City Lights Bookstore has the true beat of San Francisco

- Share via

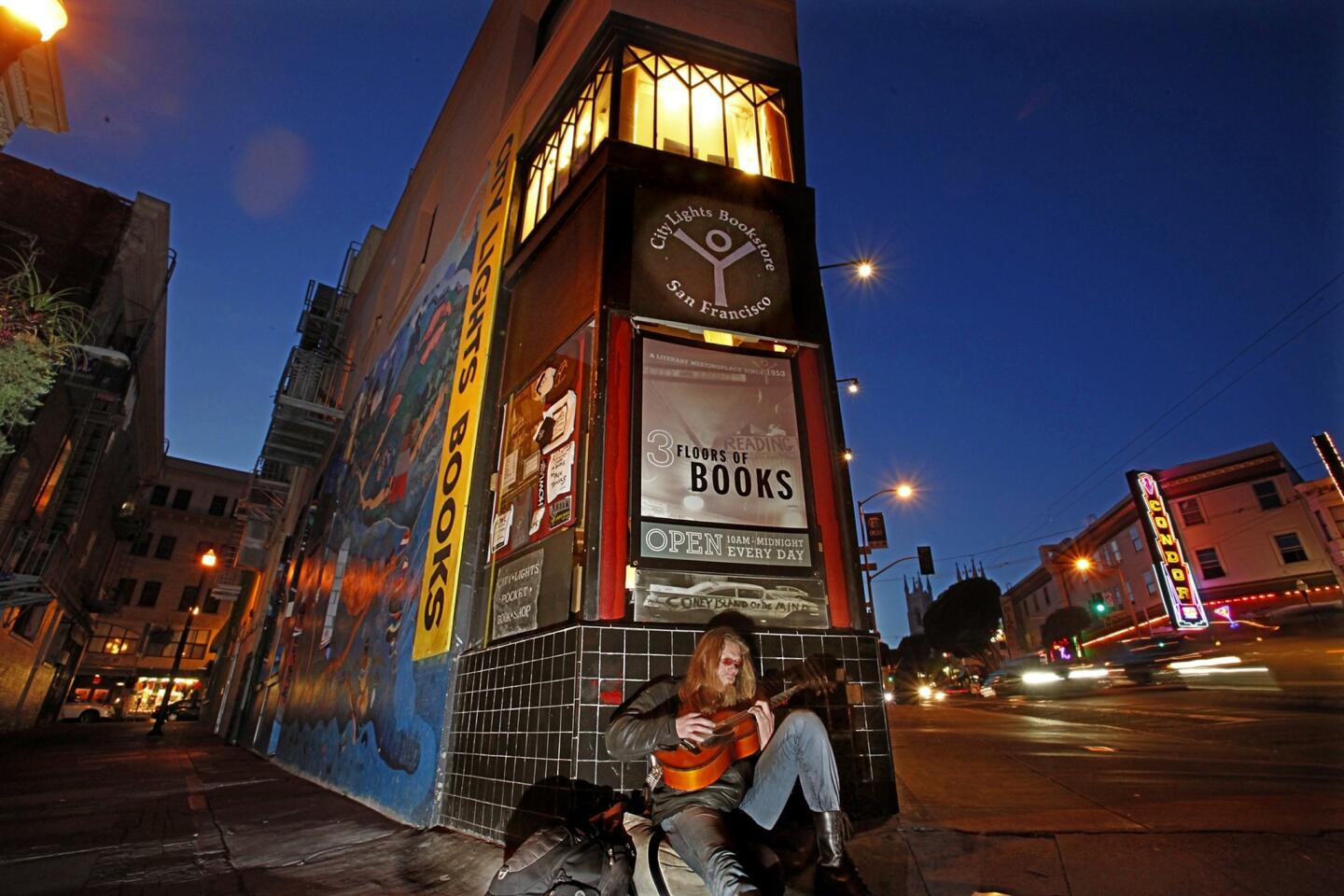

SAN FRANCISCO — To get to one of the spiritual centers of San Francisco — a perfect microcosm of the city of evergreen revolutions — turn left after the high-rising office buildings downtown, saunter past Francis Ford Coppola’s emerald-shaded seven-story American Zoetrope mock pagoda and halt just past the spot where Columbus Avenue meets Jack Kerouac Alley.

Or perhaps approach the official historical landmark by way of Grant Avenue, at the heart of San Francisco’s Chinatown, wander past a long line of slightly kitschy tourist shops displaying quotes from Lao Tse and Jimi Hendrix and try to ignore the eco-conscious green Hello Kittys in store windows.

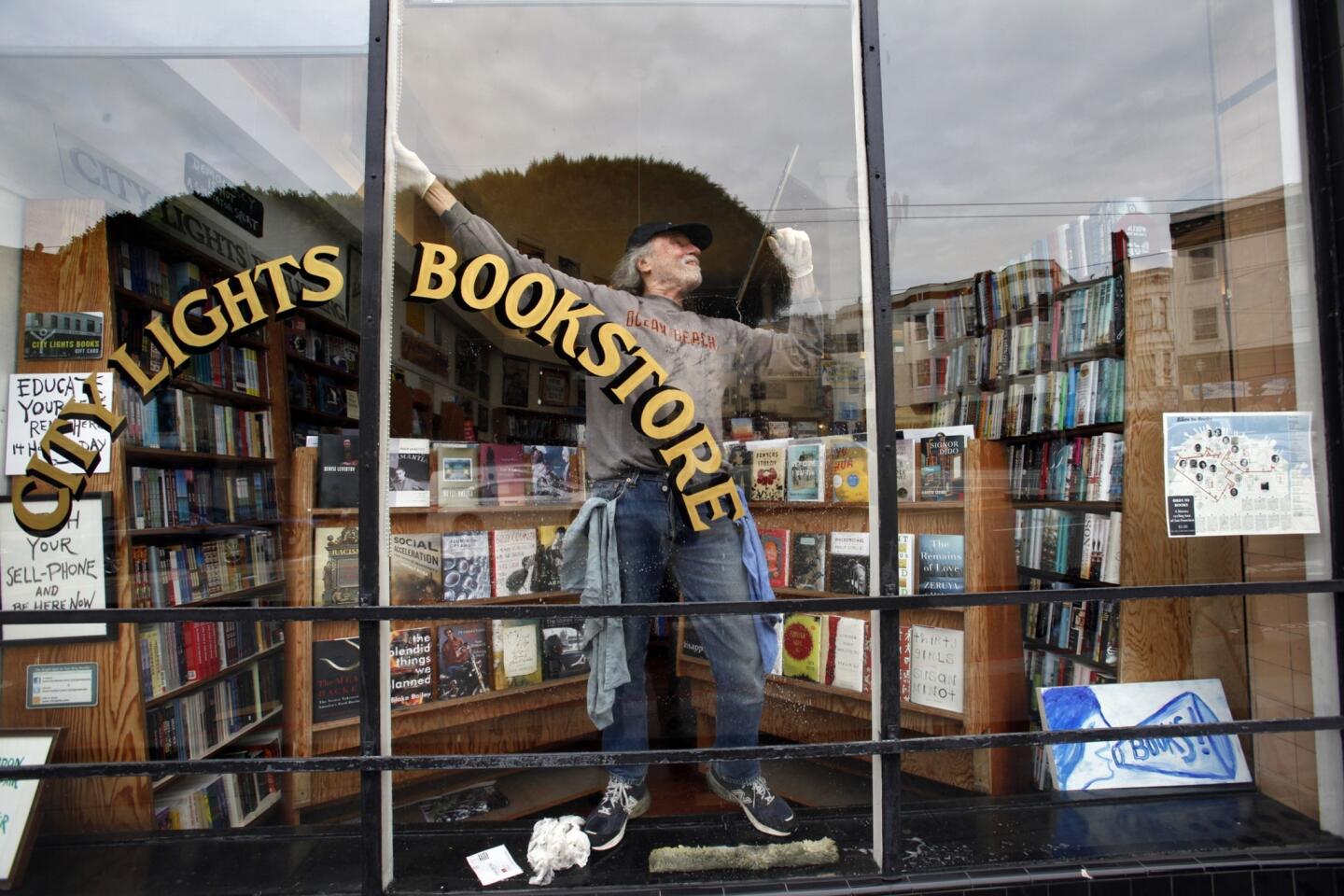

Out now onto busy Broadway, a raffish drag with Italian cafes on one side and tatty, once state-of-the-art topless parlors on the other, you find yourself in North Beach, an area (true to San Franciscan logic) not close to any beach at all. There, commanding a whole (tiny and irregular) city block, is the place that has for decades embodied and transformed the very notion of that endangered species, the independent bookshop. When I walked into City Lights Bookstore not long ago, I would have been surprised if the woman behind the cash register didn’t sport a shaved head, a leopard-skin pillbox hat (in tribute to Bob Dylan?) and two separate pairs of glasses climbing up her forehead.

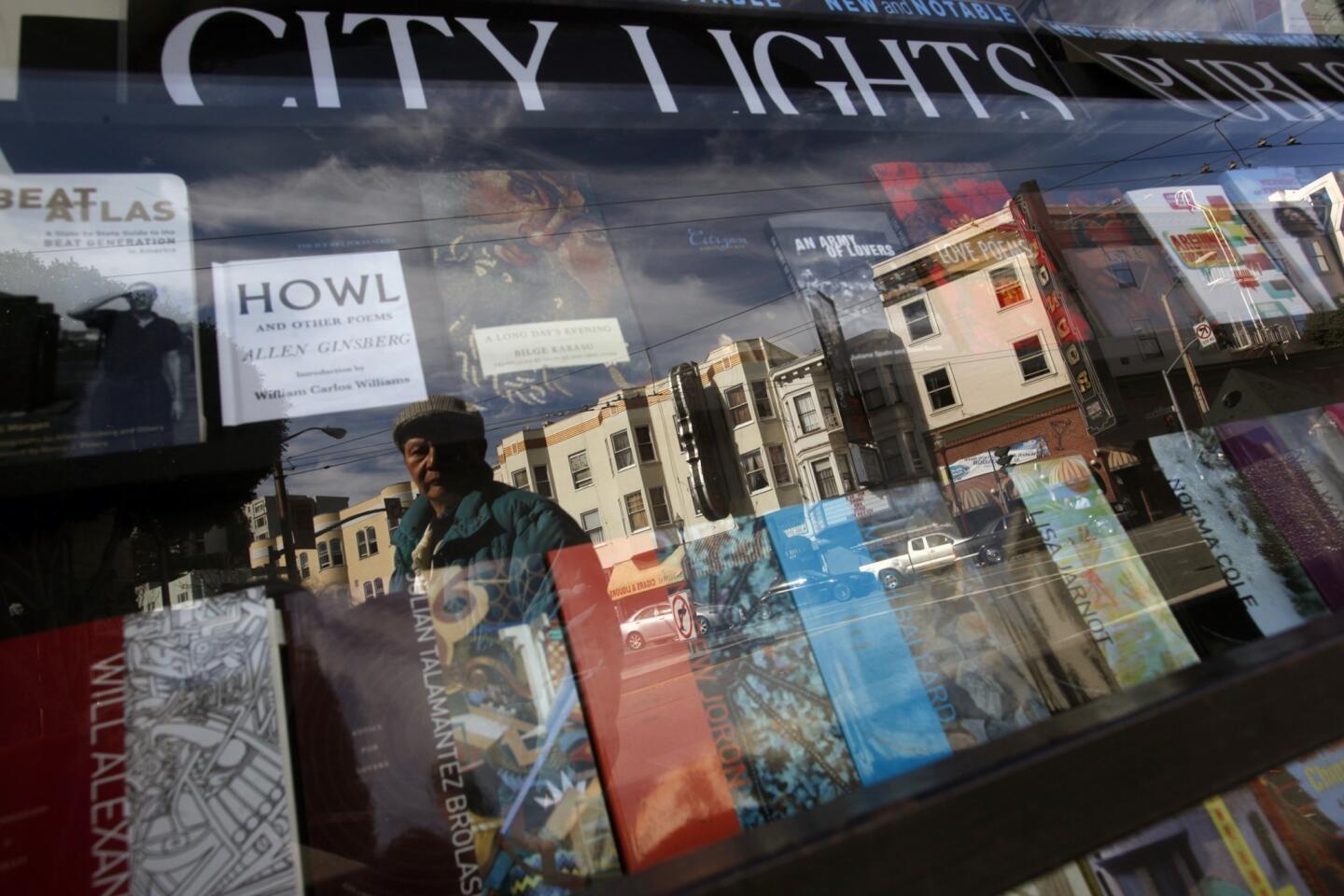

If San Francisco’s great tradition is the overturning of tradition, City Lights is one of its essential monuments, a literally triangular storefront that never begins to look square. The first volumes that greeted me were by André Breton and Antonin Artaud, celebrated mischief makers from more than half a century ago; every book displayed in the window, in fact, was at once highly serious and not to be found in any other shop window I could imagine. Very quickly you see that City Lights is a little like that ideal, book-loving friend — imagine James Wood filtered through the eclectic, all-American, hip omnivorousness of David Foster Wallace — who has impeccable taste but knows that the real classics are books you’ve never heard of.

Yes, the shop’s contents are divided into sections, but they aren’t the ones you’d expect to find in Barnes & Noble: One is titled Anarchy, another Muckraking. One is denominated Stolen Continents. An entire large bookshelf is devoted to banned books (and impishly contains “The Great Gatsby” and “Madame Bovary”). And one set of shelves, reaching from floor to ceiling, contains books put out by the bookshop’s imprint. In an age when publishing is said to be dying, City Lights is busy bringing out short stories by Ry Cooder; fiction by the undying hero of small presses, Charles Bukowski; and works by such graying revolutionaries as Angela Davis and Noam Chomsky.

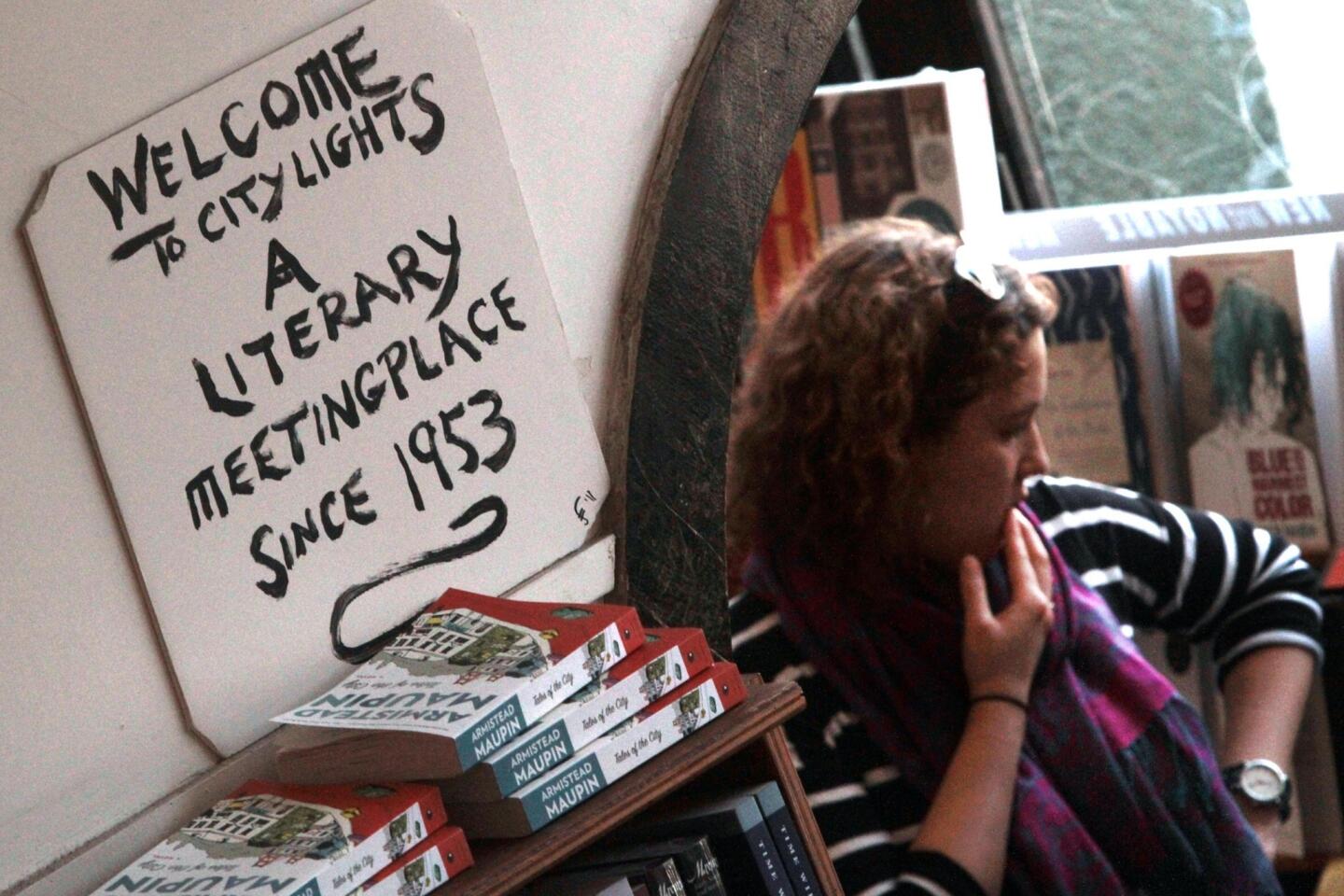

This hunger for revolt is especially impressive in a place that could very easily rest on its laurels. It was at City Lights, after all, that Allen Ginsberg, Kerouac and Kenneth Rexroth found ways of making their voices heard. There’s a Beat Museum now across Broadway from the bookshop, complete with the 1949 Hudson featured in the recent film of “On the Road,” driven into the store by the film’s main actor. But City Lights is the real Beat Museum, because it at once embodies the spirit that turned America on its head in the 1950s and invigoratingly carries it into a new generation. At the Beat Museum, you pay $8 to enter an inner sanctum of manuscripts and artifacts; at City Lights, you can breathe the air of revolution for free.

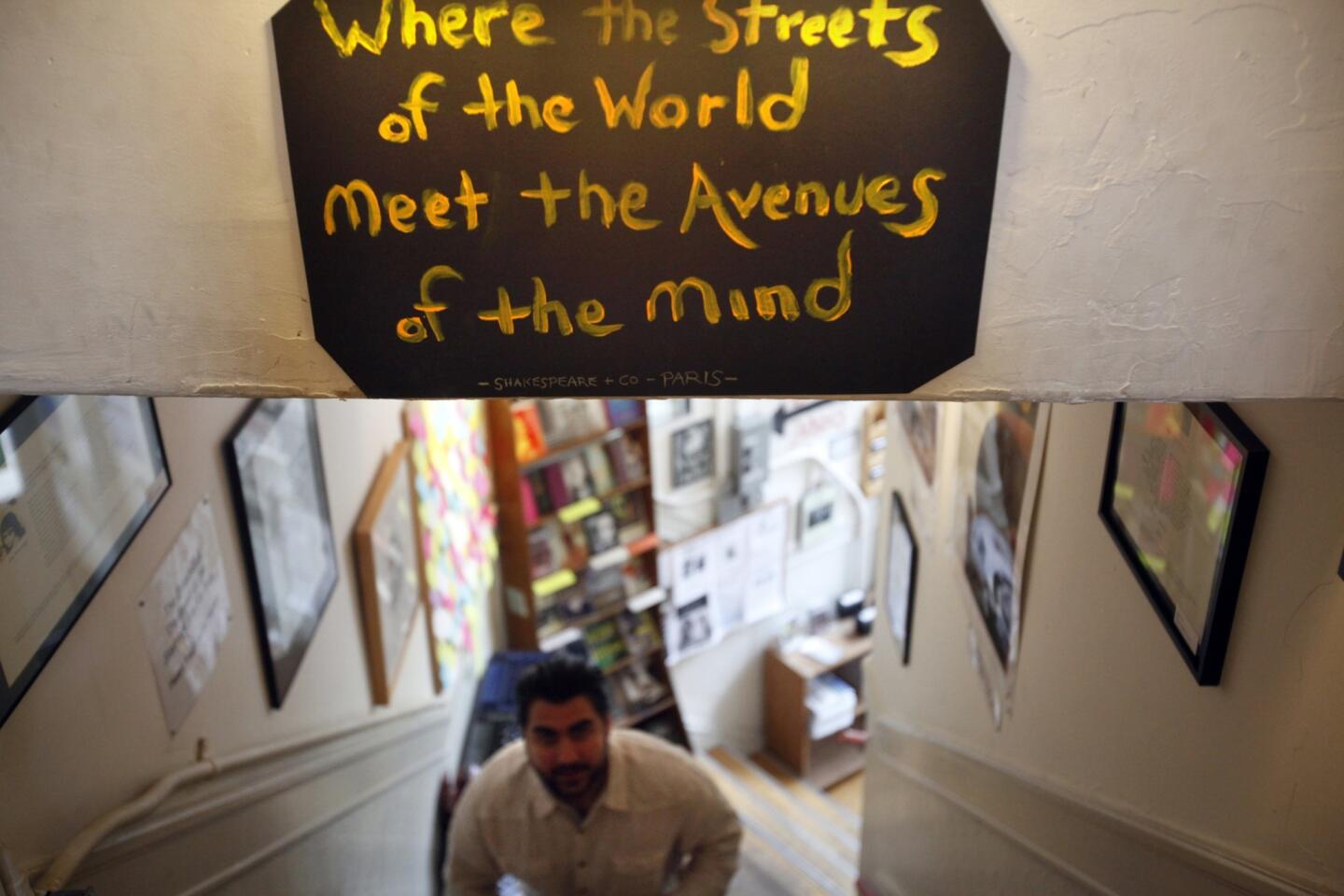

Not many years ago, such bastions of independent spiritedness and uncertain profits could be found everywhere, from Hatchard’s on Piccadilly in London to Shakespeare & Co. across from Notre Dame in Paris. But in recent times, though those two survive, some of the hoariest sanctuaries of good taste and writerly sympathies, such as the Gotham Book Mart in New York and the Village Voice in Paris, have fallen victim to the irresistible pull of e-books and online retailers.

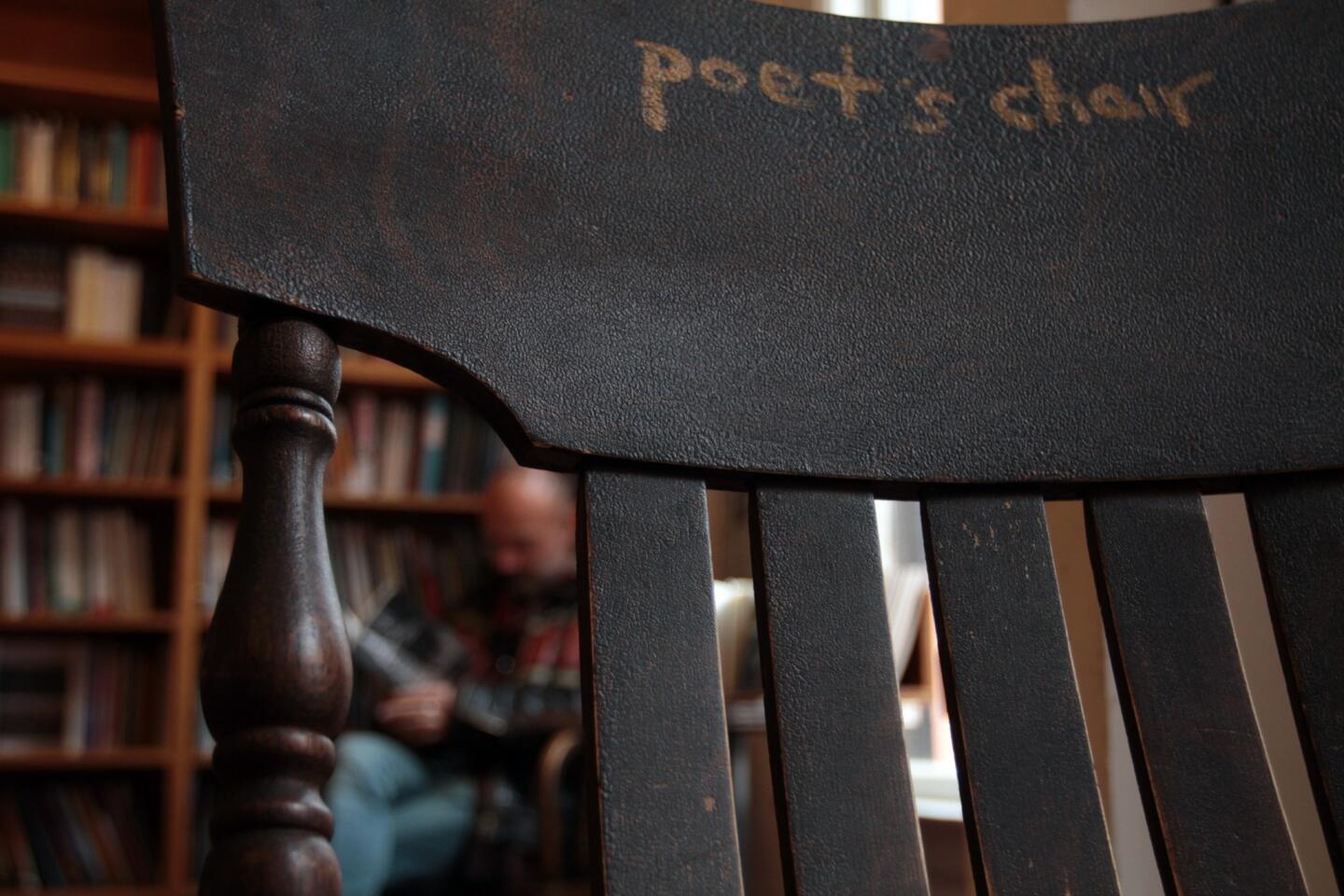

In truth, even megastores have not been able to withstand such forces. The small miracle of City Lights is that it seems to survive — even to thrive — without stocking “Fifty Shades of Grey” and Dan Brown; its second floor is given over to that most unsellable form of literature — poetry — and to get to it you have to walk through a room devoted to fiction, much of it difficult and European, and then a room given over to works from Asia and Latin America.

There are many ways in which you could define the Bay Area: through its ubiquitous high-tech start-ups or its cathedrals to California cooking (Chez Panisse in Berkeley, for starters) or through its abundance of natural beauty and its sushi bars (one, not far from City Lights, advertises raw fish “Like Mom Used to Make”). Irreverence, independent-mindedness and a hunger for far-off cultures have defined it ever since people began streaming into the area in 1849 in search of new fortunes from gold, and a settlement of 812 souls became within two years a city of almost 25,000, many from China, Korea and Australia, clustered around more than 1,000 gambling houses.

Nowadays, the independent bookstore might be an emblem of this. Just off Valencia Street, some blocks away, is a bookshop that offers an hour of Zen meditation before it opens on Saturdays; across the bay in Corte Madera is constantly exploding Book Passage, a mini-empire that runs trips to Italy and writing classes and has almost an entire building devoted to travel. New bookshops are appearing as quickly around the Bay Area as they’re closing everywhere else.

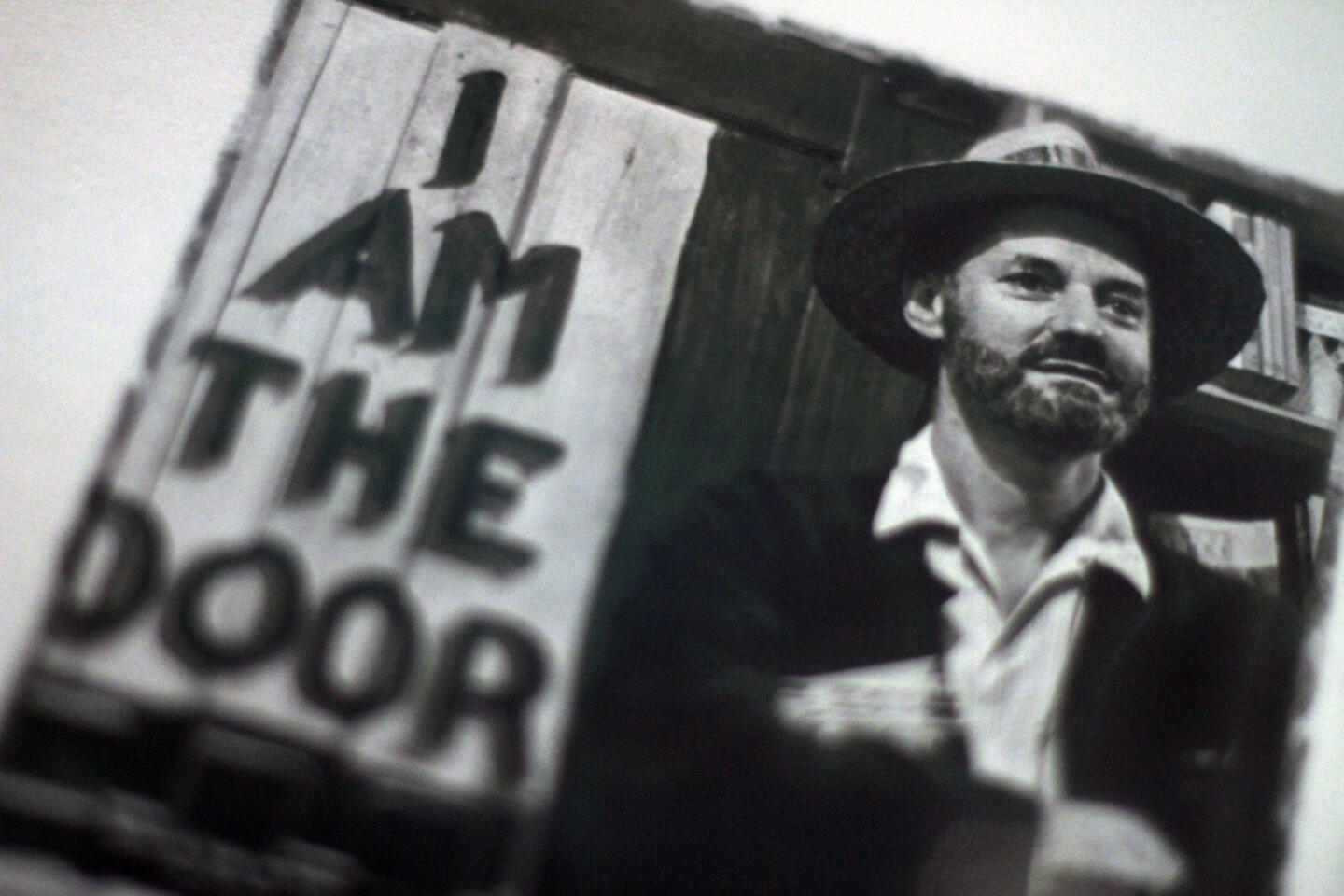

But City Lights is the grand old daddy of eternal youth. Its founder, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, confessed some years ago to still writing poems. Now he’ll be celebrating his 95th birthday on Monday, having seen a hundred revolutions (the Beats, the hippies, the struggle for gay rights, the environmental movement and now techno-gizmos 1.0 and 2.0) come and go, each changing the world a little. When I wrote him a fan letter in my teens — I used to delight in reading his poems from the chapel lectern in our 15th century English classroom — he took the time to write back to tell me that if I wanted to meet poets, I could drop by his shop any time.

Nowadays, a large sign in the shop announces, “Democracy Is Not a Spectator Sport.” One section downstairs, in the dense section devoted to the arts (and sociology and travel), is called green politics. I happened to be looking for an obscure memoir by a film critic in New York, and when I mentioned it to a passing figure, he disappeared into an office and spent many minutes trying to track it down. As he did, I lost myself in shelves devoted to urban theory and Mexican history and cultural criticism, though I couldn’t for the life of me find the section that is often loudest and largest in many a 21st century bookshop: autobiographies.

There are certain beloved writers — including Alexander McCall Smith and Jhumpa Lahiri — that I’d expect to find in any independent bookshop. But City Lights is not like any bookshop I know. I couldn’t count on finding these kinds of authors there, but I could expect to find books I’d never see outside a university library or a secondhand bookshop in Hay-on-Wye, Wales. After 60 years, it somehow remains radical, ahead of the curve and fresher — more clearly in love with the word — than any other bookshop I know.

As I walked back onto the street, after hours of immersion in what felt like a teeming, nondigital mind, I looked again at the woman at the cash register, who was unapologetically dismissing customers in search of memoirs. The lipsticked, shaven-headed, fey figure dealing out snark turned out to be a man. Or at least someone in transition.

Shocks, transformations, even workers who take you aback more than once in a single evening are what makes City Lights as great a sight, as well as a call to new thinking, as the constantly shifting metropolis around it. San Francisco can be hard to take in all at once; its epicenter and symbol — City Lights — can be the perfect way to imbibe the local spirit in a single evening. At the entrance to the fiction room, some wise soul has scribbled, perfectly, “Abandon All Despair, Ye Who Enter Here.”

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.