Latinx Files: What is happening in Nicaragua?

- Share via

For the last month, police in Nicaragua have been rounding up and jailing opponents and critics of President Daniel Ortega. These arrests come ahead of the country’s presidential election in November. Ortega is seeking reelection for the fourth time after his party successfully changed Nicaragua’s constitution in 2014 to remove term limits.

At least 20 people have been detained, including politicians running for president, activists and journalists. As Times reporter Julia Barajas points out, the Ortega government is using a law passed last year that makes any act that would undermine Nicaragua’s “independence, sovereignty and self-determination.”

For the record:

10:47 a.m. July 1, 2021An earlier version of this post referred to Chicago Tribune reporter as Lauren Rodríguez Presa. She is Laura Rodríguez Presa.

The crackdown has caused concern and resulted in action from the international community. Allies Argentina and Mexico recalled their ambassadors to Nicaragua last week, and the United States has imposed sanctions on four members of Ortega’s administration.

The Latinx experience chronicled

Get the Latinx Files newsletter for stories that capture the multitudes within our communities.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

“We continue to call on President Ortega and the Nicaraguan government to immediately release presidential contenders Cristiana Chamorro, Arturo Cruz, Félix Maradiaga, Juan Sebastián Chamorro and Miguel Mora and other journalists, civil society and opposition leaders arrested in the current wave of repression,” said U.S. Department of State spokesman Ned Price.

“We condemn this ongoing campaign of terror in the most unequivocal terms, and consider President Ortega, Vice President Murillo, and those complicit in these actions responsible for their safety and for their well-being.”

This is an ongoing development, and we’ll bring you more updates in the coming weeks.

Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

Meet our Latinx staff: Austin Martinez

The Los Angeles Times employs more than 100 Latinx journalists. One of the goals of this newsletter is for you to meet them all. This week I’ve asked Austin Martinez (she/her), audience engagement intern at the Metro desk and a rising senior studying journalism and Latinx media at the University of Texas at Austin, to write a little something about herself.

I’m probably one of the nerdiest people you’ll meet. I used to read the dictionary in grade school, and now I keep an updated list of my favorite words in English on my phone. Sitting alone with my thoughts during the pandemic helped me discover why I’m such a word hoarder.

I’m a 20-year-old Mexican American woman born in Miami and raised in San Antonio — two places with massive Spanish-speaking populations. Yet, my familiarity with the language extends to greetings and cuss words. When my grandparents attended Texas schools during the 1950s, they were ridiculed and punished for speaking the language they learned at home. In some cases, students across the state participated in symbolic funerals, where teachers instructed them to bury their language and whipped them with paddles when they hesitated. Because of these traumatic experiences, many Spanish-speaking people refused to pass on the language to their children — hoping they would navigate the world more safely and freely. They just wanted us to fit in.

Obsessing over English is my way of taking control of the language I was left with, and mourning the one stolen from my family. My non-Spanish tongue shows the successful assimilation into U.S. society my grandparents prayed for. It may have worked. My mom was our family’s first college graduate. She became an educator who teaches English to young students. Meanwhile, I became a top high school graduate and now attend a top university studying words for a living. I may not be the best with the Spanish language, but I assume power over the English language and use it as a tool to change the world as a writer and communicator.

Not understanding a language so deeply rooted in my Mexican culture still hurts. This pain marks the road my family and I are forced to travel in reclaiming our language. But, a language will never define me. If you need to hear from me, listen to my heart. After all, our hearts beat the same pattern despite the sound of our tongues. And as a proud Latina, my words will remain loud.

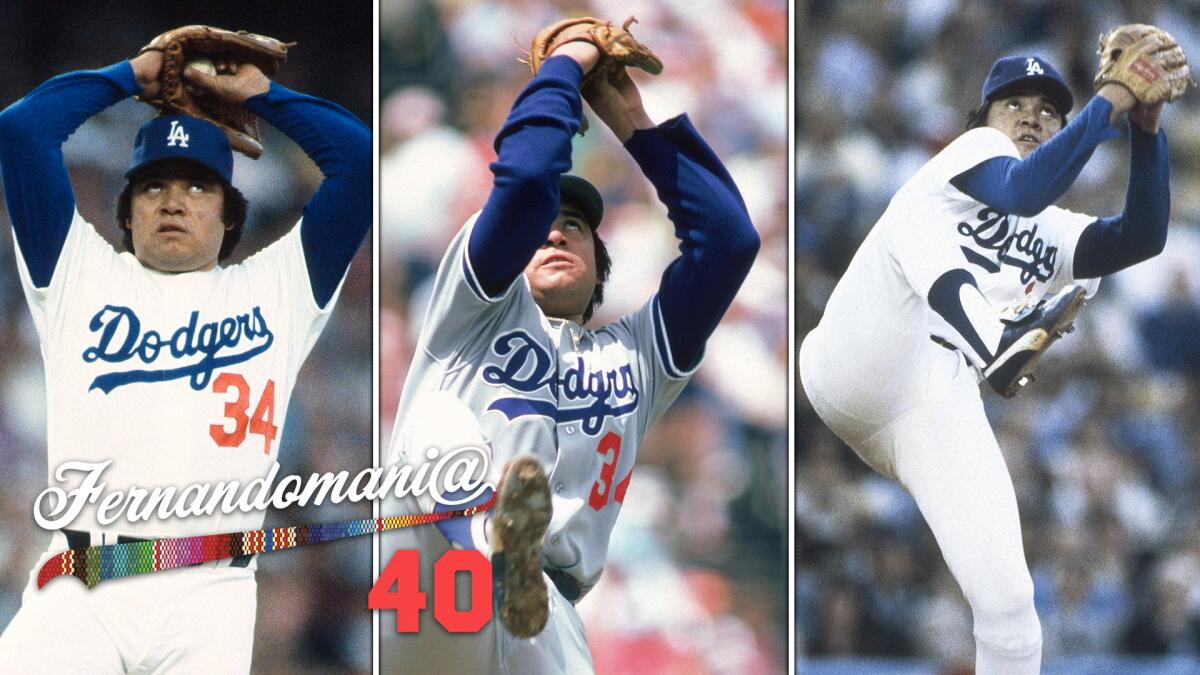

Fernandomania @ 40: What made Fernando Valenzuela so unhittable

The latest installment of our multi-part documentary series “Fernandomania @ 40” is out today. You can watch here.

Unlike previous ones that dealt more with the history and demographic context of what led to the rise of Fernandomania, this week’s episode is a little bit on the insider baseball side of things. It focuses on Fernando Valenzuela’s screwball, the pitch that made him so unhittable.

Only a handful of pitchers in major league history have thrown the screwball with regularity. Even fewer have mastered the pitch. But after the Dodgers’ Bobby Castillo taught Valenzuela how to throw the screwball in the winter of 1979, he went from a minor league prospect to a big leaguer in less than a year. Valenzuela would confound batters with the pitch throughout his 17-year career in the big leagues.

Missed an episode? You can catch up by heading to our special “Fernandomania @ 40” section.

Things we read this week we think you should read

— In the early hours of Thursday morning, a 12-story condo building unexpectedly collapsed in Surfside, Fla.. As of this writing, 18 people have been confirmed dead with 145 more still reported missing. National reporter Jenny Jarvie wrote about the people still missing, who came from diverse backgrounds and different countries. Tragically, Latin America is well-represented. It’s too early to tell what caused the collapse. The Miami Herald has been doing a phenomenal job at reporting this ever-developing story. You can find their entire unpaywalled coverage here.

— Prior to the pandemic, Los Angeles had three people who could professionally restore marimbas, the national instrument of Guatemala. COVID-19 killed two of them. Metro reporter Brittny Mejia spoke to the third, 66-year-old Rosauro Esteban Chonay, who was recently hired to restore a marimba at the Guatemalan Consulate.

— On Sunday, Boyle Heights hosted Orgullo Fest, the neighborhood’s first ever pride festival. The event took place on a stretch of 1st Street that was fittingly anchored on each side by Redz — a bar that has been a queer haven in the neighborhood for more than 50 years — and Noa Noa Place — a newly opened drag bar named after a famous Juan Gabriel song. As my colleague Alejandra Reyes-Velarde reports, the impetus for the festival was born out of a desire to create a bigger space for the L.A.’s Latinx LGBTQ, who are often relegated to a small stage at other festivals across the city despite the fact that Los Angeles County is nearly half Latinx.

“Bienvenidos a casa. You no longer have to leave your community to celebrate yourself,” said Luis Octavio, co-founder of Noa Noa Place and Orgullo Fest organizer.

— For LAist, Frank Rojas spoke with Ayan Vasquez Lopez, member of Mariachi Arcoiris de Los Angeles (an openly LGBTQ group) and creator of the Instagram account the Makeup Mariachi.

— Back in 2015, a group of food vendors in Chicago banded together to rent a commercial kitchen after the city lifted a ban on food carts. In March 2020 that collective, which named the space la Cocina Compartida de Trabajadores Cooperativistas, bought the building. From the Chicago Tribune written by Lauren Rodríguez Presa.

— In the latest Essential Arts newsletter, columnist Carolina Miranda highlights the work of Mexican artist Roberto Gil de Montes, whose paintings channel pandemic isolation.

— You know who loves country music? Latinxs. For The Times, Amanda Marie Martinez wrote about the one-sided relationship between an ever-increasing audience and a genre where “just 0.5% of songs that charted on the Hot Country Songs between 1944 and 2016 were recorded by Latino artists.” One such song happens to be one of my favorites of all time, “Wasted Days and Wasted Nights,” by Freddy Fender, the pride of San Benito, Texas. Here’s Fender performing this banger at a 1979 country musical festival in Rotterdam.

— Danny Trejo has a new memoir coming out. Judging by the profile written by my colleague Daniel Hernandez, it promises to be a page turner. Trejo, a former convict who made a celestial promise to help his fellow man if he got sober, became an unlikely Hollywood star and successful restaurateur. The man clearly has plenty of stories to tell. Of note in Hernandez’s profile is this bomb the actor dropped about Edward James Olmos: “I’m going to tell you the truth. I don’t think Eddie Olmos has accepted me as an actor yet.”

—The Pacific Northwest has been experiencing a severe heat wave. Dozens of deaths have been linked to the record-breaking temperatures. As a result, the United Farm Workers union is asking Washington governor Jay Inslee to issue emergency heat standards to protect the predominantly Latinx agricultural workers trying to save the state’s cherry crops.

— Elizabeth “Betita” Martínez died on Tuesday at 95. She was a prolific author, a pioneering Chicanx scholar and influential organizer. From staff writer Priscella Vega’s obituary of Martínez:

She became the founding editor of El Grito del Norte, a pioneering community newspaper that documented the struggles of Hispanos and Mexicans reclaiming land grants from the U.S. government. She taught women how to write stories, encouraged travel to educational conferences and instilled unity among them. Their work gained national recognition from luminaries such as [activist Olga] Talamante.

The Latinx experience chronicled

Get the Latinx Files newsletter for stories that capture the multitudes within our communities.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.