Paul Pettit’s legend extends beyond 70th anniversary of 27-strikeout game

- Share via

The letters arrive every now and then, and they always bring joy.

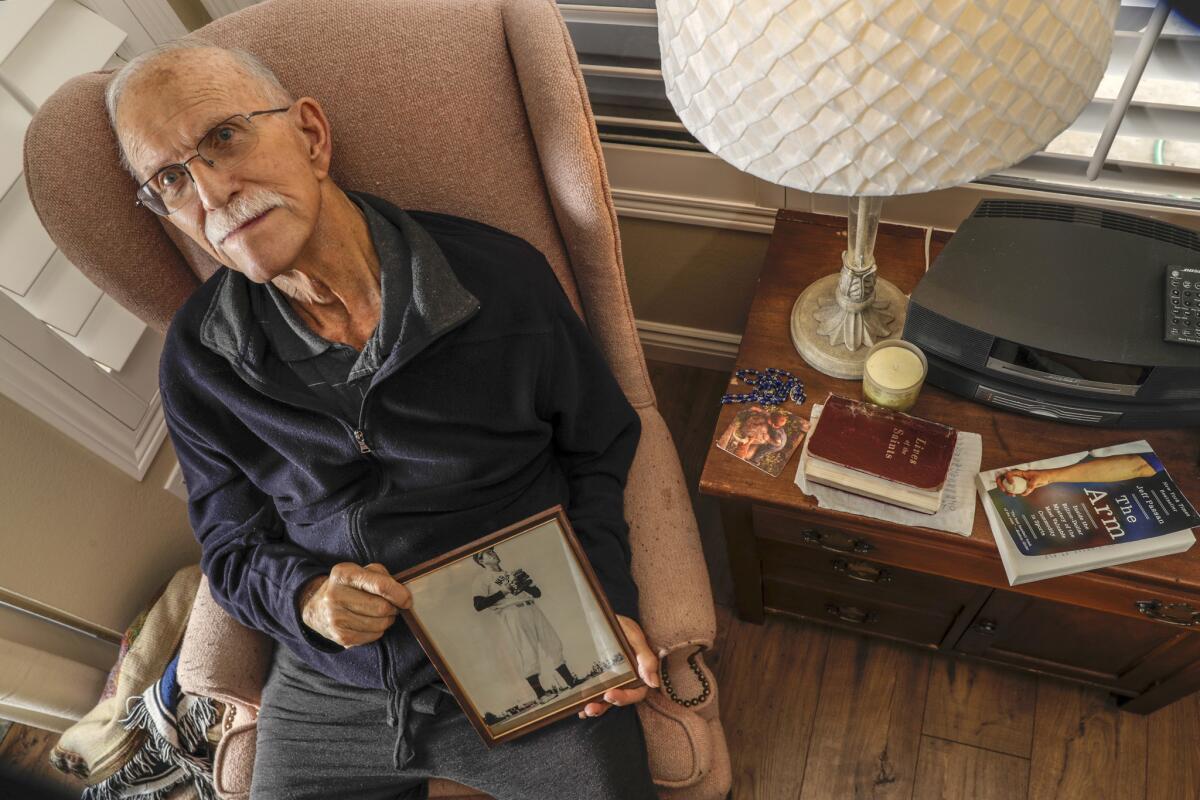

Nearly 70 years after he stepped into a unique place in baseball history, Paul Pettit remains adored. His newlywed wife, Sally, gets a kick out of it, too.

“He still gets fan mail,” she said with a touch of giddiness.

Pettit recently checked off a new box when he retrieved his mail.

“My crowning achievement, I got one from Japan,” Pettit said. “I saved it. I even framed it and put it up in my garage.”

Those tasks aren’t easy for Pettit these days. He is 87 and he doesn’t move well. He has an arthritic condition in his spine that crowds the nerves to his arms and legs. But he’s still as sharp as the fastballs that made him the first $100,000 “bonus baby” in Major League Baseball history.

Pettit can well recall the details of a life that made him the most sought amateur pitcher in America at 18, a strapping, flashbulb-inducing left-hander who struck out 27 batters in a 12-inning game for Harbor City Narbonne 70 years ago Sunday.

After he was courted by a Hollywood movie producer in a Sunset Boulevard office in 1949, Pettit signed baseball’s first six-figure bonus, with the Pittsburgh Pirates. He rubbed elbows with Bing Crosby and Jayne Mansfield and was guided by Branch Rickey, who had signed Jackie Robinson.

And it all blew up with one pitch in a minor league ballpark in New Orleans in 1951.

Pettit remembers a lot, although he didn’t know his pitching line in that 27-strikeout game. Told he issued three walks and allowed four hits, Pettit said, “That’s good for me. I usually walk more than that.”

The ‘Wizard of Whiff’

That game, on May 11, 1949, against Wilmington Banning, always came up in conversation with Pettit and Darrold “Gar” Myers, his catcher and a lifelong friend who died about three months ago, Pettit said.

In addition to guiding Pettit behind the plate, Myers ended the game with a walk-off home run.

Pettit’s performance that day was flash point to the hype that surrounded him, attracting crowds to Narbonne so large that bleachers were moved from the football field.

During his high school career, he threw six no-hitters and, according to the Society for American Baseball Research, struck out 390 batters in 140 innings. That earned him the nickname “The Wizard of Whiff.”

The 6-foot-2 Pettit estimates that his fastball reached the mid-90s in miles per hour, and he also threw a baffling slow curveball.

“There hasn’t been a schoolboy pitcher like him around like him for a long time,” Rickey said, according to a Los Angeles Times story. “He’s the Bob Feller type, definitely, and maybe, this time next year, a lot of people will know it.”

Pettit said he was warming up in the bullpen for the Dorsey Tournament when scout Babe Herman of the Pirates approached him. Herman told Pettit he was worth at least $90,000, an unprecedented figure at the time.

Then, the chase for Pettit took a dramatic turn when filmmaker Frederick Stephani offered Pettit $60,000 for the rights to his story. Pettit turned it down before his father, George, during a meeting with several lawyers in a downtown L.A. office, negotiated for $100,000.

Sign up for our daily sports newsletter »

The deal circumvented the bonus signing rule, which required that players who signed for more than $4,000 to spend two seasons on a major league roster, because teams would have to go through Stephani to sign Pettit. Pirates general manager Roy Haney won the sweepstakes and landed Pettit upon his graduation in January 1950.

Pettit ordered the $100,000 — equivalent to more than $1 million today — be paid out equally over 10 years, for tax purposes. He bought his parents a new house, for $12,500, and requested the Pirates pay for the honeymoon with his first wife, Shirley. The couple was given $750.

Pettit did splurge on himself and bought a new, red, four-door Ford sedan. “Nothing special,” Pettit said. “It was a nice car, though.”

Pettit was only 18, and someone wanted the rights to his life story. Surreal, yes, but it made sense to Pettit because Stephani, the producer for “Flash Gordon,” wanted a sports story to tell on film, and he lacked the money to secure bigger names such as Ted Williams or Joe DiMaggio.

“He elected to go with me, figuring that I would really be the next up-and-coming star,” Pettit said. “It didn’t turn out that way because I hurt my arm. I don’t know if it would have [worked out] anyway.”

‘That’s it’

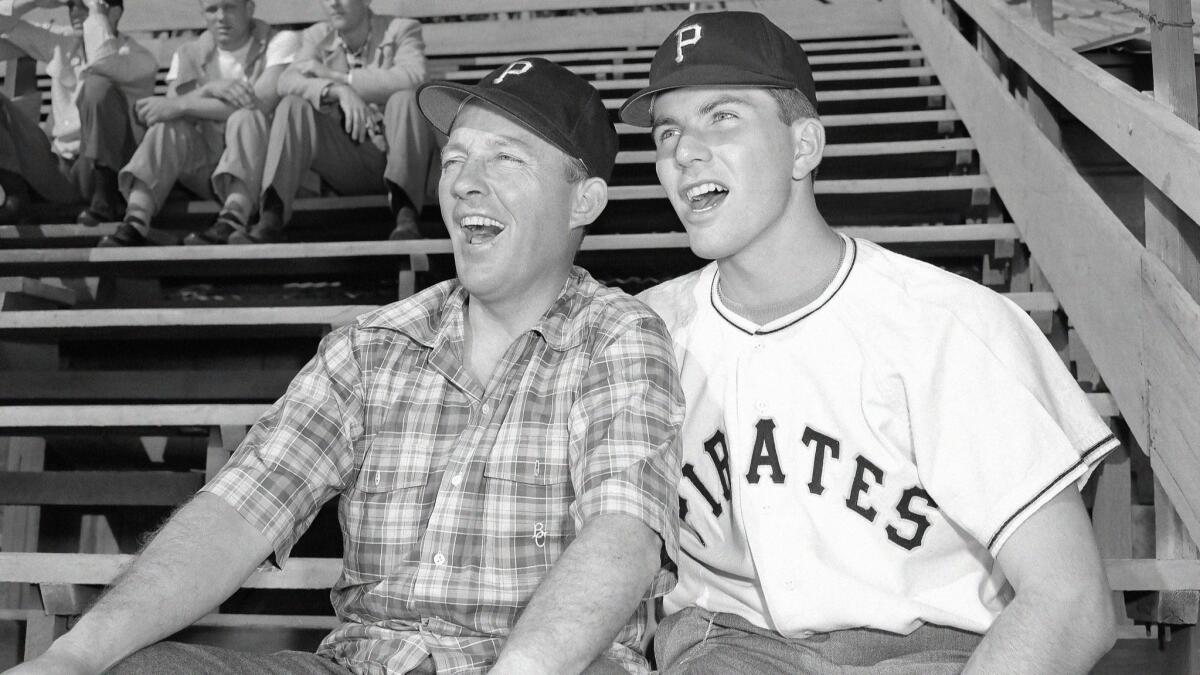

When Pettit reported to rookie camp in San Bernardino, he was summoned for a promotional photo with Crosby, a part owner of the Pirates.

“He was a real down-to-earth guy, really easy to talk to, made me feel at ease,” Pettit said. “We spent maybe a half hour together taking pictures. It was fun.”

Pettit earned respect from his new teammates by working hard in every drill to show that the bonus baby was “no slouch.” He was sent to the New Orleans Pelicans for his pro debut, and his demise began on an innocent throw that injured his elbow.

“It really hurt,” he recalled. “I threw a pitch between innings. It was not during the game. I called the trainer out and said, ‘There’s something wrong with my arm.’ So he came out, and the manager came out with him. I said, ‘Oh, I think I’m OK.’ And I threw one more pitch, and I really felt that. I said, ‘That’s it.’ ”

Pettit saw doctors in Baltimore and was told to rest. When he resumed, the pain rose up to his shoulder and he could barely reach the plate during a game in Memphis. Pettit’s velocity was never the same. He made his major league debut in relief against the New York Giants on May 4, 1951 and retired the side, starting with Bobby Thomson.

Pettit returned to the minors before he made his first major league start, against the Cincinnati Reds, on May 1, 1953. He lasted 6 1/3 innings for his only win. Pettit never returned to the majors after that season. He was 21.

Looking back, Pettit cites overuse for his arm injury. He threw 155 pitches in his first pro start. He threw between games too. Surgery was never considered.

“I was never taken out of a game, ever, ever, until my first start in pro ball,” he said.

Sent to the Hollywood Stars of the Pacific Coast League by then-Pirates general manager Rickey, Pettit reinvented himself as a hitter. The transition was Rickey’s idea, and Pettit thrived at since-razed Gilmore Field, where celebrities such as Mansfield showed up.

“I sat right next to her at a photo shoot,” Pettit said. “I wish I had a shot of that.”

Pettit’s baseball career ended in 1961, two years after the final installment of his bonus was paid. He had the foresight to work on his college degree in the off-seasons and earned a degree in education; he enjoyed a 30-year teaching career at Lawndale, Lawndale Leuzinger and Long Beach Jordan high schools.

While his fame was fleeting, his story lives on. Tim Pettit, one of his six children and a former pitcher in the Angels’ system, remembers a 1979 encounter with Warren Spahn, a Hall of Fame pitcher who served as a roving instructor.

“All the pitchers were lined up and he said, ‘I’d like to know, who is Paul Pettit’s kid? How’s he doing?’”

Said Tim Pettit, “It’s just really flattering to see the respect the old-timers had for him.”

Paul Pettit is content with his legacy. The movie was never made, but his story seems fit for the big screen.

“It’s kind of fun to have the notoriety,” Pettit said. “There’s a certain amount of adulation that goes along with it.”

After a 65-year marriage to Shirley, who died in 2016, Pettit married Sally and was reenergized at their wedding.

“He was dancing,” Sally said.

The two live a quiet life in Canyon Lake, not far from Pettit’s 1950 photo-op with Crosby, with a postcard view of a park and lake across their street.

Sadly, Pettit’s condition could worsen. In a cruel twist, he’s lost some use of his left hand, the one that brought him all that adulation.

But he can still open a mailbox for the latest fan mail.

Twitter: @curtiszupke

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.