‘Your actions are jeopardizing public health!’: Last call in New Orleans as police disperse crowds

- Share via

NEW ORLEANS — Over the past 180 years, the family that runs Antoine’s, a bastion of the French Quarter, managed to keep the restaurant open despite the Civil War, two World Wars, Prohibition, the Great Depression and Hurricane Katrina — but not the coronavirus.

This week, with three deaths and 136 coronavirus cases statewide, most in the New Orleans area, Louisiana’s governor closed bars and restricted restaurants to takeout orders until April 13 to prevent the disease’s spread. Antoine’s shut indefinitely.

“Who’s going to come and get a pompano Pontchartrain takeout?” owner Lisa Blount said as she sipped her last wine Monday night. “I can’t give you Antoine’s on Grub Hub.”

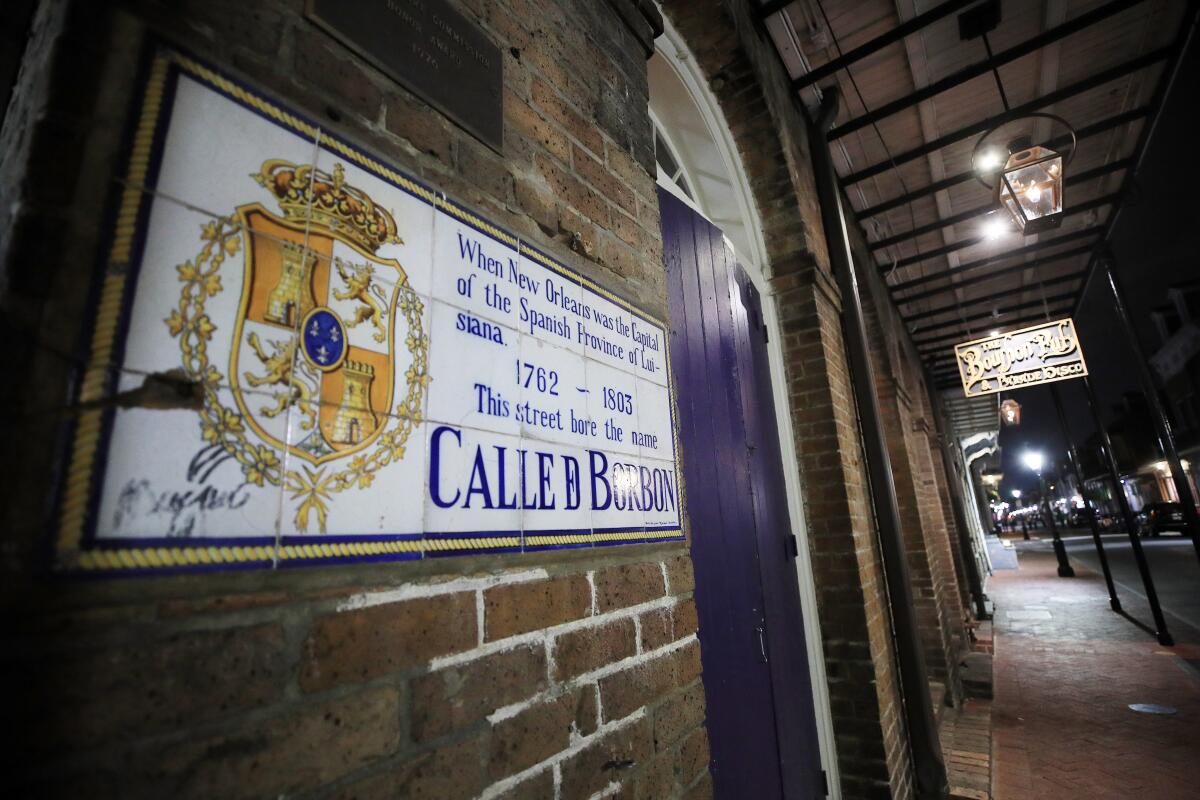

Few U.S. cities are as dependent on fine dining and drinking to drive tourism and the local economy as is New Orleans. The coronavirus arrived during peak spring tourist season, forcing the postponement of a slew of events including the French Quarter Festival and leaving the fate of others like Jazz Fest in doubt. And this week’s sudden closures are likely a preview of what’s to come for other cities, imperiling culinary institutions and leaving hundreds of the chefs, bartenders, waiters and kitchen staff they rely on adrift.

Blount and her husband had to temporarily lay off most of their 165 staff members, including entire families who have served up oysters Rockefeller and crevettes rémoulade for decades.

None of them was prepared for the restaurant to close so quickly, including the Blounts.

“I still had good things on the books, mega parties for St. Patrick’s Day,” Lisa Blount said wistfully. “And this weekend, that started to fall apart.”

Late Sunday, Mayor LaToya Cantrell limited restaurant and bar hours and cut capacity in half.

Waiters at Café du Monde kept tables empty to create social distance between powdered beignets and steaming cups of café au lait. Lucky Dog hot dog vendors placed hand sanitizer and Lysol atop their carts. The Natchez riverboat set sail as usual from the French Quarter with loads of tourists. Cruise ships continued to dock nearby, dropping off scores of travelers.

There was only so much staff could do at Pat O’Brien’s bar, home to the hurricane cocktail since the 1940s, as crowds filled their courtyard and nearby Bourbon Street. By nightfall, police had descended, dispersing crowds, drawing ire and spawning videos viewed by millions.

“Large groups of people are prohibited from congregating!” officers can be heard shouting in the videos. “Your actions are jeopardizing public health and we are directing you to clear the streets!”

On Monday, smaller crowds returned to the French Quarter. So did police, although they remained on the periphery until after dark, when they started going door to door, enforcing restaurant and bar closures.

“How do we keep going and keep the experience of Antoine’s?” Lisa Blount wondered aloud, surrounded by empty tables and walls covered with Mardi Gras regalia from generations past.

Restaurants have been blindsided by the coronavirus pandemic. Here is a guide to services available to those affected, including financial and legal aid.

Chris Shaw, an attorney and self-described foodie from Albuquerque, had driven to New Orleans with his wife to celebrate his 60th birthday this week after canceling a trip to Morocco due to coronavirus travel restrictions.

They had reservations to dine at Commander’s Palace in the city’s Garden District, drawn by its history of noted chefs.

“You can’t do takeout at Commander’s Palace — you have to wear a suit jacket. That’s where Emeril Lagasse got his start,” Shaw said as he finished his coffee at Café du Monde on Monday.

They had planned to see Charmaine Neville — Aaron Neville’s niece — sing at Snug Harbor Jazz Bistro on Frenchmen Street this week. But that, too, was canceled. They tried Tipitina’s jazz club — also closed.

“We went to a stall in the French Market and asked if they would be open and she said, ‘They’re closing down the whole city,’” said his wife, Susannah Abbey, 51. “The number of Louisiana people who have it has just exploded.”

Dr. Geoffrey Konye was visiting from Los Angeles with several friends to celebrate his 40th birthday on Bourbon Street.

“When we left California, everything was OK in New Orleans,” said Konye, who works at an emergency room at Garfield Medical Center in Monterey Park.

The group were resigned to the disease’s spread and said closing bars and restaurants wouldn’t make much of a difference.

“Either way, we’re going to face it,” Konye said.

One of his friends, a nurse from Sacramento, had been exposed to a potential coronavirus patient, got tested and was still awaiting the results.

Nearby, waiters and dishwashers stood smoking and chatting in the streets, unable to believe they could be out of a job even as tourists searched for places to eat.

“This is a party city,” said Shawn Shorts, one of seven dishwashers at the Gumbo Shop who were laid off Monday.

Shorts, 44, had just started work last week for $10 an hour, meaning he won’t be eligible for unemployment benefits.

Kenneth Sexton, a hotel worker and dishwasher at Felix’s Oyster Bar off Bourbon Street, said his friend’s uncle was among those who died from the coronavirus in Louisiana, so he understands the threat. But he also worried about how service workers were supposed to protect themselves without jobs.

“It’s destroying the economy,” said Sexton, 35. “It’s stopping us from making the money to provide for our families.”

The state edict forced the owners of Pat O’Brien’s to place more than 300 employees on unpaid leave, some of whom had worked at the bar for 50 years.

“We knew we wouldn’t be spared,” manager Spencer Theard said. “What can we do? Safety comes first.”

As the bar’s courtyard filled before last call Monday, Theard was optimistic.

“We’ve been through 9/11,” he said. “We’ve been through Katrina. People always come back.”

But an eerie quiet enveloped Bourbon Street shortly before midnight as bars emptied and police cars rolled past.

A handful of locals gathered with their dogs outside Toulouse Dive Bar, one of the few to stay open until the bitter end. Regulars were welcome, including street performers from Jackson Square who showed up dressed as zombies. Those seeking tourist drinks like hurricanes and hand grenades were turned away.

As last call approached, neighbors huddled on the bar’s doorstep and debated the unthinkable over plastic cups of red wine and tap beer: Would the highways close like they did during Hurricane Katrina? Was now the time to hunker down, or leave? Could the government impose martial law?

“We’re just all kind of hanging on day to day,” said Sarah Stelly, 39, who works at a nearby shoe store.

They knew how to navigate a hurricane, but not this.

“Last call!” shouted the bartender.

By midnight, Bourbon Street had closed.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.