Kawhi Leonard didn’t spark Canada’s love of basketball, he completed it

- Share via

TORONTO — As he became known as one of Canada’s best teenage basketball players, Javonte Brown-Ferguson had a decision to make.

Prep schools in the United States were wooing the 6-foot-11, 230-pound center. It was an attractive opportunity. Many top Canadian recruits had used the same pipeline to reach the NBA.

Instead, he stayed at Thornlea School, 18 miles from downtown Toronto, driven by a belief that would have been considered radical in the not-too-distant past.

“I had a lot of options,” Brown-Ferguson said, “but I really thought Canada would get me the best prepared.”

Where Canadian basketball players used to operate in no-man’s land, on the fringes of the game’s attention while feeling like outsiders within the borders of a country where hockey reigned supreme, they now play in the thick of what has become one of the world’s hoops hotbeds. Brown-Ferguson didn’t have to look far for evidence he could accomplish what he wanted without leaving his backyard.

He had to think back only to June’s NBA Finals, when Kawhi Leonard led Toronto to its first NBA championship.

Leonard, who returns to Toronto on Wednesday for his first game since leaving the Raptors in free agency for the Clippers, did not spark a basketball boom. It had been building in Canada for decades. Sixteen Canadians were on opening-night rosters this season in the NBA, the most for any non-U.S. country.

But numerous basketball figures in the country credit the superstar forward’s championship in his lone season with the Raptors as amplifying the game’s reach and creating a new wave of interest.

“He’s a legend now, forever,” said Chris Boucher, the Montreal-raised Raptors forward.

Said Dwight Powell, a Dallas forward who grew up in Toronto: “As a kid, if I were watching, I would remember this past summer for the rest of my life.”

When Leonard threw his fists into the air following Toronto’s title-clinching Game 6 of the NBA Finals at Oakland’s Oracle Arena, Raptors broadcaster Leo Rautins watched the team climb to the top of the NBA from his courtside seat. He viewed it as a new era as well as the culmination of decades of momentum.

The Toronto Raptors are in the playoff hunt this season without Kawhi Leonard because of experience they gained winning big games with or without him last year.

“I’m a Toronto boy, I played ball when nobody cared when that was,” said Rautins, who played at Syracuse and was a first-round draft pick in 1984. “To see where we’ve gone from that point where you just had some closet basketball happening — and it was good, but such a small amount — to what we have now, it really was emotional.”

Though invented by a Canadian, James Naismith, basketball took decades to gain a foothold in his home country.

“You thought about badminton before you thought about basketball, lawn darts before you thought about basketball,” said Bill Wennington, a seven-foot center on title-winning Chicago Bulls teams in the 1990s. Wennington was born in Montreal and played hockey until he was 12, stopping because his feet were too big for skates.

In 1995, when Doug Smith told others he was the beat reporter covering the Raptors’ inaugural season, he grew accustomed to receiving strange looks and comments like, “You don’t like hockey?” Smith liked basketball, but moreover saw Canada’s shifting demographics.

“More people are coming in who aren’t invested in hockey,” said Smith, who continues to cover the team for the Toronto Star. Kids now “watch basketball or play soccer and it’s the new Canada. And basketball was the driver of that.”

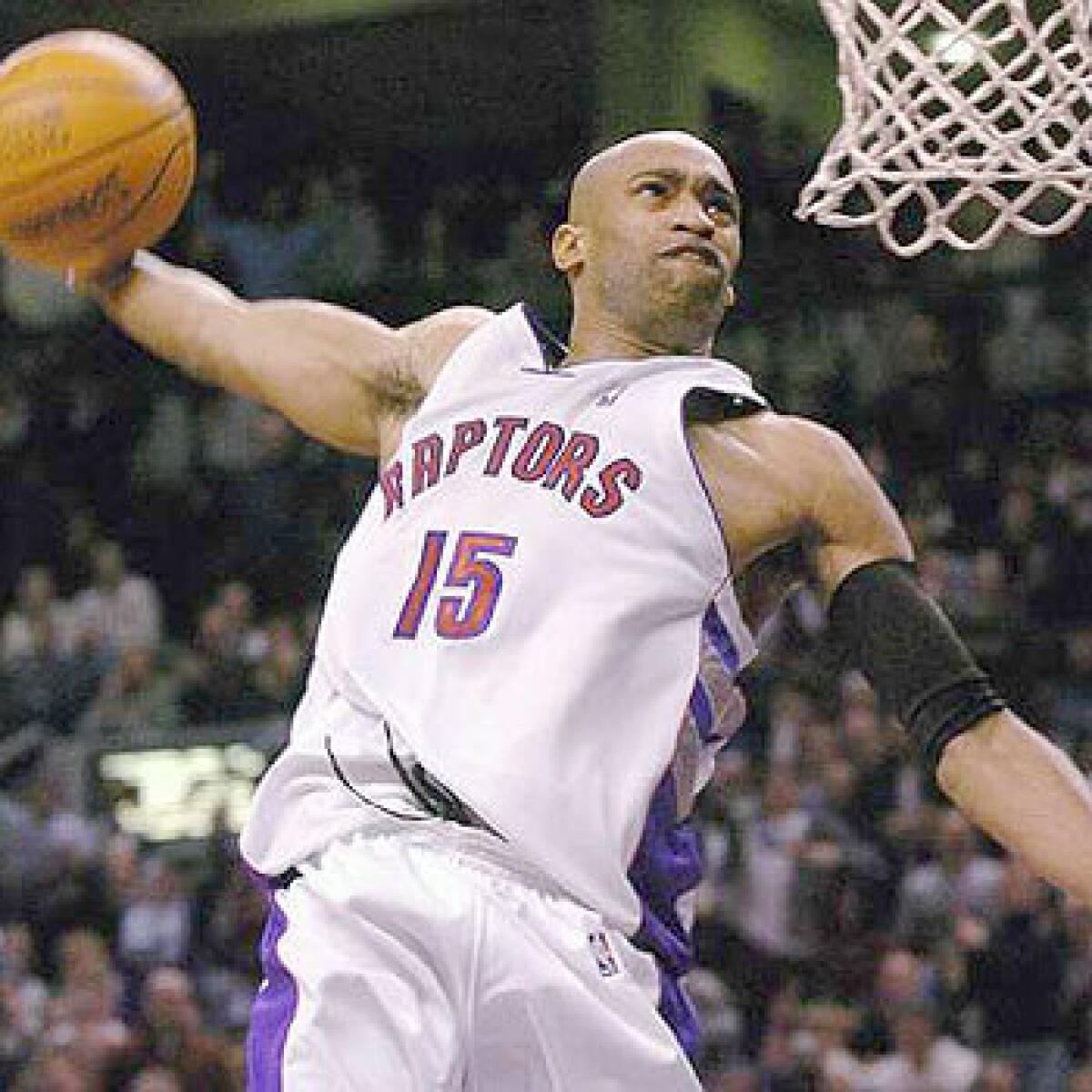

It began in earnest in 1995 with the arrival of the Raptors and Vancouver Grizzlies in the NBA, said Miami forward Kelly Olynyk, whose father was a guest coach with the Raptors and mother worked as a Raptors scorekeeper for nearly a decade before the family moved to British Columbia. Kobe Bryant is the favorite player of both Brown-Ferguson and New Orleans rookie Nickeil Alexander-Walker, but others were inspired by Vince Carter, whose acrobatic slam dunks made him Toronto’s first breakout star, Raptors forward Chris Bosh and point guard Steve Nash, the two-time NBA MVP with Phoenix who was born in British Columbia.

At the youth levels, a shift away from hockey toward sports such as basketball and soccer began. Rautins coached the men’s national team from 2005-11 and helped basketball’s governing body in the country pivot to a focus on developing young players and the coaches who taught them. At the same time, Canadian club teams and prep schools rose to prominence to cultivate homegrown talent. One club, CIA Bounce — created by Tony McIntyre, the father of NBA point guard Tyler Ennis — has produced two players selected first overall in the NBA draft in Anthony Bennett and Andrew Wiggins.

The ability to recruit in Canada now gets college coaches hired.

“It’s like we’re almost an extension now of the United States with high school, college recruiting and the NBA,” Olynyk said. “It’s like the border isn’t even there anymore.”

Twelve Canadians played in the NBA between 1947 and 2000; that many have joined the league since 2017, with six first-round picks among them. Those players, including Denver’s Jamal Murray, Oklahoma City’s Shai Gilgeous-Alexander, the former Clippers all-rookie guard, and Clippers rookie forward Mfiondu Kabengele, are among a generation that grew up predominantly near Toronto knowing the city as an NBA destination.

After the playoff heroics of Leonard, the Southern Californian named the MVP of the Finals for the second time in his career, another generation will now grow up only knowing Toronto as an NBA champion.

“When we won, it was amazing the way it changed the ways people were thinking about a lot of stuff,” Boucher said. “Just to know that it’s possible for the kids. A lot of kids might start playing more basketball now.

“It opened a lot of doors that had been closed and opened the eyes of people to show them Canada is interested in basketball.”

They’re not just interested but “hungry,” Brown-Ferguson said.

He watched Game 6 during a tournament in Scottsdale, Ariz., and could not wait to return home to take in the celebration and continue his own basketball career. Recruiters followed him across the border in droves.

In November, he committed to Connecticut over Kansas and Texas A&M, maybe the next player to push Canada’s profile even higher.

Times staff writer Dan Woike contributed to this report.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.