John Madden: Given choice of any QB, I’d pick Stabler first

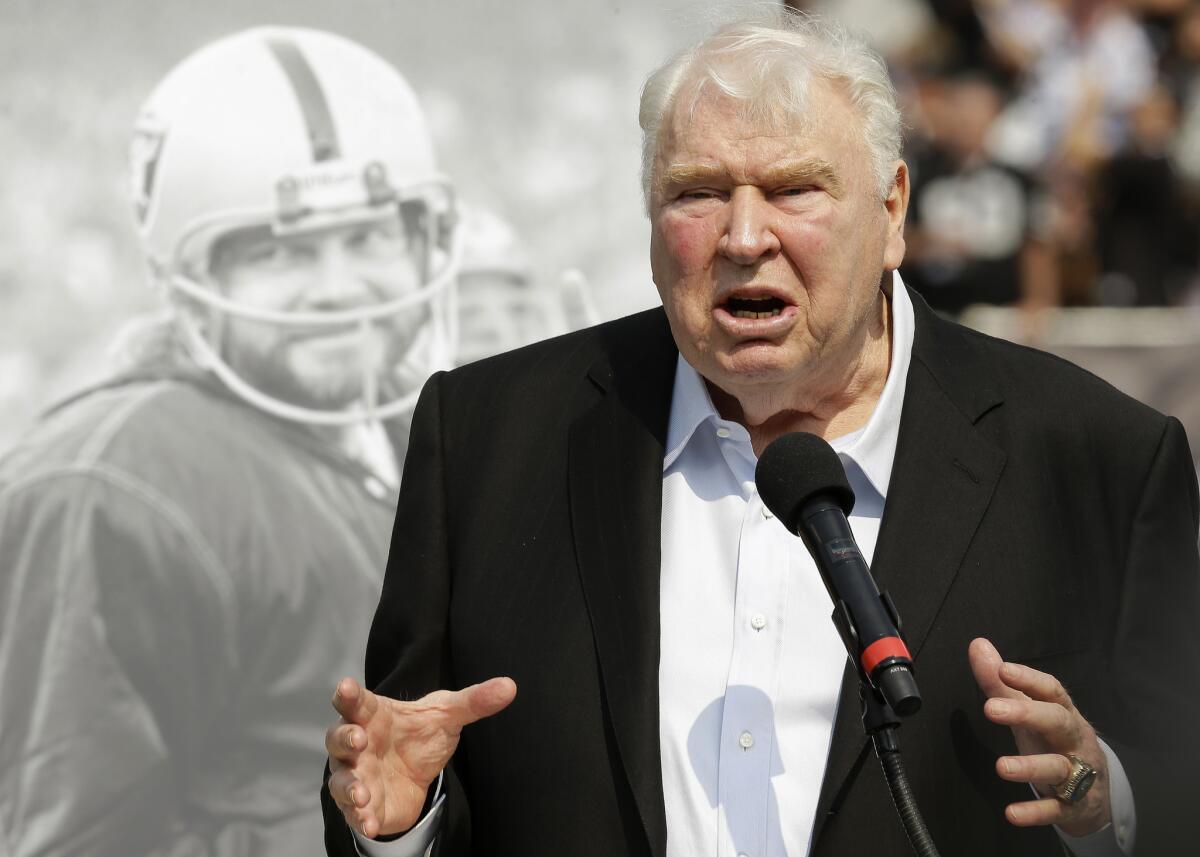

Former Raiders Coach John Madden discusses Ken Stabler at a ceremony honoring the late NFL quarterback on Sept. 13, 2015.

- Share via

The tears come easily for John Madden, as do the flowing memories, at the mention of Kenny “Snake” Stabler.

“If you’re ever going to play a game and you have to choose sides, and you’re not even exactly sure what the hell the game is,” Madden told The Times this week in a rare phone interview, his voice thin and trembling, “you’d pick Stabler first.”

Stabler, the Super Bowl-winning Oakland Raiders quarterback who died of colon cancer in July 2015, will be inducted Saturday into the Pro Football Hall of Fame. His family and friends will be there, including Madden’s sons, Joe and Mike, and grandsons.

Madden, the legendary coach, broadcaster and video game magnate, whose own Canton enshrinement came a decade ago, will not be making the trip to Ohio. He’s recovering from open-heart and hip-replacement surgeries earlier this year, and will watch the ceremonies from his home in Pleasanton, Calif.

“I’m getting better,” he said. “It’s a slow process. I got piled on, it happens … But, hell, you didn’t call so we could talk about me.”

For Madden, Stabler’s family and many others, the quarterback’s official inclusion in the pantheon of football greats is long overdue. Stabler, who played for Oakland from 1970 to 1979, was involved in some of the most memorable plays in Raiders history, ones so well known that they earned their own monikers: “Ghost to the Post,” “Sea of Hands,” and the “Holy Roller.”

At one point, he held the NFL record for reaching 100 victories the fastest, doing so in 150 starts and breaking Johnny Unitas’ mark of 153. Since, only Terry Bradshaw (147), Joe Montana (139), and Tom Brady (131) reached 100 wins in fewer starts.

“I’ve been waiting for this one for a long time,” Madden said. “I remember all those games we’d play, he’d win them. On the road, his percentage, I just figured he’d be a first-ballot Hall of Famer. And, lo and behold, he’s not going in until now. That’s difficult. It’s difficult for the family.

“But like I told them, once you’re in, you’re in. You don’t look back and say when you got in. They’re all happy now. I hate to miss it.”

While others fixated on the perceived injustice of the quarterback’s long wait — he retired in 1984, after stints with the Houston Oilers and New Orleans Saints — Madden doesn’t remember Stabler ever complaining about it.

“He didn’t talk about it at all,” the coach said. “I don’t remember him saying one word about it. I think more importantly, I don’t think he ever thought about it. You’d say, ‘How could a guy be that good, win that many games, and not think about the Hall of Fame?’ That’s Kenny Stabler. That’s who he was.”

Stabler’s enshrinement class includes fellow players Brett Favre, Marvin Harrison, Orlando Pace, Kevin Greene, and Dick Stanfel, coach Tony Dungy and owner Eddie DeBartolo.

There are Los Angeles connections to this class, but not strong ones. Pace, a towering tackle, won a Super Bowl with the Rams, but when the franchise was in St. Louis. Greene, a linebacker/defensive end who had 160 sacks, began his career with the Los Angeles Rams, playing with them from 1985 to ‘92, but prefers to associate himself with the Pittsburgh Steelers, where he played from 1993 to ‘95.

“I really bleed black and gold,” said Greene, who played for Carolina and San Francisco in the last of his 16 seasons. “That really was the pinnacle of my career. We just crushed people. We had the right attitudes on defense.”

As for Stabler, he defined the Silver and Black, and his deliberate Southern style — reflective of his roots in Foley, Ala. — was a sharp contrast to his excitable young coach with the larger-than-life personality.

“The bigger the game, the calmer he got,” Madden recalled. “He was just the opposite of me. I’d be running up and down, and he’d be completely calm.

“That’s one of the things that made him such a great quarterback. He could have a bad play and just erase it.”

Stabler didn’t throw a lot of high passes. He didn’t want to leave his receivers unprotected. So when he missed on a throw, it was typically into the ground.

“He had a saying,” Madden said. “If he threw one in the dirt, he’d say, ‘Low-ball thrower, highball drinker.’ He’d say it real fast, then move on to the next play. There’d be no more thought about it.”

What he did after the snap was only part of Stabler’s excellence, Madden said. It started with his strategic decisions as a play-caller.

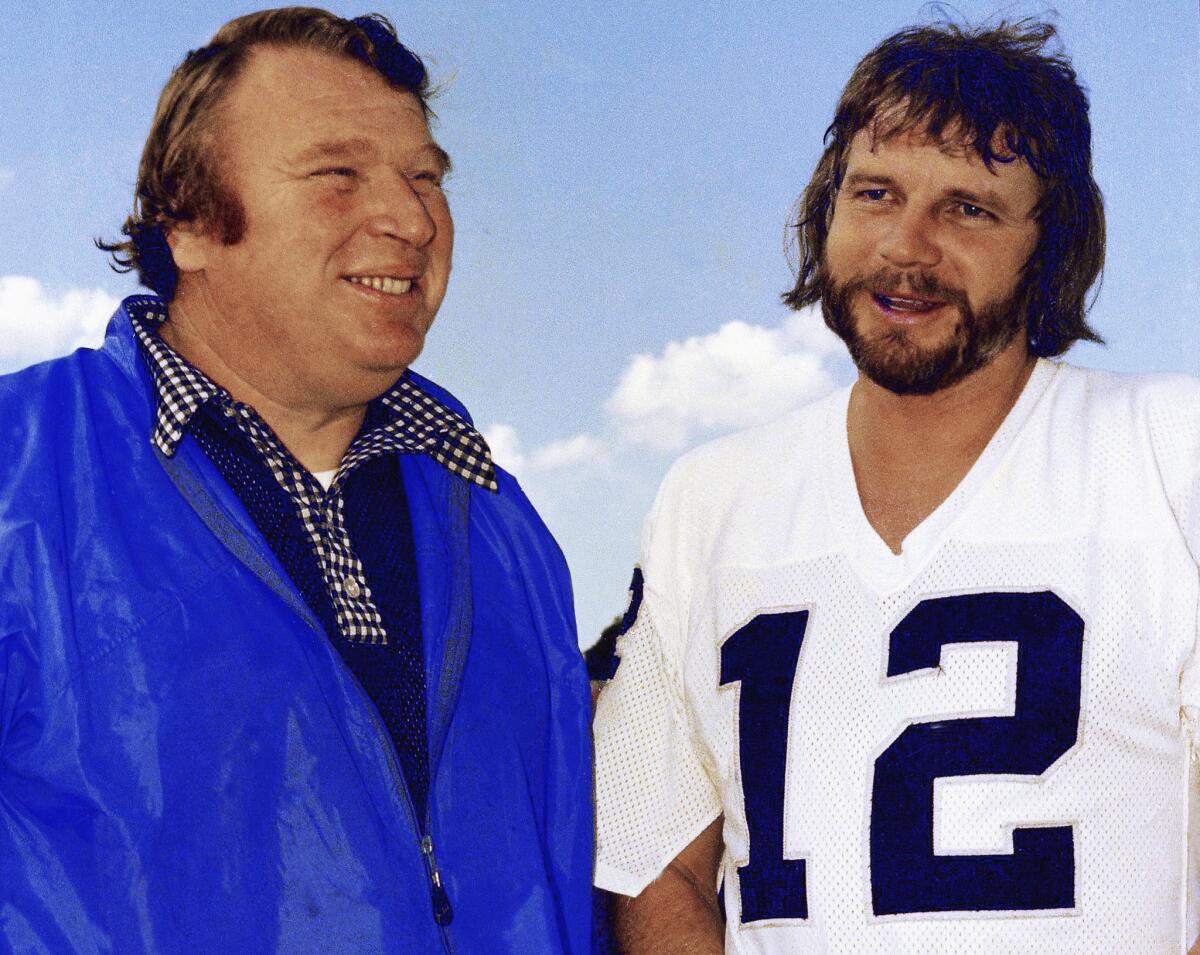

Raiders quarterback Ken Stabler, right, talks with Coach John Madden in Oakland, Calif. on Jan. 4, 1977.

“They kind of made a caricature of Kenny Stabler as some guy who was staggering around and didn’t know what the hell was going on,” Madden said. “He knew what was going on. He was very bright and worked very hard.

“We always talked about guys like Snake and [Pittsburgh’s] Terry Bradshaw who called their own plays. That’s when they called the quarterback the field general. The biggest part of calling those plays is being able to do something when they didn’t expect it. … He’d set you up. He put a lot of thought into it, and the play he’d run wasn’t what you thought it’d be.”

Madden said he doesn’t anticipate football ever returning to a time when quarterbacks have so much control of an offense — nor does he advocate that with today’s quarterbacks — but he’s also nostalgic about the days Stabler did it.

“When a player calls a play, it was, ‘We’re going to do this, and we’re all in this together,’” he said. “When a coach called it, it was, ‘They want us to do this.’ They didn’t take ownership of it.

“When Snake called a play, they took total ownership. Whatever he said, they believed.”

sam.farmer@latimes.com

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.