors in all of those places.

But L.A. might not stay there for long. The nation’s most populous county is close to the border of the “medium” category and could make the transition as early as next week, my colleagues Luke Money and Rong-Gong Lin II report. In fact, they write, according to data on the CDC website, L.A.’s metrics may already be good enough to qualify for the upgrade.

Before the CDC unveiled its new system, county Public Health Director Barbara Ferrer signaled that she and her colleagues were in no rush to change L.A. County’s mask rules. After reviewing the new guidelines and seeing how they match up with local conditions, officials plan to present some options at Tuesday’s Board of Supervisors meeting.

After that, they’ll consult with business and labor groups. In all likelihood, that means a new masking plan won’t be ready until late next week at the earliest.

Looking across the country, much of New York, Massachusetts, Maryland, Illinois, Wisconsin and South Dakota are colored green on the CDC’s new map, indicating “low” COVID-19 risk. Oregon, Montana, Kentucky, West Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee, Florida and Maine all have broad swaths of orange, a sign that their hospital systems remain at risk of being overwhelmed with COVID-19 patients.

Schaffner said the CDC’s new approach was sensible, but he warned that the agency must prepare communities to dial up their public health measures if conditions worsen.

“Once we’ve flipped the switch to off, we need to remember there’s a big world out there, and if there’s a new variant, I’m afraid we may have to flip that switch back on,” he said. “That will be very hard. Most Americans want to put COVID in the rearview mirror.”

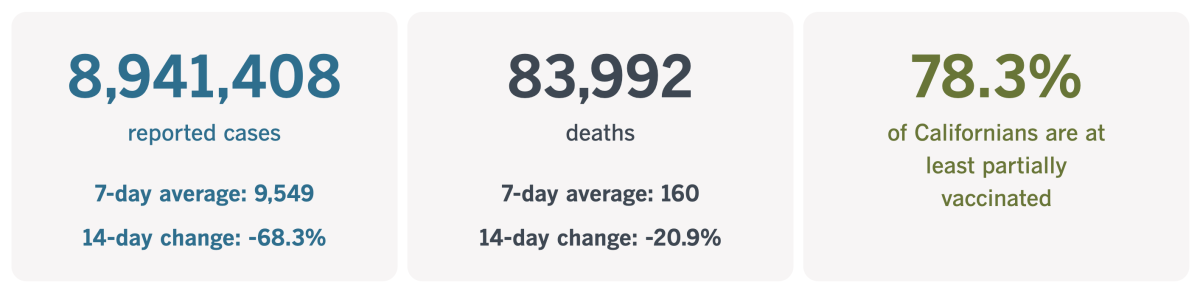

By the numbers

California cases and deaths as of 7:12 p.m. Feb. 25:

Track California’s coronavirus spread and vaccination efforts — including the latest numbers and how they break down — with our graphics.

As if a global pandemic weren’t enough ...

The Omicron wave is subsiding. Mask rules are softening. A post-pandemic future is coming into view.

And then the optimism brought on by that progress was swept away this week when Russia invaded Ukraine.

Even if you’re not a foreign policy aficionado, news of the military action on Wednesday was hard to miss. Especially when it prompted people to throw around terms like “World War III.”

Perhaps you had a reaction like that of Chris Giaco, the owner of a Long Beach bookstore called Page Against the Machine.

“It just feels like a constant stew of chaos,” he told my colleagues. “We can’t get space to think about things.”

Giaco used to hope the upheaval brought on by COVID-19 would result in a more balanced society with less emphasis on work and more time for everything else. That idealism didn’t last. In fact, he fears the pandemic has created a kind of instability that makes a march to war more difficult to stop.

For many people, the news from Ukraine — and the prospect that it could balloon into a larger conflict — was the last straw. After two years dominated by a public health emergency, a recession, toxic partisanship and more, there’s a distinct possibility that things are about to get even worse.

“As individuals, we may be able to cope with any one of these events,” said Lawrence Palinkas, a medical anthropologist at USC who studies mental health. “Having to cope with all of them simultaneously is proving to be overwhelming for many people.”

Susana Sanchez spent most of Wednesday night anxiously checking her phone for updates on Ukraine. She was already dealing with depression after falling ill with COVID-19 and nearly dying of pneumonia. On top of that, the pandemic cost her husband his job as a restaurant cook.

So when she woke up Thursday afraid that a world war was on the horizon, her body was literally shaking.

Portland, Ore., therapist Jeff Guenther understands why.

“Everything that has happened in the last couple of years is bringing all our powerlessness to the forefront,” he said.

Guenther assured his 822,000 followers on TikTok that if the news seemed overwhelming, they shouldn’t feel bad about tuning it out by exercising, watching a mindless show on Netflix or discussing the latest Wordle puzzle with friends.

“You’re powerless in so many ways, and the war in Ukraine is yet another devastating reminder of that,” he said. “But you have power over your daily routines, so feel that power and control.”

For some, that’s easier said than done.

Kitty Hall said she had been comforted by the possibility that the pandemic might be winding down. Now that comfort has been displaced by anxiety and depression as she contemplates whether the U.S. will send troops to Eastern Europe, whether the conflict will reach American soil and whether nuclear weapons will be deployed.

“I let my emotions run,” she said. “It’s something a lot of us have never experienced, ever.”

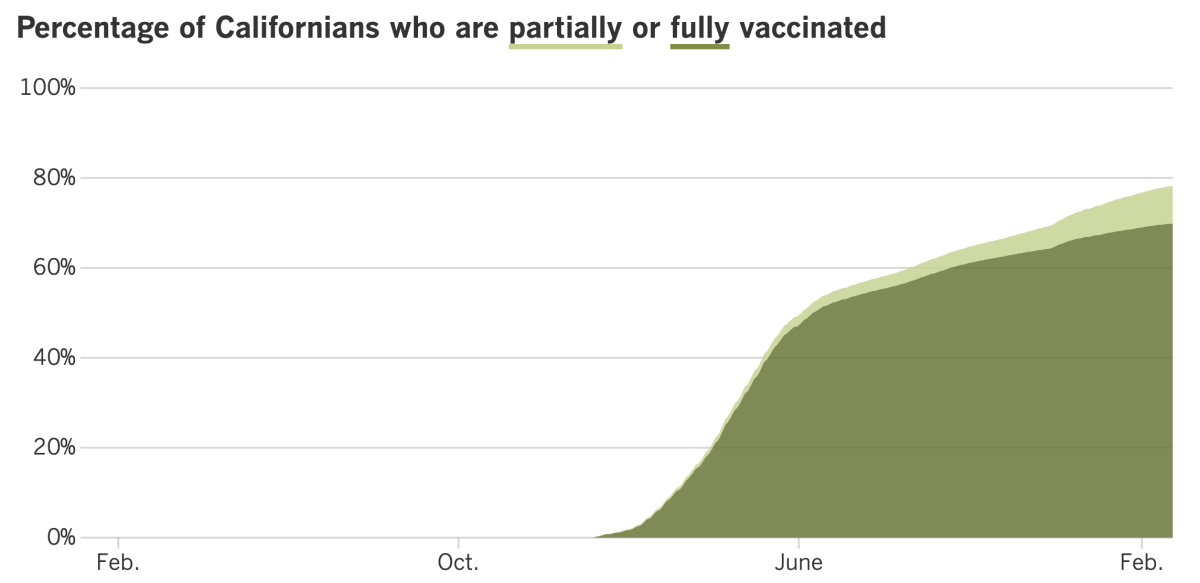

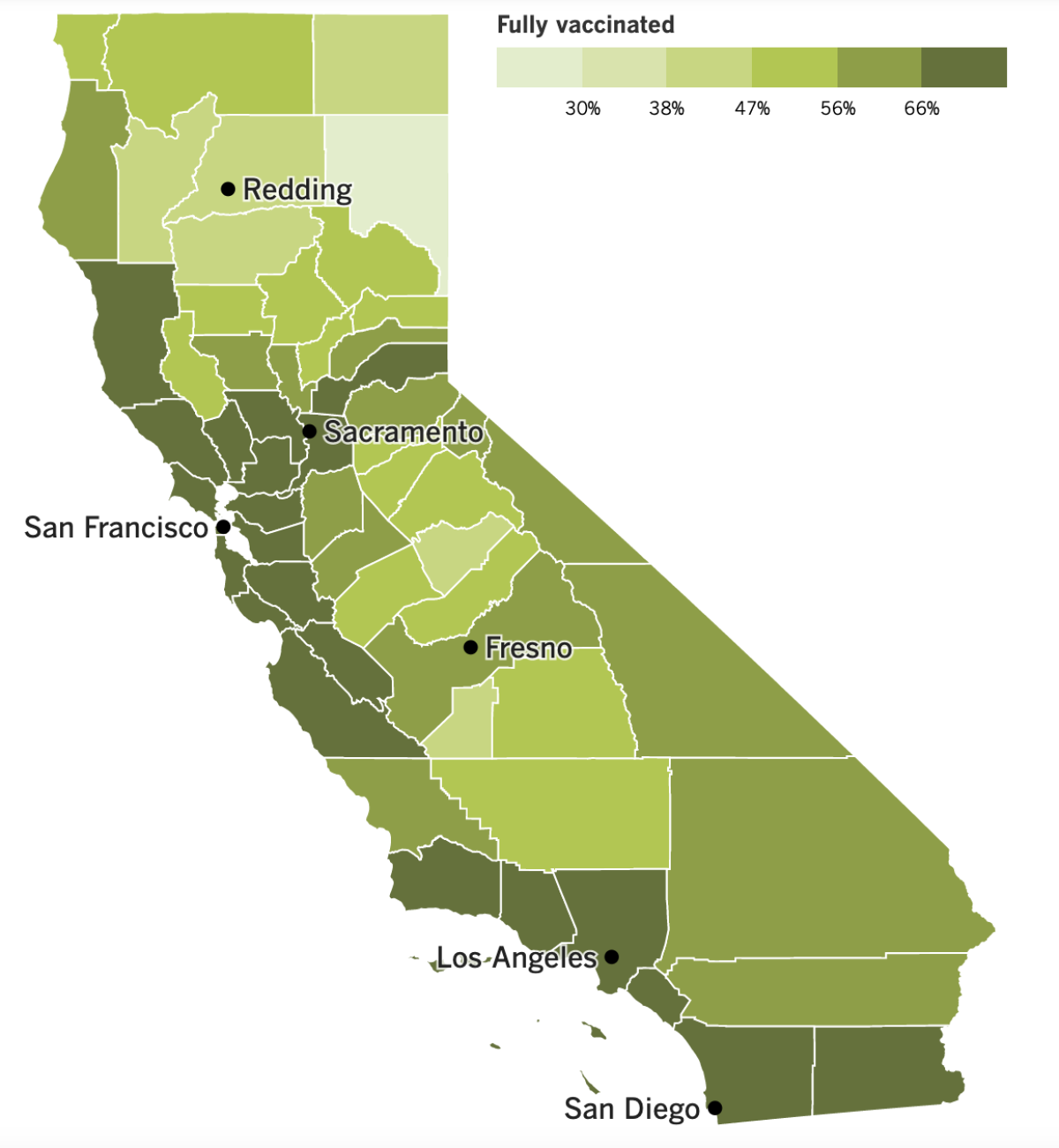

California’s vaccination progress

See the latest on California’s vaccination progress with our tracker.

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most.

In other news ...

Finally, pollsters have found something Californians can agree on: The quality of public education in the state took a significant hit during the pandemic.

A whopping 72% of voters who participated in a UC Berkeley Institute of Governmental Studies poll co-sponsored by the Los Angeles Times said educational quality had gotten worse “since the outbreak of the coronavirus.” That includes the 40% who said it had gotten much worse.

Only 21% of voters said they’d give public schools an A or a B; that’s down from 27% in 2011. At the same time, the percentage who would give schools a D or an F rose from 13% to 25%.

Eric Schickler, co-director of the Institute of Governmental Studies, said some of the discontent was “likely to be temporary — to do with the pandemic disruptions.” But the poll results may also reflect a longer-term shift that predates the public health emergency.

Moving on to Omicron, officials in Orange County said the variant’s surge had caused more severe illnesses among children, including the deaths of two teens this month alone. Orange County has recorded a total of five pediatric COVID-19 deaths since the start of the pandemic. Three have occurred since December, when the hyper-contagious variant arrived.

One of the teens who died in February was previously healthy and declined to get vaccinated even though her father and his wife encouraged her to do so. The 17-year-old developed a fatal case of multisystem inflammatory syndrome, or MIS-C.

In related news, a study published this week in the Lancet Child & Adolescent Health concluded that COVID-19 vaccines were unlikely to trigger MIS-C. The study, based on data gathered in the U.S., was prompted by the emergence of a handful of cases in people with no detectable evidence of coronavirus infections.

And speaking of vaccines, the CDC has quietly changed its advice on the timing of the first two doses. The agency now says most people getting Comirnaty (the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine) or Spikevax (the Moderna vaccine) should consider waiting up to eight weeks between shots instead of the three or four weeks previously recommended.

Studies show that the longer interval can generate more enduring protection while also reducing the risk of heart inflammation, a rare side effect seen mostly in young men. The new guidance applies to people ages 12 to 64 but not to seniors, people with weakened immune systems or those who need protection fast because they’re at risk of developing a severe case of COVID-19.

Another COVID-19 vaccine may be getting closer to prime time. The pharmaceutical giants Sanofi and GlaxoSmithKline said they’d be seeking regulatory approval for their shot after a clinical trial found it to be 100% effective in preventing severe cases of COVID-19 and 58% effective at preventing any symptoms of the disease. When used as a booster, it increased antibody levels by a factor of 18 to 30.

The shot is based on the recombinant protein technology Sanofi uses to make flu vaccines, and it uses a Glaxo ingredient called an adjuvant to enhance the recipient’s immune response. It doesn’t need to be kept in a deep freeze like the mRNA vaccines, which would make it easier to administer in many countries. Plus, the lack of mRNA may be appealing to those who are wary of the newer technology.

Glaxo’s adjuvant is also an ingredient in a new plant-based COVID-19 vaccine made by Medicago. The plants are used to grow particles that mimic the spike protein on the coronavirus exterior. A clinical trial of 24,000 adults conducted in the pre-Omicron era found that the two-dose vaccine was 71% effective at preventing COVID-19, with mild side effects like fever and fatigue.

Canada authorized the Medicago vaccine on Thursday, becoming the first country to endorse a vaccine made (in part) by plants. It is available to adults ages 18 to 64.

And there’s more good news from Canada: Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has removed the emergency powers he invoked last week to deal with the truckers and other protesters who blocked border crossings and occupied downtown Ottawa. The demonstrators were opposed to vaccine mandates and other COVID-19 rules, and they spent more than three weeks in the limelight before they were shut down by the biggest police operation in the nation’s history.

There had been concern that some of the protesters might try to come back. But Trudeau said Wednesday that the threat had passed.

“We were very clear that the use of the Emergencies Act would be limited in time,” he said. “We said we would lift it as soon as possible.”

The Canadian demonstrators inspired copycat protests in Europe, Australia, New Zealand — and as of Wednesday, the United States. About 100 big rigs and more than 500 other vehicles set off from Adelanto in the Mojave Desert on Wednesday, with a goal of reaching Washington, D.C., 11 days later.

Organizers of the so-called People’s Convoy are demanding the government abandon all pandemic-related mandates and “re-open the country,” according to a statement from the group. Several hundred people gathered for a pre-departure rally where speakers repeated false claims about COVID-19 vaccines. Multiple attendees wore apparel with alt-right and Nazi symbols.

“I just want my freedom back,” said Ken Jones as he waved Gadsden, American and Canadian flags near a line of honking cars. “But maybe also let’s get Trump back in there.”

Your questions answered

Today’s question comes from readers who want to know: Did Omicron infect enough people to get the U.S. to herd immunity?

Not even close.

Millions of people have been infected with Omicron since it was detected here around Thanksgiving, but in a country of more than 332 million, that’s still a far cry from what would be needed to deprive the coronavirus of potential victims to infect. Even when you factor in the nearly 65% of Americans who are fully vaccinated (though not necessarily up to date with their booster shots), there are still plenty of targets for the virus to go after.

Well before Omicron, the CDC had shifted its goals away from achieving herd immunity. The prevalence of breakthrough infections made it clear that the immunity generated by vaccines and past infections waned over time. What’s more, the Delta and Omicron variants replicate so quickly that the virus can take hold while the immune system is still getting its act together (though it usually swings into action in time to prevent serious illnesses).

Dr. Don Milton, who studies the behavior of respiratory viruses in the air, said a more realistic goal was to reach “herd resistance.” That means people would continue to become infected with the coronavirus, but those infections wouldn’t lead to spikes in illnesses that would be disruptive to society.

That’s the situation with influenza — it causes seasonal outbreaks, but they’re not big enough to shut down schools, close businesses or overwhelm hospitals.

We want to hear from you. Email us your coronavirus questions, and we’ll do our best to answer them. Wondering if your question’s already been answered? Check out our archive here.

The pandemic in pictures

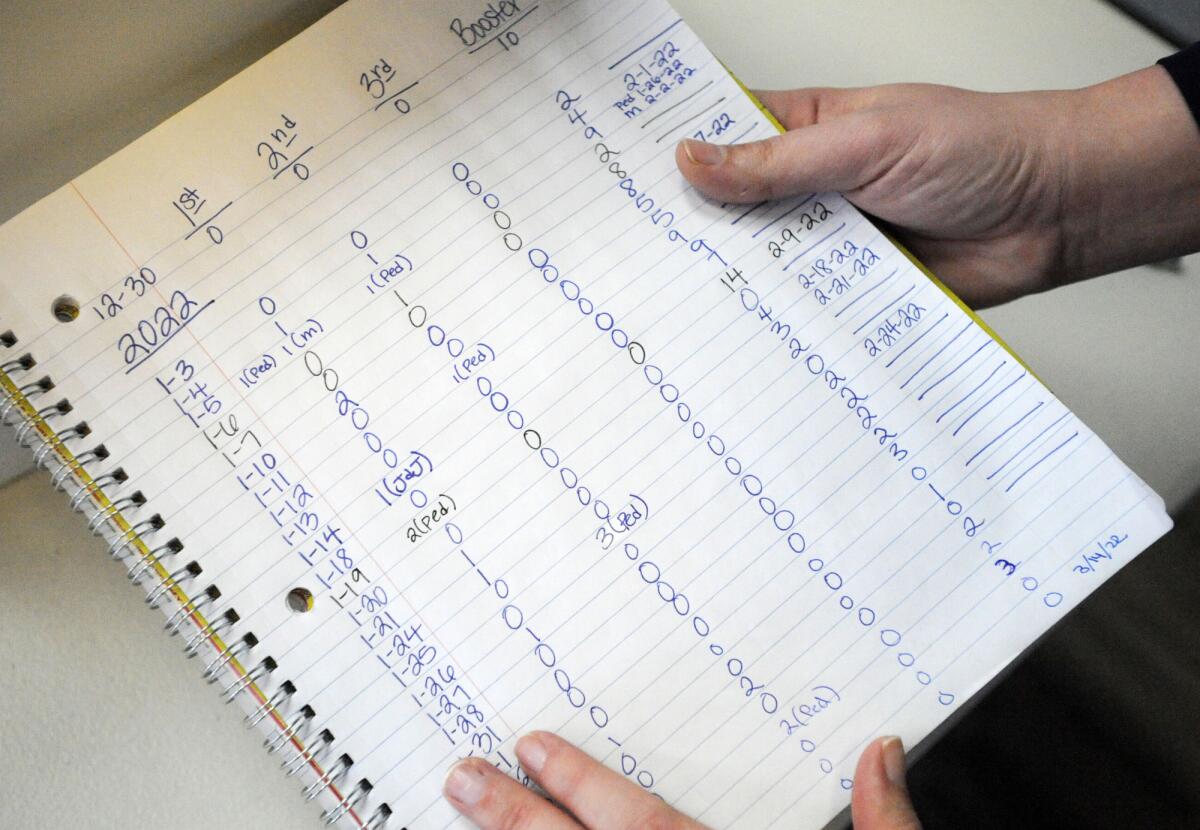

See all those big fat zeros in the notebook above? They represent the number of people coming to the Marion County Health Department in Hamilton, Ala., each day this year to get a dose of COVID-19 vaccine.

I’ll save you having to do the math: Only 14 people in a county of 30,000 residents have dropped in to get a first dose of COVID-19 vaccine this year.

The handwritten log is one of many signs that America’s COVID-19 vaccination campaign has pretty much ground to a halt. If you’re a regular reader of this newsletter (which, if you’ve made it this far, you probably are), this won’t come as much of a surprise.

Across the entire country, about 90,000 people are getting their first COVID-19 shot each day. The last time that number was that low was back in December 2020, when the shots were brand new and supplies were extremely limited.

About 24% of all Americans remain completely unvaccinated, according to the CDC, and many of them are likely to remain that way. Last month, when pollsters asked unvaccinated adults what would persuade them to roll up their sleeves, half of them gave a one-word reply: “Nothing.”

“It was quite demoralizing to see those results, frankly,” said Kelly Moore, a former Tennessee health official who now leads Immunize.org, a vaccination advocacy group funded by the CDC.

Resources

Need a vaccine? Here’s where to go: City of Los Angeles | Los Angeles County | Kern County | Orange County | Riverside County | San Bernardino County | San Diego County | San Luis Obispo County | Santa Barbara County | Ventura County

Practice social distancing using these tips, and wear a mask or two.

Watch for symptoms such as fever, cough, shortness of breath, chills, shaking with chills, muscle pain, headache, sore throat and loss of taste or smell. Here’s what to look for and when.

Need to get a test? Testing in California is free, and you can find a site online or call (833) 422-4255.

Americans are hurting in many ways. We have advice for helping kids cope, resources for people experiencing domestic abuse and a newsletter to help you make ends meet.

We’ve answered hundreds of readers’ questions. Explore them in our archive here.

For our most up-to-date coverage, visit our homepage and our Health section, get our breaking news alerts, and follow us on Twitter and Instagram.