Former MVPs wonder why Kenesaw Mountain Landis’ name is on the trophy

- Share via

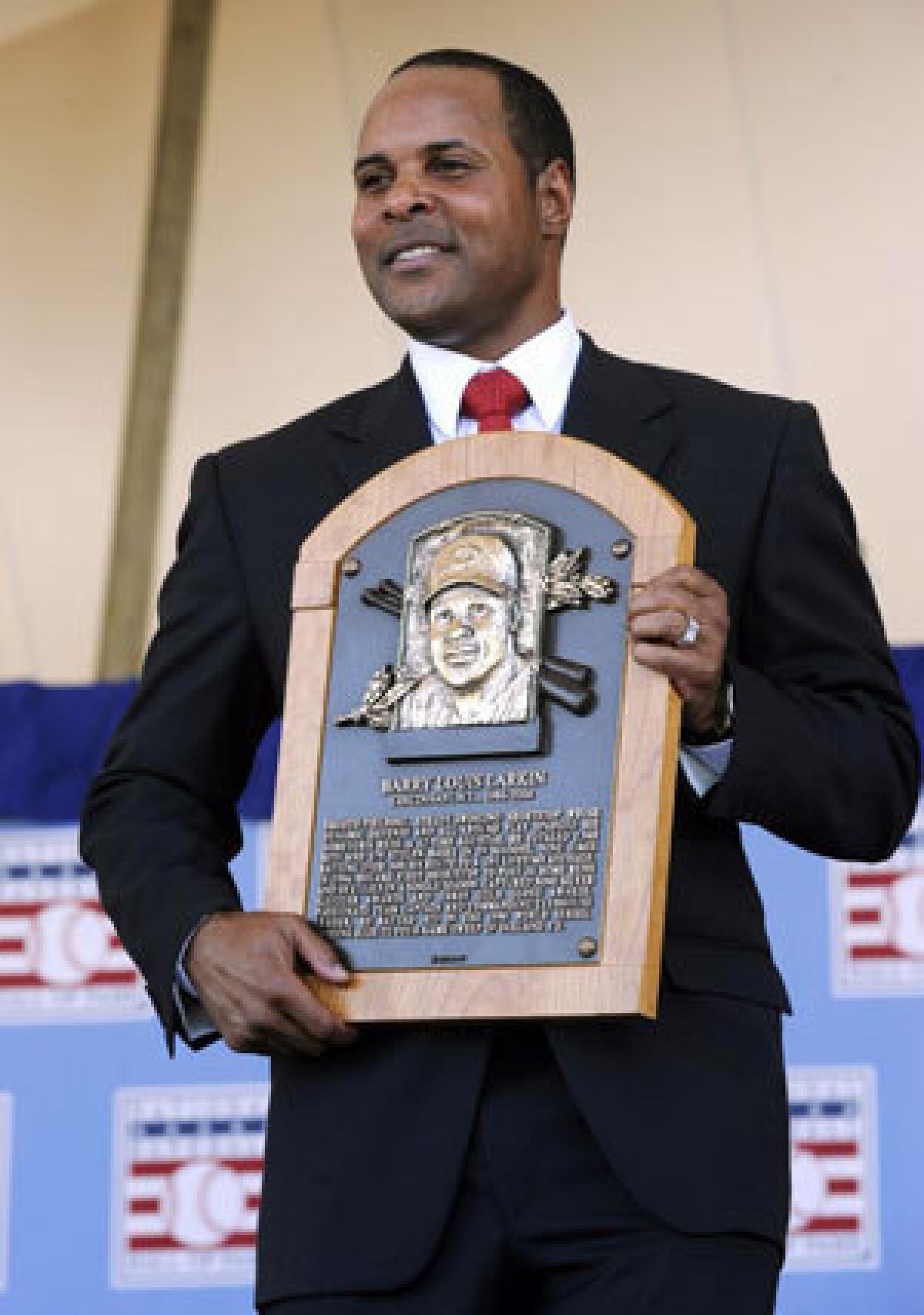

Something still bothers Barry Larkin about his most valuable-p\layer award.

The other name engraved on the trophy: Kenesaw Mountain Landis.

“Why is it on there?” said Larkin, the Black shortstop voted National League MVP in 1995 with the Cincinnati Reds.

“I was always aware of his name and what that meant to slowing the color line in Major League Baseball, of the racial injustice and inequality that Black players had to go through,” the Hall of Famer said this week.

Hired in 1920 as the sport’s first commissioner to help clean up rampant gambling, Landis and his legacy are “always a complicated story” that includes “documented racism,” official MLB historian John Thorn said.

This much is true, in black and white: No Black players in the majors during his quarter-century tenure. Jackie Robinson broke the barrier in April 1947, about 2 1/2 years after Landis died.

But there he is, prominently displayed on every American League and NL MVP plaque since 1944 — Kenesaw Mountain Landis Memorial Baseball Award, in shiny, gold letters literally twice as big as those of the winner.

As Ryan Braun prepared to leave his Malibu home Monday to return to Milwaukee for the restart of team training, he wasn’t sure how long he would be gone.

With a sizable imprint of Landis’ face too.

“If you’re looking to expose individuals in baseball’s history who promoted racism by continuing to close baseball’s doors to men of color, Kenesaw Landis would be a candidate,” three-time NL MVP Mike Schmidt of Philadelphia said.

Added 1991 NL MVP Terry Pendleton of Atlanta, who is Black: “This is 2020 now and things have changed all around the world. It can change for the better. Statues are coming down, people are looking at monuments and memorials,” he said. “We need to get to the bottom of things, to do what’s right. Yes, maybe it is time to change the name.”

During the 1944 World Series, the Baseball Writers’ Assn. of America voted to add Landis’ name to the plaque as “an acknowledgement of his relationship with the writers,” longtime BBWAA secretary-treasuer Jack O’Connell said.

A month later, Landis died at 78. He soon was elected to the Hall of Fame.

“Landis is who he is. He was who he was,” Thorn said. “I absolutely support the movement to remove Confederate monuments, and Landis was pretty damn near Confederate.”

Landis broke up exhibitions between Black and white All-Star teams. He invited a group of Black newspaper publishers to address owners in what became a cordial but totally fruitless presentation.

Toward the end of his tenure, he told owners they were free to sign Black players. But there is no evidence he pushed for baseball integration, either, as the status quo of segregation remained.

“If you have the Jackie Robinson Award and the Kenesaw Mountain Landis Award, you are at diametrically opposed poles,” Thorn said. “And it does represent a conundrum.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.