Separated from the myths, Sam Cunningham’s story remains an inspiration

- Share via

Several years after Sam “Bam” Cunningham helped an integrated USC football team whup an all-white Alabama team in 1970, Cunningham traveled to Montgomery, Ala., for a golf tournament.

The locals wanted to talk about the game.

“I remember when you scored 250 yards and scored four touchdowns!” they said.

Cunningham was confused.

“Was that the same game I played in?” Cunningham said.

In the 46 years between that matchup and a rematch on Saturday in Arlington, Texas, the 1970 game has only grown in the retelling. It has now assumed almost mythic status.

Central to the legend are three tenets of unknown origin. First, that Paul “Bear” Bryant, Alabama’s longtime football coach, asked USC Coach John McKay to come to Birmingham, Ala., and pummel his Crimson Tide team, to teach the segregationists a lesson.

After USC did pummel his team, the legend goes, Bryant invited Cunningham into Alabama’s locker room and marched him in front of his players.

“This,” Bryant declared, “is what a football player looks like!”

Last, the game and the aftermath were said to directly wipe out segregation’s last stronghold in major sports — Southern football — and escort Alabama from an era of racial violence into a more harmonious time.

“Sam Cunningham did more to integrate Alabama in 60 minutes that night than Martin Luther King had accomplished in 20 years,” stated a famous quote, years after the game, attributed by different sources to Bryant or an assistant.

All three pillars of the story paint a portrait of larger-than-life heroes and rapid racial reconciliation. Problem is, all are demonstrably embellished, or just false.

“It’s already a historic story without adding sauce to it, you know what I mean?” Cunningham said. “Everybody wants to make it more than what it is. And what it was was very, very important anyway.”

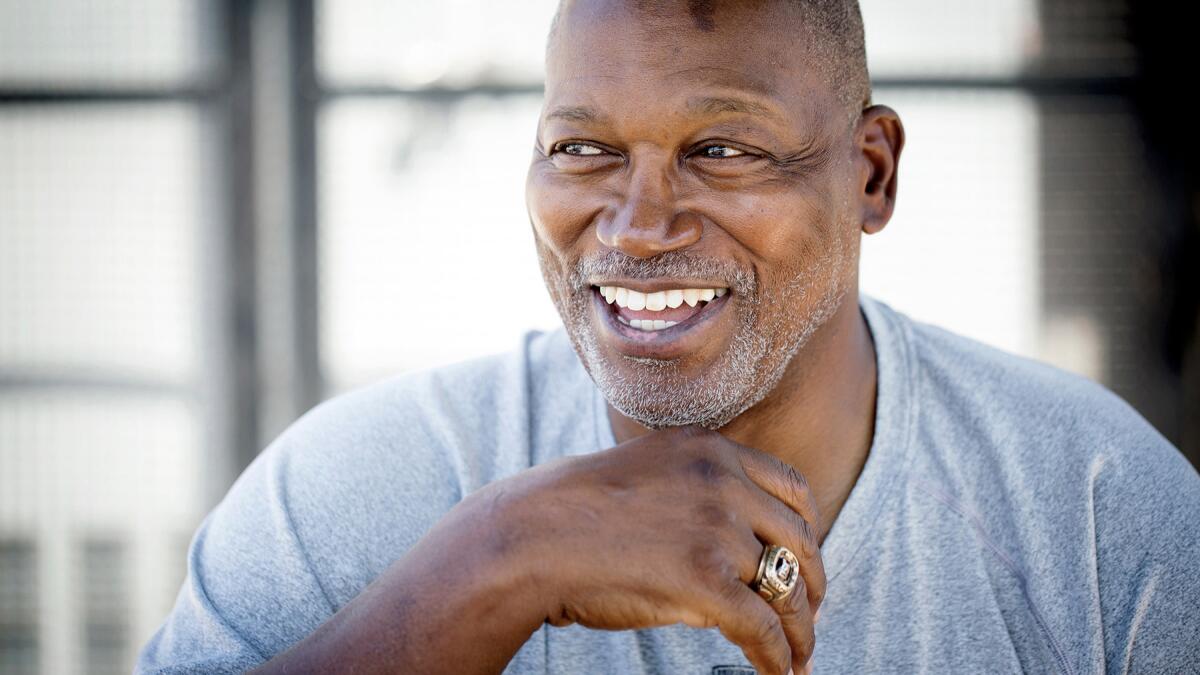

Cunningham, who after college went on to a long NFL career, was recounting the game over coffee and a bagel Wednesday on Los Angeles’ Westside. He wore tinted eyeglasses and blue jeans, with a pen clipped to the collar of his shirt, and had a thin, graying beard.

“After 45 years, it gets to be a little much,” he said. “I’ve heard pretty much every story. Even from people who actually went there and saw the game.”

Then Cunningham shared what he viewed as the messier, more authentic and equally inspiring story.

Bryant did indeed hatch the idea for the game. But, said Ken Gaddy, director of the Paul W. Bryant Museum in Tuscaloosa, Ala. said, “I don’t think there was any intent for it to be part of any grand scheme.”

J.K. McKay, John McKay’s son, rejected the idea that Bryant was trying to lose, though both coaches hoped for segregation’s end.

Some USC players, who had grown up in the South, packed knives for the trip, just in case. One brought a gun. But Cunningham, who’d grown up in Santa Barbara, focused on his job. Most of the California-born players, he said, paid little mind to the racial issues.

When USC landed in Birmingham, a large, white crowd greeted the team. Its members were curious but respectful. The team bus, heading to the hotel, drove past a black neighborhood, where the residents cheered. At the hotel, some teammates interacted with the gawking locals.

A curious group of kids knocked on the hotel door of Kent Carter, a black linebacker, wanting to see a black player in person.

“One of the boys walked over and touched him,” Carter’s roommate, John Papadakis, told the Times in 2000. “Kent took his hand, ran it down his face and said, ‘Black is beautiful.’”

When the game began, USC quickly realized it was vastly superior.

“Our spring practice was tougher,” Cunningham said.

USC won, 42-21, after McKay subbed in his backups in the third quarter.

Cunningham rushed for 135 yards and two touchdowns on just 12 carries, numbers that require no exaggeration, considering it was his first collegiate game. Bryant offered his congratulations, but he did not ever take Cunningham into Alabama’s locker room. That notion, he said, borders on absurd.

The game shocked Alabama fans unaccustomed to losing. But it was not the first time ’Bama had lost badly to an integrated team — Tennessee had defeated the Crimson Tide the previous season.

And Bryant had already recruited a black player, a freshman who wasn’t yet on the active roster only because NCAA rules deemed freshmen ineligible.

“That didn’t change how those white people thought of black people,” Cunningham said. “They were accepted because they could help their program win football games.”

The game did exhibit a triumph of equality over hate. It featured a courageous group of black players, able to execute their jobs faithfully in a city that treated their race with violence.

And it did provide a final push for integration, proving emphatically that segregation and football success couldn’t coexist. Bryant received little pushback afterward when he recruited more black players.

Why, then, has the story needed embellishment?

“Everyone wants it to be black and white, one day you flip a switch and things change,” Gaddy, the Bryant Museum director, said.

The real racial dynamics were more complicated. USC was not a colorblind utopia, either. The Trojans finished a mediocre 6-4-1 in the 1970 season. Cunningham explained that the black and white players could be tentative and awkward with each other, though they finally jelled by 1972 and won the national championship.

Cunningham is appreciative of the attention.

“I’m just proud to be a part of it, because it was such a special game,” he said.

The game, he said, did have a significant impact on Southern athletics. It did inspire black children in Alabama, like those USC’s bus drove past, who’d always felt excluded.

Change, though, didn’t require any heroes.

“We’re just regular people,” Cunningham said. “I didn’t do anything more than what I was asked to do. Run the ball. If there’s a hole, run through it. If you can score a touchdown, score a touchdown. Bam. Pretty simple to me.”

The real Cunningham, separated from myth, moved on and lived a normal life, full of mundanities and little bursts of humor. He will be USC’s honorary captain Saturday. He mentors students at local schools. He started his own landscaping business, A&T Landscaping.

The name, on a whim, came from the two hamsters he owned when he played in the NFL, Astro and Turf.

He laughed sheepishly. The truth is strange sometimes, and every bit as rich.

zach.helfand@latimes.com

Twitter: @zhelfand

More to Read

Fight on! Are you a true Trojans fan?

Get our Times of Troy newsletter for USC insights, news and much more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.