His dreams of basketball stardom vanished first. Now his mother says, ‘I am not giving up on finding my son’

- Share via

Rico Harris slipped out of his mother’s duplex on a dead-end street in Alhambra and into the darkness.

The big man with “BALLIN IV LIFE” and a basketball tattooed on his left arm folded himself into a black Nissan Maxima. Harris had been awake for almost 30 hours. His mother had urged him to rest at home for a few hours. He seemed out of sorts.

Late on the warm October night 2½ years ago, the car would have been another anonymous streak of lights winding north on Interstate 5. Each mile pulled Harris farther from his past.

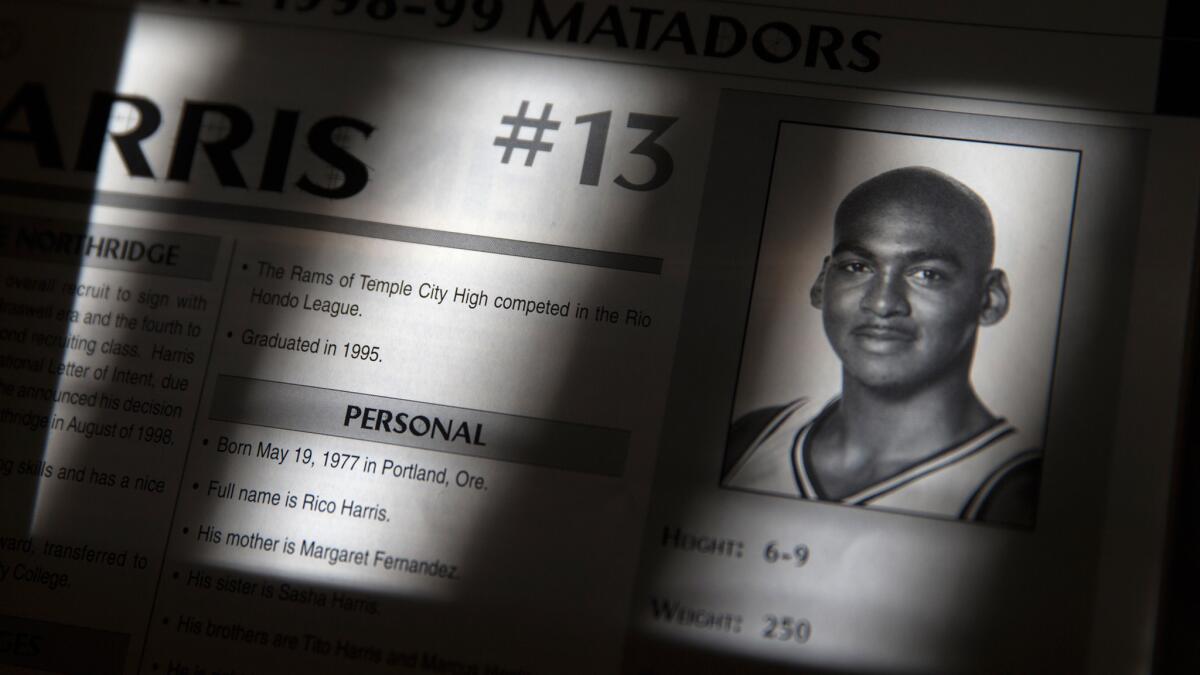

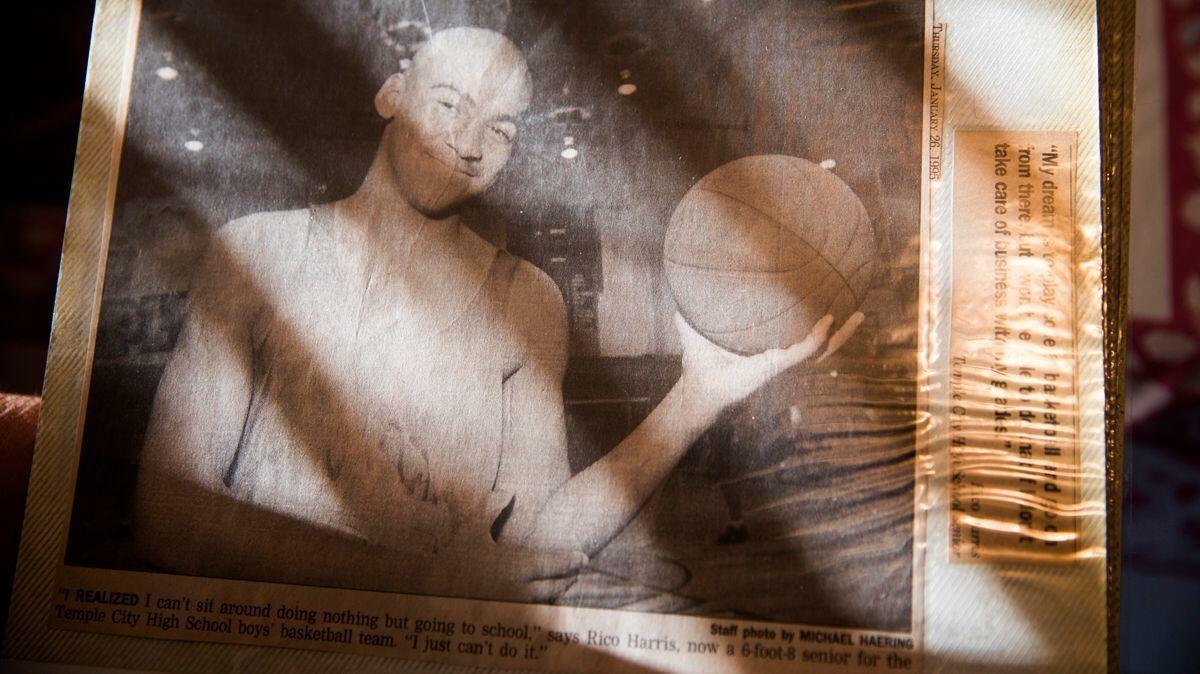

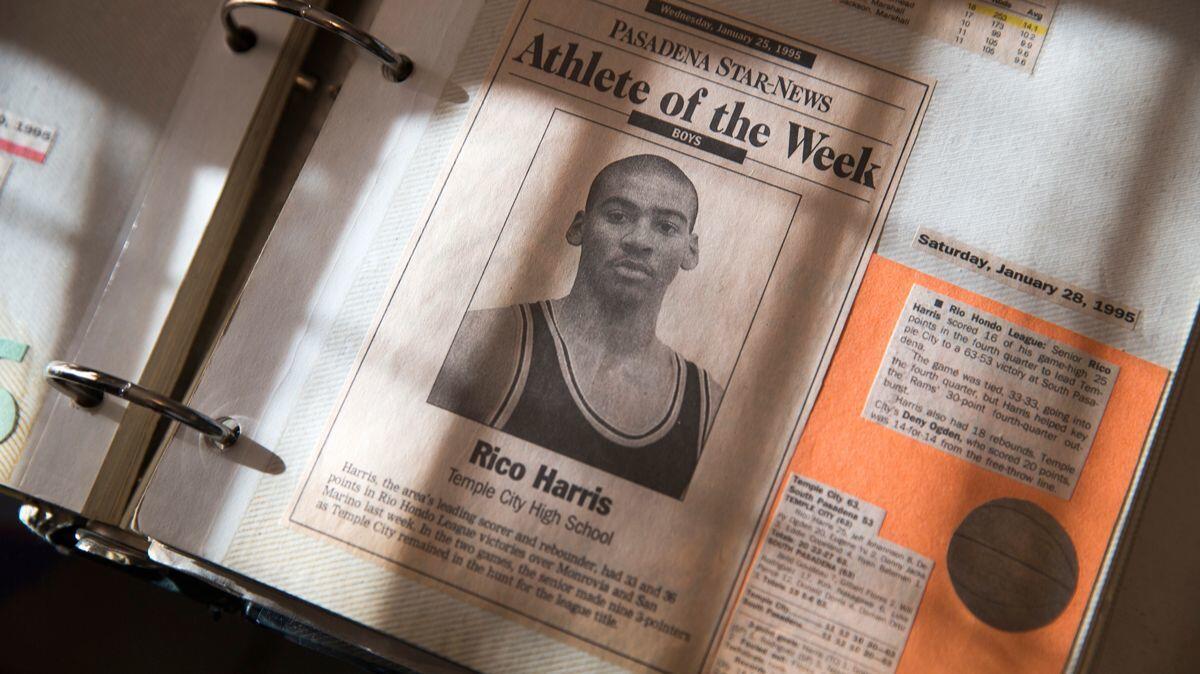

Some of the country’s top college basketball programs once pursued him. At Temple City High School, he clung to a childhood goal of being a first-round pick in the NBA draft. Harris fixated on providing for his mother when — not if — he made it. And, really, fulfilling the dream seemed inevitable for the 6-foot-9 kid with an uncanny ability to shoot a basketball.

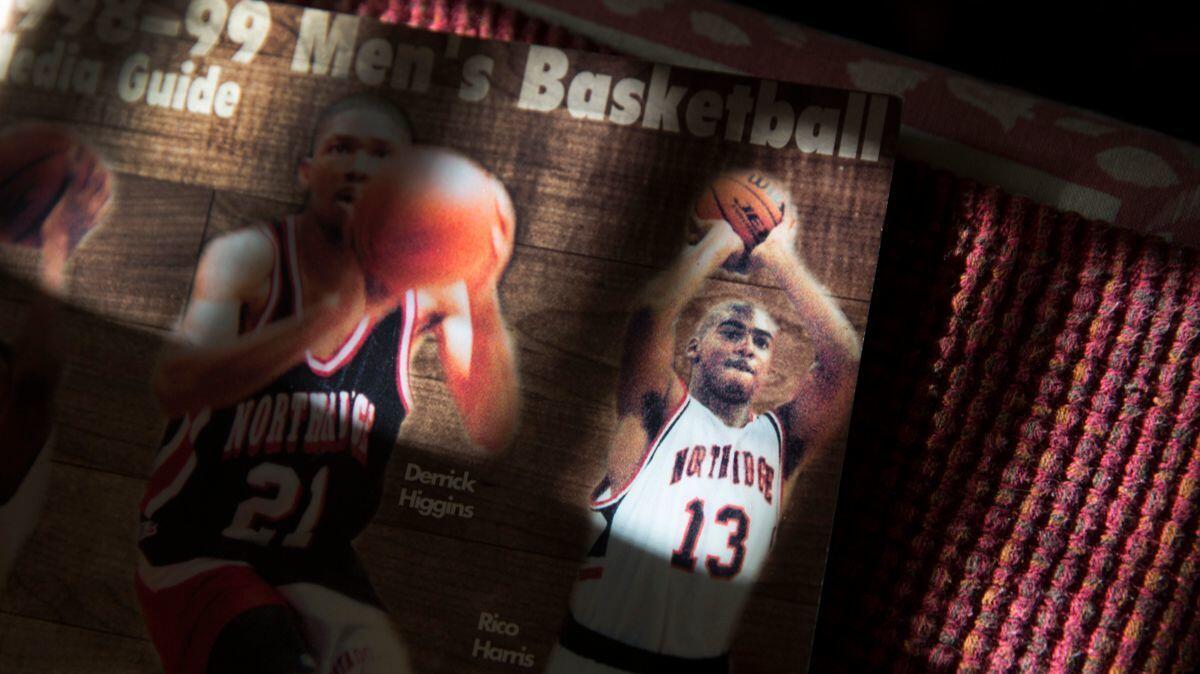

Instead, Harris bounced from Arizona State to Los Angeles City College to Cal State Northridge. He spent a half-tour with the Harlem Globetrotters in 2000 before his career vanished. Harris blamed a bad back, distaste for the gimmick-filled style of basketball the Globetrotters played or coordination problems after being hit in the head with a baseball bat while trying to break up a fight.

“I saw firsthand Rico could’ve had a million-dollar check, easy, easy, easy,” said Chrison Thompson, a longtime friend and teammate at L.A. City College. “Something happened to my brother in his spirit that didn’t allow him to break through the ceiling.”

Harris didn’t talk much about the aborted career, even with close friends. One of them nicknamed him “Houdini” for his ability to drop out of sight.

As the car cut through the night, Harris, 37, carried the disappointment of another failure. Drinking had cost him a job as a security guard for an event management company. Harris felt like he had let down his mother, let down friends, let down everyone.

He planned to push aside nagging doubts and move in permanently with his girlfriend in Seattle. He would restart life 1,100 miles from his past. He would leave the failure behind.

Then Harris disappeared.

Something happened to my brother in his spirit that didn’t allow him to break through the ceiling.

— Chrison Thompson

::

A Yolo County sheriff’s deputy discovered the Nissan in the parking lot at Cache Creek Regional Park on Oct. 13, 2014. He didn’t find anyone in the area along State Route 16 about an hour northwest of Sacramento. The next day the deputy noticed the car hadn’t moved, checked the registration and learned Harris hadn’t been heard from since Oct. 10.

The car’s gas tank was empty, battery dead and interior ransacked.

Authorities scoured a 27-mile stretch of the two-lane road that winds through the Capay Valley’s steep hills and organic farms. They used dogs and all-terrain vehicles, hiked the rugged area and summoned a California Highway Patrol airplane with a heat-seeking camera.

They couldn’t find Harris. But, really, he had been missing long before the detour into the valley.

As a youngster, the soft-spoken kid hated confrontation and towered over other children on the playground at Alhambra’s Fremont Elementary School. He joined pickup basketball games with adults at the Granada Park gym by age 11. No one doubted his talent. He didn’t talk about fancy cars or jewelry. Instead, the oldest son of a single mother wanted to create a better life for her through basketball.

Connecticut wanted Harris. So did Kentucky. And UCLA. Scholarship offers rolled in for one of the country’s top 100 recruits.

Harris chose Arizona State, but he wasn’t eligible as a freshman in the fall of 1995. His stay in Tempe, Ariz., was short-lived after being arrested along with two teammates on suspicion of unlawful imprisonment. The men were never charged for the on-campus incident with two women.

Done with Arizona State, Harris retreated to L.A. City College. He led the team to the state junior college title in 1997 and returned for a second season after a failed class blocked a transfer to Rhode Island. Problems followed, including a six-game suspension for breaking team rules.

David Lara, a friend and neighbor since elementary school, believed substance abuse hampered Harris on the court. He declared for the NBA draft in 1998, then backed out. He flirted with Rhode Island again before making an unexpected phone call to tell Bobby Braswell, then head coach at Northridge, he would play at the school to remain close to his mother, Margaret Fernandez, and three siblings.

“I was tired of everybody pressuring me,” Harris said at the time. “I was stressed out.”

Trouble continued at Northridge. Another suspension. He missed the final two games of the season, then didn’t return Braswell’s calls or show up for a scheduled meeting.

“He wasn’t an easily satisfied guy,” Lara said. “From his perspective, oftentimes he wasn’t given a chance to be his best. The only time he was really coachable and likable was in high school. That’s when he wasn’t experimenting with drugs and alcohol.

“He wasn’t good at dealing with people and their expectations. People who tried to play the father role were almost always the enemy to him.”

No NBA team gambled on drafting Harris in 1999. The one-time phenom faded to the fringe of professional basketball, appearing briefly for the San Diego Stingrays and St. Louis Swarm in the now-defunct International Basketball League.

Harris’ prospects didn’t improve with the Globetrotters in 2000. Curley Johnson, a mainstay with the team for 18 seasons, remembered him as likable and quiet. Harris wasn’t one of the main characters, just one more name on the team’s revolving-door roster.

“Things went downhill after that,” Fernandez said. “It had a lot to do with him not having the career he wanted to have, feeling like he had become a failure.”

Maybe the story is familiar. The tendons, cartilage and even the mind upon which the dream is built aren’t enough to sustain it. The can’t-miss prospect fails. The body and mind usually recover. Life goes on. But Harris couldn’t shake the defeat.

Between 2001 and 2007, he faced 16 cases in L.A. County Superior Court on a slew of charges including public intoxication, burglary and trespassing. He bounced in and out of jail. He was diagnosed with bipolar disorder, but stopped taking medication because he didn’t like how it made him feel.

Harris still dropped by the Granada Park gym for pickup games, sometimes high and mumbling to himself. Once he wore flip-flops from a stint in jail. Lara barely recognized his old friend when they crossed paths in downtown Alhambra. Harris didn’t seem to have purpose without basketball.

“He fell off into his own world,” Lara said.

One day during that bleak time, Harris brought a badly injured kitten to his mother’s house. He found it alongside a road. He didn’t want it to die alone.

::

The big man met Jennifer Song at an L.A. restaurant in early 2012 while he worked security. Harris snapped her picture; she was visiting from Seattle and asked if he could text it to her. That started their connection.

Harris had been sober for about five years, helped by a program in downtown L.A. operated by the Salvation Army after an overdose almost killed him. He eventually took a job as a cook for the organization, then helped out as a security guard at a homeless shelter in Bell.

“It was different dating someone who looked really normal, but slowly learning that he’s adjusting to life as a whole different person,” Song said during a brief interview.

Harris would vanish for four or five days without warning. That’s how he cleared his head. He loved to drive. Arizona. Nevada. The destination didn’t matter.

Harris worked security with Alataua Lilo at underground parties in L.A. for $25 an hour to supplement his job at the event management company. Even then, Harris dropped out of sight several times. He’d resurface with mysterious stories for Lilo about going on cruises (he wouldn’t say where) or meeting women (he never mentioned names or ages).

Sure, Harris could break up a fight with one push from his giant arms. But Lilo thought of him as a 300-pound teddy bear, maybe a little timid at first, a little slow to laugh at a joke. But Lilo couldn’t find a more loyal employee.

Lara noticed his friend grinning again, laughing, focused on the security career. But he wondered if Harris had traded one addiction for another, if work became a drug.

The same question nagged Song, but the relationship moved forward. They discussed having children. But he didn’t want them to experience the same pressure he felt playing basketball.

“He saw all the bad in it,” Song said.

::

They replay their last conversations with Harris, searching for clues. They wonder if a different word, a different reaction could’ve changed what happened.

Harris called while Lara parked at Disneyland. Harris said he had a rough couple of months, struggled with depression, started drinking again.

“He was a man who had been broken by many things, by life’s general weight, by the weight of dreams unfulfilled,” Lara said. “I think he was a broken human being.”

Harris sounded jittery when he spoke to Lilo and kept apologizing for disappointing him.

He was a man who had been broken by many things, by life’s general weight, by the weight of dreams unfulfilled. I think he was a broken human being.

— David Lara, friend and neighbor of Harris since elementary school

“I’m sorry,” Harris kept repeating. “I didn’t want to let you down.”

Lilo didn’t understand what his friend was talking about.

Harris drove alone from Seattle to Alhambra on Oct. 8 to collect more clothes at his mother’s house for a job selling time shares. He sipped a beer with his stepfather at the duplex and wondered if moving was the right choice.

“I said, ‘Then why are you doing it?’” Charles Taylor said. “He said, ‘Well, I’m ashamed of the things that happened down here and I want to start another life.’”

As Harris pulled clothes from bins, Fernandez told him about her disappointment in the relapse to end seven years of sobriety. She urged him to pull it together. He agreed and apologized.

“Something broke in him to the point where he felt like his comfort was going to be in alcohol,” Fernandez said. “He needed to self-medicate to make himself feel at least some kind of joy.”

::

Not long after authorities found the empty Nissan, a family returning from Sacramento noticed a cellphone on the pavement next to the road about a mile south of the park. The battery was dead, but the phone didn’t appear damaged. A black backpack leaned against the guardrail next to the phone. Inside were jumper cables, a few pieces of clothing and two bottles filled with what appeared to be alcohol and an energy drink.

The family told Sgt. Dean Nyland, the lead detective in the case, they searched without success for an owner.

On the phone, Nyland found a video of Harris sitting in the car at the park. The camera faced the dome light. Music blared as Harris tore through papers in the glove box and flung them around. His wallet — including credit cards — landed in the back seat amid the mess of paper.

The Sheriff’s Aero Squadron airplane combed the valley. Authorities sent out more than 4,000 telephone and text messages to residents near the search area through a reverse 911 system. Nyland checked every phone call Harris made, every cell tower his phone interacted with, including the last call to his mother around 9:30 a.m. on Oct. 10 that ended with the usual “I love you.”

Four days after the search started, a deputy found tracks in sand by Cache Creek around noon that weren’t there earlier in the day. They weren’t distinct enough to cast. But the tracks didn’t come from an animal and were large enough to have been left by Harris’ size 18 feet.

The same day a driver noticed a large individual — the gender and dress weren’t clear — walking along State Route 16. It was one of several similar sightings that week.

Ten teams of cadaver dogs from a volunteer group explored the park. A dive team explored the water, including a small waterfall. Nothing. Near the end of October, authorities scaled back the search.

Nyland read hundreds of text messages Harris sent and received. Listened to his voice mails. Interviewed his friends and family.

“He didn’t have the rosy relationship with the girlfriend that she tries to depict,” Nyland said. “I think she was trying to make a better person out of him. She was trying to change Rico, maybe too fast. He’s a free-spirited person.”

Nyland visited the area around the park dozens of times. Walked it with his dog on days off. Even reenacted the 100-mile drive from Lodi, where Harris last filled up with gas, into the valley. None of it makes sense to the detective. There wasn’t any sign of a struggle or evidence of a crime. His best guess is Harris returned to the site, searched in vain for the car, then got a ride out of the area. Lara wonders if his friend’s trusting, mild-mannered disposition led him to let his guard down.

The case still bothers Nyland. But more than that, he’s haunted by Fernandez living without her son.

“There’s no way,” Nyland said, “you’re going to convince the lady you’re doing everything possible to find him.”

::

Even today, a quiet panic fills the mother each time her flip phone rings.

Every tip or would-be sighting of Harris leads to another dead end. There aren’t any answers or explanations, only Fernandez wondering if this phone call is the one that will finally bring resolution.

“This is a pain that’s deep, that goes down to your core,” she said, wiping away tears that keep coming. “It’s like you’re on a merry-go-round and can’t get off. Nothing is going to quiet the pain. Nothing is going to make it go away. ... He could be alive. Maybe he’s not. I don’t know what the truth is. I don’t know. People don’t just vanish.”

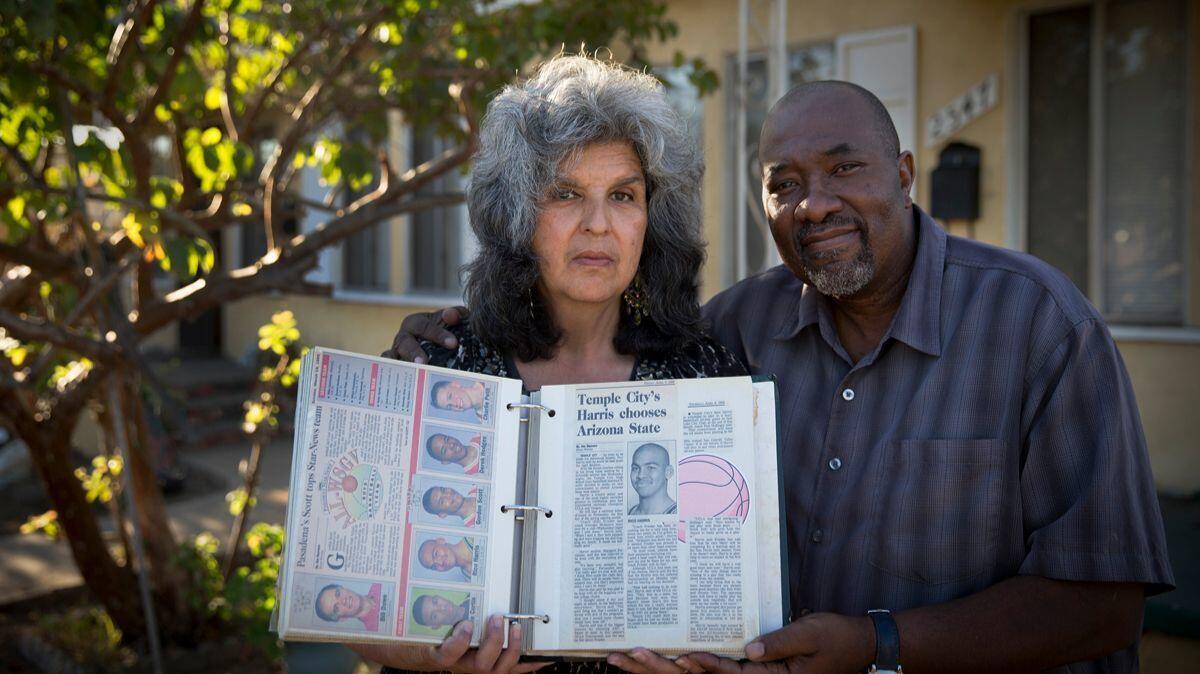

Fernandez keeps her son’s clothes in bins awaiting his return. She flips through thick scrapbooks filled with newspaper clippings from his basketball career, remembers the way he grabbed her shoulders and kissed her cheek, posts pleas on Facebook.

“Something sinister is lurking in that part of California.”

“Rico you are not forgotten ever.”

“I am not giving up on finding my son.”

Twitter: @nathanfenno

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.