Thousands of miles from their Mexico home, coronavirus took their lives — and the economic lifelines of their families

- Share via

AHUEHUETITLA, Mexico — The glazed urn rests in a makeshift altar in the family home, flanked by flowers, candles, Roman Catholic images and a faded snapshot of a middle-aged man.

“We always thought that my father would return home one day,” said Mayra Tlatelpa Baez. “But not in ashes.”

Her father, Benito Medardo Tlatelpa Calixto, was 55. He died April 13 in New Jersey, one of at least 2,045 Mexican citizens lost to COVID-19 in the United States.

In recent weeks, authorities have begun repatriating their ashes. The urns, packed into cardboard boxes, are arriving in hometowns and villages throughout Mexico.

COVID-19 deaths in the United States cut an especially wide swath of bereavement here in the central state of Puebla, where impoverished agricultural towns like Ahuehuetitla have long sent their sons and daughters to work in the New York City area — where the pandemic claimed its greatest U.S. toll.

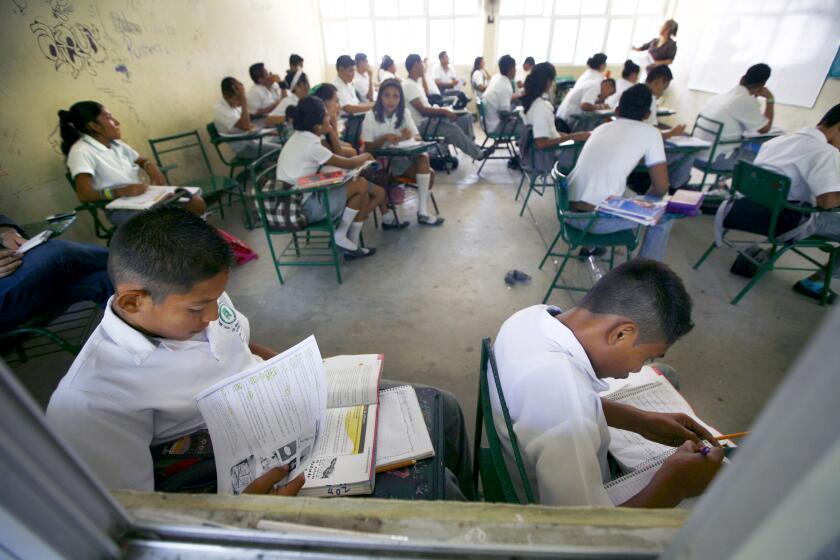

With schools closed indefinitely because of the coronavirus, Mexico’s 30 million students will receive their education over network television.

Behind the ashes are doleful stories of family separation and vanished dreams of immigrants who hoped to retire in their homeland. Many of the victims had not seen their loved ones in years but kept in touch by phone and video and regularly sent home money, mostly from low-wage jobs in restaurants, shops, factories, hospitals and construction sites.

The process of returning their ashes was delayed for months as families and Mexican diplomats navigated COVID-19 restrictions. Fear of contagion ruled out repatriation of bodies for traditional wakes, funerals and burial in Mexico. Instead, relatives agreed to cremations in the United States, forgoing the time-honored rituals of closure.

Last month, New York Archbishop Timothy M. Dolan presided at a blessing of the cremated remains of 250 Mexican citizens — including those of Tlatelpa Calixto — at St. Patrick’s Cathedral, iconic shrine to a previous generation of immigrants.

“Thanks to these 250 heroes … this city kept on functioning,” Jorge Islas López, the Mexican consul general in New York, said at the service. “They were invisible and anonymous heroes.”

After the ceremony, the ashes were loaded on a Mexican military jet and flown to Mexico City. From there, state and local authorities delivered the urns to homes or nearby towns for pickup.

More than a third of the Mexican COVID-19 victims in the U.S. resided in the New York area, and the majority of those came from Puebla. Many were in the U.S. illegally, largely ruling out regular visits to relatives in Mexico.

Tlatelpa Calixto entered the United States more than 20 years ago. His wife, Isabel Baez Vaquero, and the couple’s two small boys followed three years later, leaving their two daughters with relatives in Ahuehuetitla.

Baez Vaquero stayed in the U.S. for 12 years before returning here to be with her daughters. Her husband and sons remained in New Jersey.

Tlatelpa Calixto worked a variety of jobs — at a plastics factory and at packinghouses for fish and vegetables — though near-blindness from diabetes had recently left him unemployed.

As the years passed, the prospect of a family reunion faded. Hanging on a bedroom wall of the family home in Mexico is a cherished portrait: father, mother and all four grown children posed in the sunlight at a graduation ceremony.

But the scene is only fantasy, a composite created on a computer.

Perhaps no place in Mexico was as ravaged by U.S. coronavirus deaths as Ahuehuetitla, in the parched Mixteca highlands.

Carved from volcanic rock at the entrance is a sculpture of a campesino in a broad-brimmed Mexican sombrero, with the head of a jaguar glaring from the pedestal — a testament to the town’s agrarian character and its Indigenous roots. The official population is 1,800, but 90% live in the United States.

At least 26 natives have died of COVID-19 in the U.S., according to Eboly Morán Bravo, the town’s síndico, or legal representative.

“This is something that hit us very, very hard — we are all in mourning,” said Morán. “It’s a personal tragedy, and an economic blow.”

In a one-story house along an unpaved road, Ausencia Guadalupe López, 73, was grieving for her daughter.

María Irasema Vaquero López, who was 43, had moved to the U.S. when she was 16. A single mother of seven, she cleaned apartments in Brooklyn, a job she continued to do even as the pandemic raged.

One day this spring, she called her mother to say she had caught a bad cold after going to work without her jacket. A week later she was hospitalized, diagnosed with COVID-19 and put on a respirator.

On April 16, her mother was roused from sleep by a niece who had just received a call from the United States.

“Brace yourself,” she said. “María is gone.”

A widow who had watched all four of her children leave Puebla for the U.S., López remained especially close to María.

“She would call me all the time, sometimes three or four times a day,” recalled López, who herself spent three years in Brooklyn, working in a clothing factory. “And she would always send me some money, even if it was just a little that she could afford.”

María’s ashes were returned last month after the ceremony at St. Patrick’s. Her children — all U.S. citizens — had wanted to accompany the ashes to console their grandmother, but an uncle talked them out of it.

“I told my nephews that it was too dangerous to travel,” recalled Nereo Vaquero, speaking by telephone from Brooklyn. “Why put themselves at risk? Or risk bringing the virus to my mother?”

For Mayra Tlatelpa Baez, 31, her father’s death thousands of miles away has raised deep doubts about the region’s time-honored tradition of emigration. The custom has brought a measure of prosperity to a town where small plots provide little more than subsistence. But it has also left an ineffable legacy of loss and abandonment.

The last time she saw him was 15 years ago — nearly half her life.

“I have come to believe that it would have been better if our father had stayed with us ... even if all we had to eat was a tortilla with salt and beans,” she said. “We could have worked together in the fields. I could have embraced him.”

At least 23 other families in Ahuehuetitla are still waiting for pandemic ashes to be repatriated from the United States.

Special correspondents Cecilia Sánchez and Liliana Nieto del Río contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.