Eight sides to this story

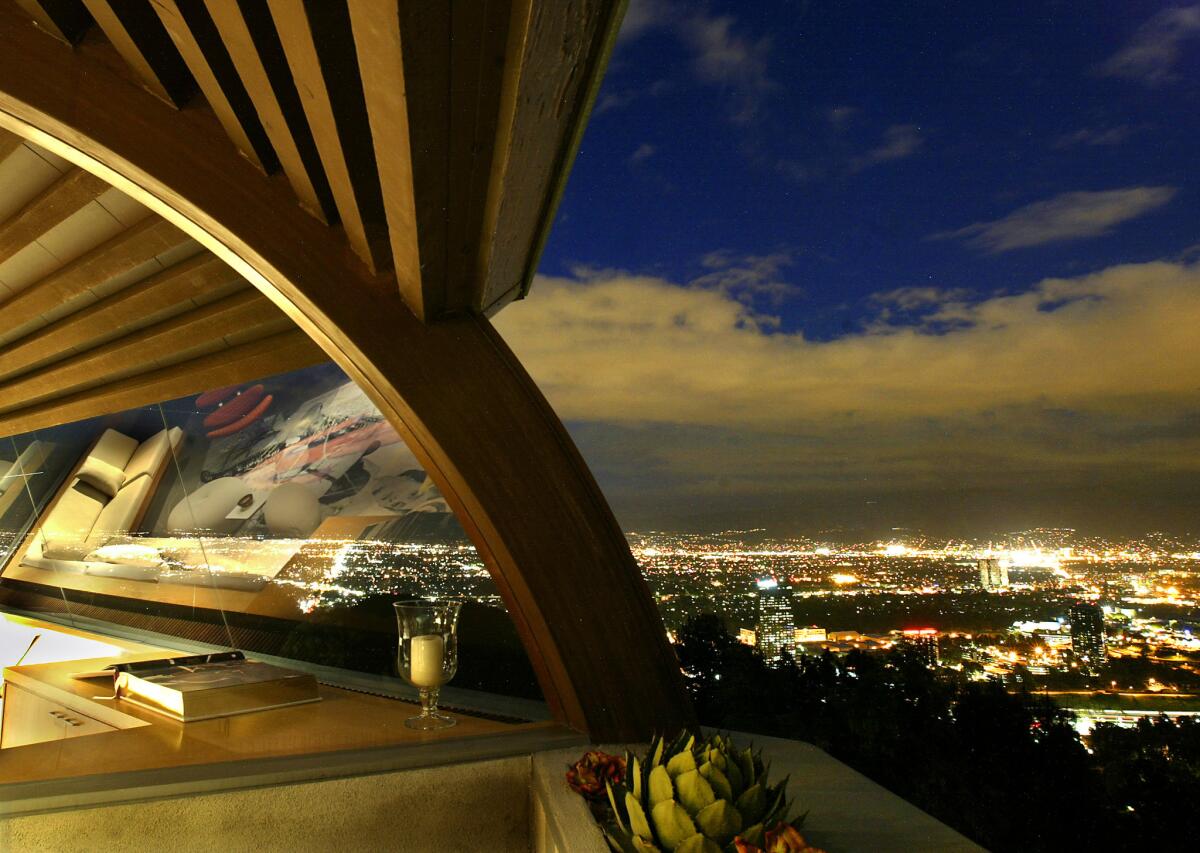

Chemospheres glue-lam beam construction offers panoramic windows on the Valley.

- Share via

When Benedikt Taschen, a globe-trotting publisher of stylish art books, and his then-wife first laid eyes on Chemosphere House in 1997, the iconic Los Angeles structure had seen better days.

The sleek, octagonal house, perhaps the boldest work by the singular architect John Lautner, is considered a masterpiece of California Modernism and is beloved by cultists of midcentury design.

But the Taschens saw dirty, disco-era, wall-to-wall carpet on much of its 2,200 square feet, an old aluminum door, smudged windows and seven layers of paint on what was originally a gently austere, exposed brick wall.

Still, “it was love at first sight,” says the laconic German, wearing a red Muhammad Ali bathrobe as he shows off the place on a hazy morning. The backlist of Taschen’s company — from homoerotic nudes to the original Lutheran Bible — includes books on Modernist homes, the architectural photographs of Julius Shulman and monographs on Richard Neutra and the Case Study houses. Some of the books, along with dozens of art magazines, are scattered around the house and its unobtrusive furniture.

Today, the place is serene and airy, with a simple, light-wood openness that suggests midcentury Scandinavian crossed with a ski chalet, and views that are pure Southern California.

“I bought it right away — as fast as possible,” says Taschen.

Frank Escher, who was brought in as restoration architect, vividly remembers the place’s condition. “I have to give Benedikt credit for seeing past the disrepair and sad state the house had fallen into,” he says. “It looked like a rundown motel. It had been rented out for 10 to 12 years; it was like the ultimate party house.”

In fact, during much of that decade, the place had been on the market. “It was for sale for so long,” says Taschen, “that it was even in a ‘Simpsons’ episode: a house with a for-sale sign.”

“There was no market for that house,” says Julie Jones, the Realtor in the sale, who had watched the place languish after she listed the house. “Everybody loved Spanish, and then shabby chic came in.” Midcentury houses “would sit and sit and sit — you couldn’t give ‘em away. People would want to see the view, and that was about it.”

The fate seemed unjust for a structure the Encyclopedia Britannica had once judged “the most modern home built in the world,” and which had appeared in Brian De Palma’s “Body Double.” It’s hard not to see the house, which sits on a 29-foot-high, 5-foot-wide concrete column over a long-considered-unbuildable Hollywood Hills site, as a hovering flying saucer or a prototype for the 23rd century architecture of “The Jetsons.”

But the 1960 house is very much a work of its time and place.

Alan Hess, an architectural historian and author of “The Architecture of John Lautner,” considers Chemosphere as perfect an expression of Southland culture as Greene & Greene’s Gamble House, Eames House and the finest work of Neutra and R.M. Schindler.

Chemosphere was characteristically Los Angeles of that time because “it didn’t have to look like a house,” says Hess. “It was an architecture newly defined. It could take on its own brand-new shape. It displays the optimism of its time: that technology can be used to solve any problem, just as Century City and Googie’s,” the Lautner-designed Sunset Boulevard coffee shop, did. “The West would not be possible without technology: Water, electricity, everything that it took to overcome dryness and distance was dependent in some form on technology.

“Something I find fascinating about the house is that it is a single-family home,” built for a couple and their four children. “And yet whenever that house is used in the movies, it’s always a decadent bachelor pad. You have the reality of Southern California life, and the image of Southern California life, summed up in one house.”

It’s not the only contradiction the place contains. “From the outside it looks like a spaceship which you cannot enter,” Angelika Taschen says from Berlin, where she now lives. (The couple are finalizing a divorce.) “But if you go inside, it feels very cozy … very Zen and calming. Maybe because you are floating above the city, above reality in the sky. You feel disconnected from the planet and completely free and happy.”

The house is the product of a fortuitous union of architect, client, time and place. Leonard Malin was a young aerospace engineer in late-1950s L.A. whose father-in-law had just given him a plot north of Mulholland Drive, near Laurel Canyon. The land was leafy and overgrown, with extravagant views of the San Fernando Valley.

“My philosophy at the time was, most people work their whole lives to build their dream house,” Malin says from Arizona, where he’s constructing a new home. “Why not build it now, and pay for it for the rest of my life?” This was a time, during L.A.’s postwar expansion, when a middle-class client could build in the Hollywood Hills on a modest budget: Malin had $30,000 to spare.

The only catch: At roughly 45 degrees, the slope was all but unbuildable. The plot may have remained empty had Malin not approached Lautner, whose work he knew from a nearby house. Lautner, a brilliant but reputedly prickly man, sketched a bold vertical line, a cross, and a curve above it. “Draw it up,” he told his assistant Guy Zebert.

Though Lautner could appear imperious, a quality he may have learned from his mentor Frank Lloyd Wright, he was also a deeply practical and hard-headed problem-solver. Lautner didn’t see the house as a flying saucer but as a sensible solution.

However counterintuitive the scheme, it was also one of very few imaginable that allowed the plot to be utilized. And because of a concrete pedestal, almost 20 feet in diameter, buried under the earth and supporting the post, the house has survived earthquakes and heavy rains. (The house is reached by a funicular.)

“What was great about Lautner,” says Benedikt Taschen, “is that he had this dualism about nature and the city. On the other side, it’s very quiet,” he says of the home’s northern edge, which contains the bedroom and his office. “It’s pure nature, with all kinds of animals: skunks, bobcats, coyotes, deer. They are not shy; you almost have nose prints on the window.

“And here,” Taschen says, walking toward the living room window that faces the Valley’s homes and skyscrapers along the 101 Freeway, “it’s all city.”

Taschen admires the bold dichotomies the architect worked with. “That’s the characteristic of great artists: They can make things simple.”

Hess points out that Lautner’s embrace of Modernist innovation and organic forms made him a more interesting architect, but also contributed to his obscurity during much of his career. During the 1950s and ‘60s, the starker, cooler Modernism of the Bauhaus and of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe reigned in intellectual circles, especially in Europe and on the East Coast.

“Organic Modernism was just as modern in its use of materials,” Hess says, “but it had a different sense of space, which was flowing. The way a building was put together was like a tree or a flower or a cave — natural forms. Wright was one of the founders of that approach to Modernism, and Lautner brought it to Southern California.”

Even out-of-state critics and scholars who could appreciate the sharply angular California Modernism of midcentury didn’t know what to make of Lautner’s merging of the modern with natural forms. “So they ignored him,” says Hess, “or put him in the category of undisciplined, far-out, do-whatever-you-want California architecture.”

Escher, the preservation architect, considers Lautner “the missing link between the classic Modernism of the Case Study Houses and the work we now associate with Los Angeles — the more expressive, more sculptural forms. Frank Gehry has said that as a student, he considered Lautner to be a god.”

Unlike a lot of the more didactic and theory-driven homes of Modernists from Le Corbusier to Philip Johnson, it’s actually pleasant, most of the time, to live inside a Lautner. The homes don’t force their inhabitants into an ant farm’s existence the way some houses do. Le Corbusier called his homes “machines for living in,” and sometimes they felt that way, with their narrow hallways and rigidly prescribed paths.

Chemosphere is bisected by a central, exposed brick wall with a fireplace, abutted by subdued seating, in the middle. One side of the house is public, with a small kitchen and blended living and dining rooms including built-in couches below glass windows. The house’s private half includes a master bedroom with bathroom, small storage and laundry rooms, an office made of two children’s bedrooms, and an additional bathroom. Despite being more compact than many new single-family houses, it has most of the essential elements.

Angelika Taschen, a leonine PhD in art history, knew the house from Shulman’s photos before she saw the real thing. She worried it might be difficult to live there.

She said that besides limiting her trips out of the house because of the funicular, living there didn’t alter her behavior. “Day-to-day life is really easy,” she says, often easier “than in a conventional home where the architect has not thought so much about every single detail.”

Lautner, despite his reputation as having a strong personality, worked hard to suit his clients and their inner lives.

Angelika describes the place as having a spiritual impact, almost like a church. “With this house he found and expressed this almost religious spirit with a perfect architectural language in general, but also in detail.”

Benedikt likens the house to an eagle’s nest. “You feel safe. It’s warm and human, not a cold place. You would not expect it from outside.”

The only consistent problem with the house, Taschen says, is that its technology often fails in subtle but frustrating ways. “Every day there is something not working,” he says. “The maintenance is 10 times higher than in any other building. Everything is much more complicated. To get cable or Internet, they have to come 10 times.

“It’s like having a vintage car — a ’55 Mercedes. More difficult. But they have a personality to them, ya?”

In Escher’s first meeting with Taschen, the restoration architect pointed out which pieces were original, which needed to be replaced, and which details deserved restoration. “He interrupted me in about half a minute and said in German, ‘Herr Escher, why don’t you do what you think is right?’ ”

For Escher, a native of Switzerland who loves the rational, structure-inspired work of Lautner, Neutra and the late Pierre Koenig, this was a gift from the gods. His firm, which he runs with partner Ravi GuneWardena, had been partly inspired by classic California Modernism, and here he could delve into a great Modernist’s original conception. (Escher wrote the first book on Lautner a few years after moving to Los Angeles in 1988, and currently oversees the John Lautner Archives.)

The architect describes the job as a philosophical challenge. “I think the hardest thing was developing an intellectual strategy for how to deal with it,” Escher says, calling the task, “a combination of research into history and technology, and to some degree into Lautner’s psychology. You can’t be afraid of a house like that: You have to, in some cases, be kind of forceful.”

The forcefulness was balanced with the architects’ own “sensitive and careful” respect for Lautner’s intentions: The goal was to undo the damage previous tenants had exacted, and to simplify. The restoration team removed layers of paint, paneled the walls with the same shade of ash wood used for the original built-in couches and cabinets (some of which needed repair or restoration), and replaced the fixed-paneled windows with frameless glass.

“We wanted to make it as invisible and elegant as possible,” says Escher. “That’s something that’s important to all our projects: We don’t try to draw attention to a detail. It should disappear.” GuneWardena compares the process to “pruning a garden, to reveal the clarity of the structure.”

They also tried to match what they thought Lautner would have chosen if he’d had access to contemporary workmanship and a larger budget: The original drawings, for instance, described a floor of random broken slate, but the day’s technology would not allow the stone to be cut thinly enough to keep from destabilizing the house. Escher’s restoration ran the flagstone pattern inside and out, across the bridge that connects the front door to the funicular.

One of the biggest challenges was bringing art into the house, difficult when a home already exerts a bold personality. “The Taschens originally wanted to have more period pieces,” Escher says. “But we didn’t want the house to be a museum of the 1960s.”

Today, Chemosphere is furnished sparely with clean-lined pieces including Eames chairs and a coffee table and an oval Florence Knoll dining room table. Taschen commissioned the suspended lamps of bent plexiglass strips by Cuban-born L.A. artist Jorge Pardo and the pastiche rug designed by German painter Albert Oehlen.

“These Lautner houses are like custom-made clothes,” says Escher, “so you really have to find the right tenant for them. Taschen was perfect for the house — he immediately grasped what the house was about, and he was entirely open to our ideas for the place, like ripping out the glass and commissioning pieces by artists.”

During the first few years the Taschens lived there, the house became locally famous for their parties, where photographer Bill Claxton and his model wife Peggy Moffett would carouse with porn stars, jazz musicians and director Billy Wilder.

These days, now that Taschen has an office in Hollywood and a bookstore in Beverly Hills, the place has reverted to being, mostly, a house for him and fiancée Lauren Wiener. He has canceled plans for a guesthouse designed by Rem Koolhaas at Chemosphere’s base because he feared it would visually compete with the main house. His only major plan is to replace the bird-cage-like funicular with a more open one.

Taschen remembers going to a Beverly Hills open house where “a fashionable Hollywood film star” was selling his Neutra home. The young actor, in the publisher’s estimate, “had robbed the soul of the house. If you make tiny changes that don’t fit the integrity of the house, you destroy it. It’s like a movie where you add a scene of someone with a mobile phone in 1958, or a style of shirt or car that wouldn’t have existed until years later.

“It’s the responsibility of the owner to preserve it for future generations,” Taschen says, “because a house like this doesn’t belong to one or two people: It belongs to mankind.”

The Chemosphere restoration won an award from the Los Angeles Conservancy as well as the approval of its original tenant.

“Today there are materials that weren’t available then,” Malin says. “The place is much better than when I was in there — and it’s in keeping with Lautner’s vision.”

Taschen says it’s hard to get bored with the place — despite the rain this winter — since the enormous windows offer an expansive view on the world. “It’s like a wide-screen movie,” he says. “Always changing.”

Times staff writer Scott Timberg can be reached at scott.timberg@latimes.com.

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.