- Share via

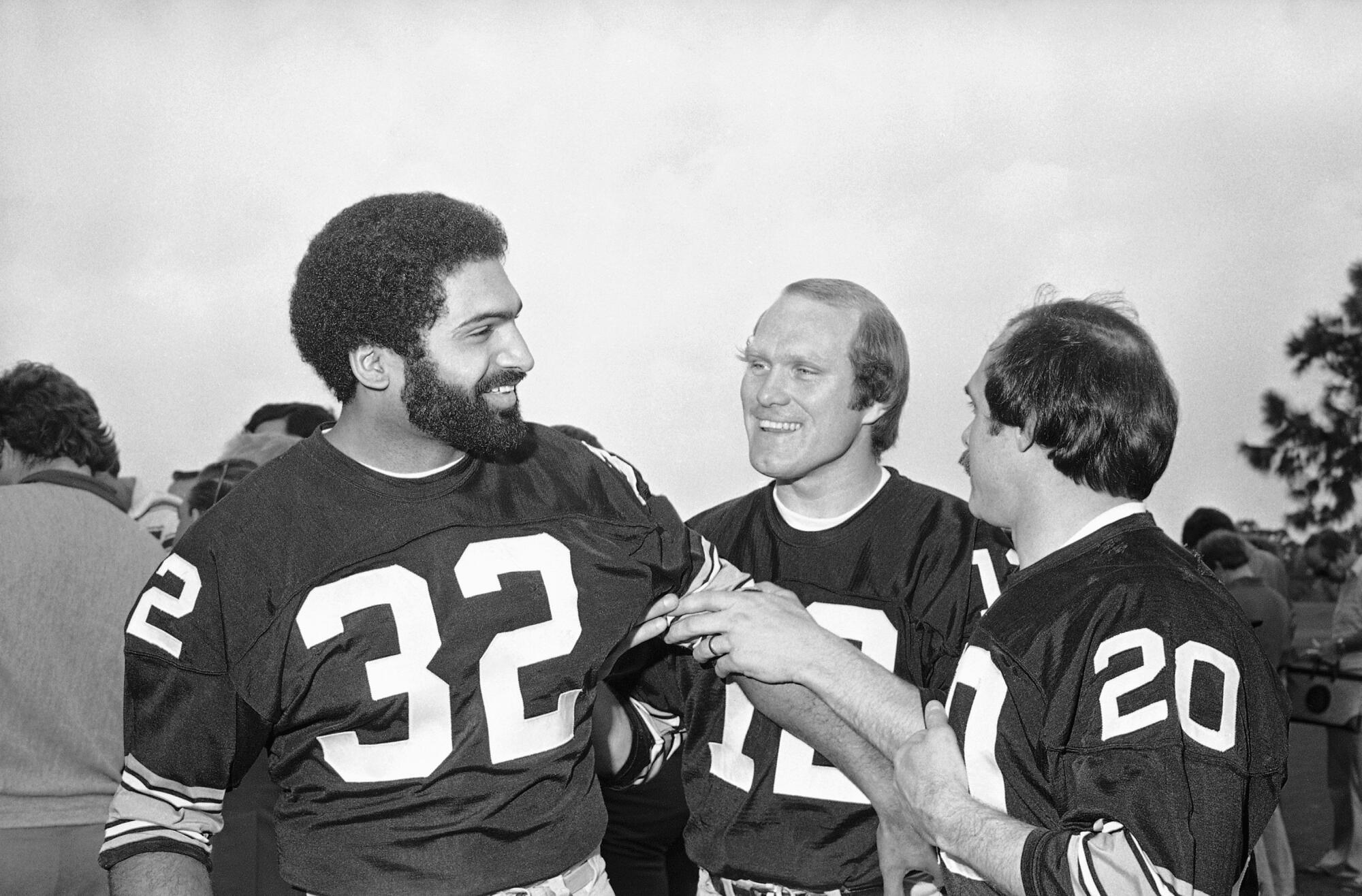

PITTSBURGH — When the Pittsburgh Steelers drafted Franco Harris in 1972, the franchise was best known for its futility. In its 40 years of existence, the team had never won a playoff game. It had played in only one playoff game, in fact. The Steelers were referred to as “lovable losers,” and some people would leave out the “lovable” part.

No reasonable person could have imagined that the Steelers would win four Super Bowls in six seasons, and eventually six championships in all; that the team would produce a slew of Hall of Fame players; or that the franchise would be recognized as one of the most accomplished in professional sports.

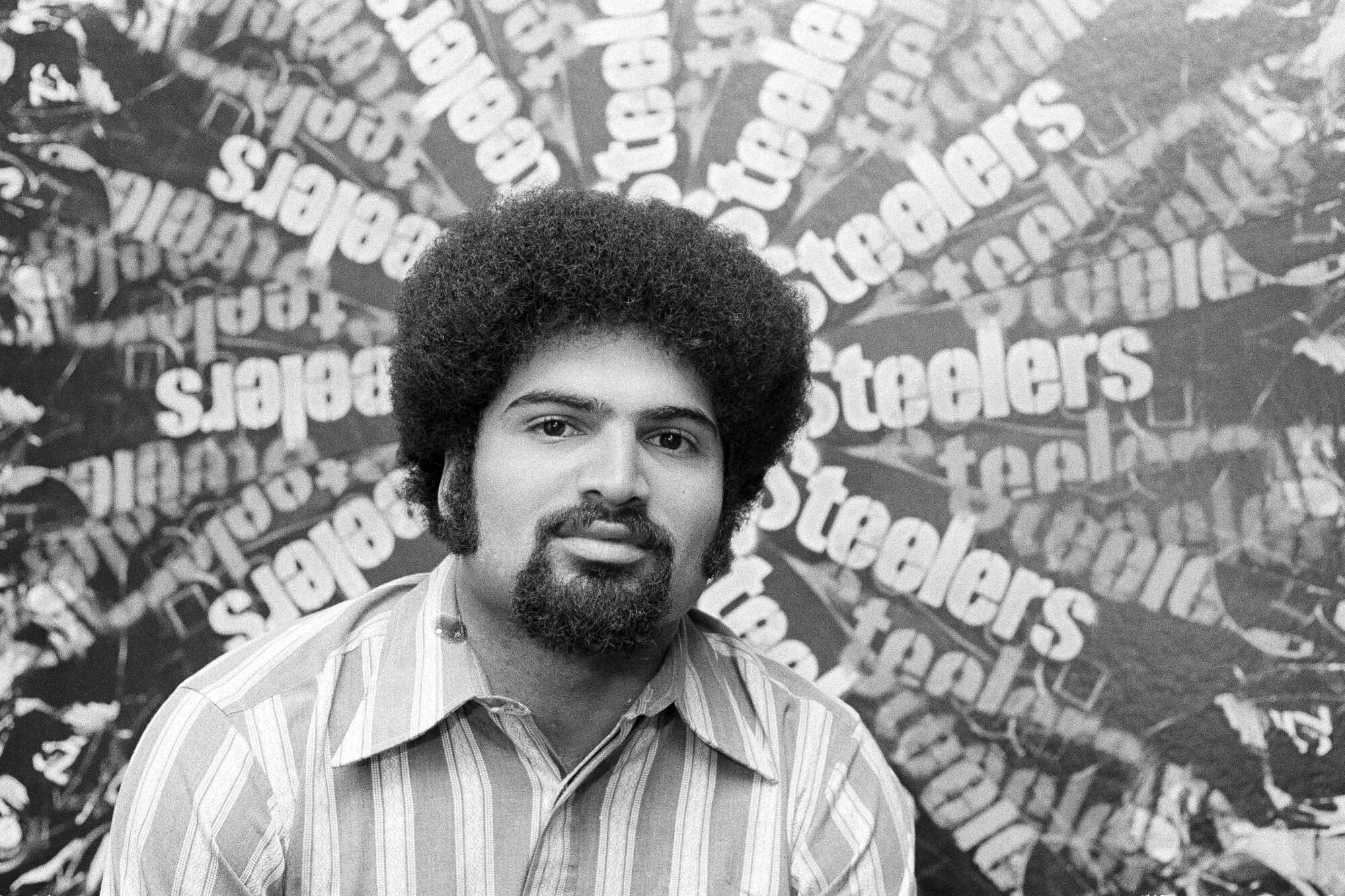

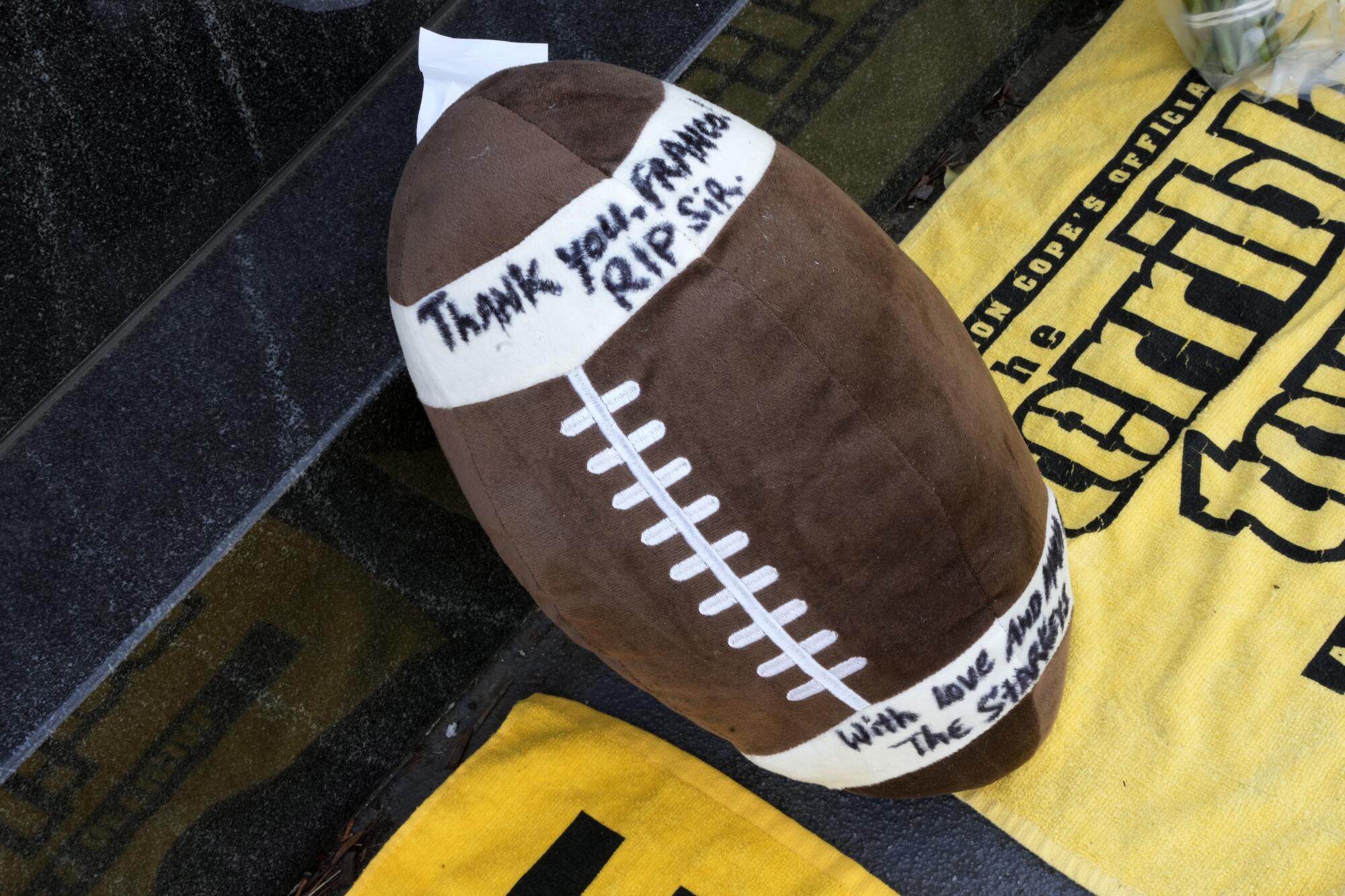

That’s one reason — although far from the only one — why Harris’ unexpected death at age 72, announced early Wednesday, shocked Pittsburgh and the pro football world. Harris’ name has been in the news of late because Friday was the 50th anniversary of the “Immaculate Reception,” perhaps the most famous play in pro football history and the event that launched Harris’ career and the Steelers’ climb up the NFL ladder.

Dec. 23 will mark the 50th anniversary of the ‘Immaculate Reception,’ Franco Harris’ famous catch in 1972 that changed the course of Steelers football.

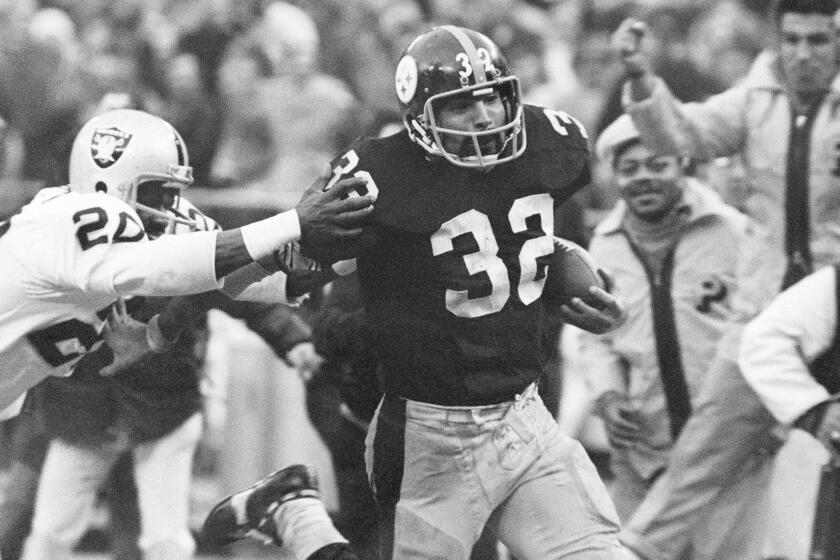

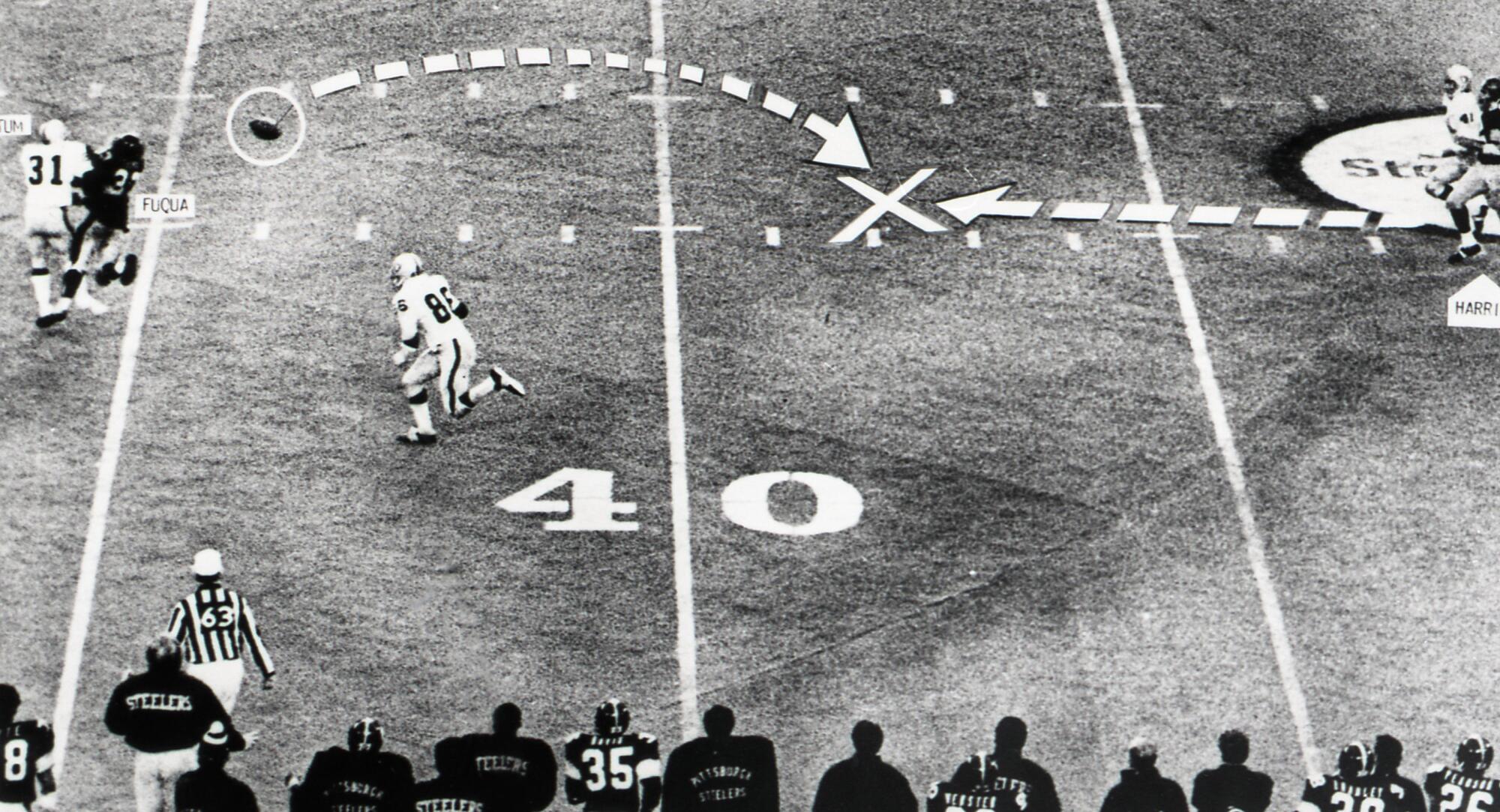

On Dec. 23, 1972, the Steelers trailed the Oakland Raiders 7-6 in the final minute of an AFC divisional playoff game in Pittsburgh. On fourth down with 10 yards to go, Steelers quarterback Terry Bradshaw threw a desperation pass toward running back John “Frenchy” Fuqua. Raiders safety Jack Tatum delivered a punishing hit on Fuqua and the football ricocheted back toward the line of scrimmage. Harris caught the ball when it was inches from the ground before running it into the end zone to score the winning touchdown.

NFL Network ranked the Immaculate Reception No. 1 on its list of the 100 greatest plays in league history, and the image of Harris stooping to grab the ball and then loping down the sideline is ingrained in the minds of football fans. But the play remains controversial, with the Raiders and others insisting the touchdown should not have counted.

Art Rooney II, the Steelers’ owner and president, and grandson of Steelers founder, Art Rooney Sr., said last month that although the team had started building a winner by 1972, the running back’s arrival was a key piece of the puzzle.

“My grandfather always said that Franco had a knack for performing well in the biggest games,” Rooney said, “and the Immaculate Reception was the first of many examples.”

I emailed the Steelers’ public relations department a few weeks earlier and asked whether Rooney might be available for an interview, explaining I was working on a story about the Immaculate Reception and the upcoming anniversary. I also asked whether the staff could put me in touch with Harris, the central figure in the amazing play.

The Steelers said they would pass my request along to Harris’ wife, Dana, who handled his interview requests, and a few days later I received a message from her saying her husband would talk with me. We eventually found a day and time, working around Harris’ busy schedule of business meetings, charity work and ambassador work for Pittsburgh and the Steelers. I had hoped I’d be able to talk with Harris for 20 minutes, but we ended up chatting for almost an hour.

Although he clearly enjoyed recounting his key role in the Immaculate Reception, Harris spent just as much time discussing his Steelers teammates from the 1970s and the Steelers’ fans.

“We didn’t talk about the Immaculate Reception that much for the rest of the ‘70s,” he said of his teammates. “We played in a lot more big games and we were usually living in the moment. But once we retired and it was over, we began to look back and you gravitate toward certain moments, and that was a big one.

“To me, that game was the birth of Steelers Nation. There was a different feeling, an aura, about the Steelers after that. We’ve had an incredible following. It really has been special.”

People in Pittsburgh loved Harris back from the beginning. In his rookie season, a fan club formed that called itself “Franco’s Italian Army.” The founders latched on to Harris not only because of his skill at running with a football, but because his mother was from the old country.

A little more than a week before the Immaculate Reception, the Steelers were practicing in Palm Springs to prepare for their final regular-season game, against the Chargers in San Diego. At a restaurant one night, some Steelers officials noticed that one of their fellow diners was perhaps the most famous Italian American of them all, Frank Sinatra.

Legendary Pittsburgh sportscaster Myron Cope — later the creator of the Steelers’ Terrible Towel — was enlisted to slip a note to Sinatra. In the note, Cope explained Franco’s Italian Army and invited the singer to the Steelers’ practice the next day. Sinatra went to the practice, met Harris, was inducted into the army with the rank of general and received one of the group’s helmets.

“Not only did I get to meet Frank Sinatra,” Harris said, “but after the Immaculate Reception game, he sent me a telegram to congratulate me. How cool was that?”

Phil Villapiano, the former Raiders linebacker who had been covering Harris just before he made the famous catch, met Harris when the latter was in college. Harris had been voted the Italian American player of the year and Villapiano had won the award the year before.

“I met him at the banquet they had, and we discovered that my dad and his mom were from the same area in Italy and they spoke the same dialect,” Villapiano said.

Despite the heated rivalry between the Steelers and Raiders, Villapiano and Harris became friends while playing together in the Pro Bowl four times and remained close throughout retirement.

“We were good friends and we just talked about the usual stuff that guys talk about,” Villapiano said. “But we had the memories of the NFL and that was special. That was something that we shared.

“He helped me in business so many times. He was a beautiful person, very humble. I’m going to miss him dearly.”

“As much as he contributed on the field, he contributed even more to the community off the field. He was the Pied Piper. People gravitated toward him because he was such a special person. Even among all of those Hall of Fame players on the Steelers, he was a leader.”

— Joe Gordon, former Steelers public relations director

Joe Gordon, who was the Steelers public relations director from 1969 to 1998, knew Harris for five decades and had lunch with him from time to time. He said Wednesday news of Harris’ death was “crushing.”

“Our friendship was very special,” Gordon said. “During the pandemic, he would call every two or three weeks to make sure my wife and I were doing OK. And there were probably 20 other people he did that for.

“As much as he contributed on the field, he contributed even more to the community off the field. People gravitated toward him because he was such a special person. Even among all of those Hall of Fame players on the Steelers, he was a leader.

“There’s a huge hole in Pittsburgh today, that’s for sure.”

Harris’ loss is also being felt in State College, Pa., where he starred for Penn State in the early 1970s. Jay Paterno, son of longtime coach Joe Paterno and a former assistant coach with the Nittany Lions, said he has long respected Harris and that it has little to do with football.

“When you admire someone from a distance, and then you get to know them and they exceed your expectations, it’s special,” Paterno said. “He was gifted and when he had an opportunity to make that play, he was prepared and he took advantage of it. But what he did with that, the life he led and his service to others, it’s an example for all of us.”

Paterno said that Harris’ friendship helped fill a void in his life after his father died in 2012.

“I came to admire him even more during that time. His loyalty to Penn State and his loyalty to my family during some difficult times is something that I’ll never forget,” Paterno said.

As I was wrapping up my interview with Harris last month, I congratulated him on the Steelers’ upcoming retirement of his No. 32 jersey, scheduled for Christmas Eve, and mentioned a mutual friend of ours. I also thanked him for his time and told him I enjoyed our conversation.

“I did too. Thank you for writing this story,” he said. “Maybe we’ll run into each other around town sometime.”

I told him I hoped we would.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.