A sorrowful U.S. death toll of 500,000 from COVID-19: ‘Not just another number’

- Share via

WASHINGTON — COVID-19 deaths in the United States surpassed 500,000 on Monday, the latest desolate way station in a vast landscape of loss.

The toll is hard to fathom. It’s as if all the people in a city the size of Atlanta or Sacramento simply vanished. The number is greater than the combined U.S. battlefield deaths in both world wars and Vietnam. Last month, based on average 24-hour fatality counts, it was as if the terror attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, had happened every single day.

“You see that number, and it’s not just another number,” said Bettina Gonzales, 39, whose 61-year-old father, David Gonzales, a popular football and basketball coach in Harlingen, Texas, died in August. “It’s a lot of tragedy that goes behind that number.”

Recorded COVID-19 deaths in the U.S. account for about one-fifth of the world’s nearly 2.5 million known fatalities from the disease, twice as many as in Brazil, the next-hardest-hit country. California alone accounts for almost 50,000 deaths, about 10% of the country’s total. Nearly 20,000 of those were in Los Angeles County, where about one in every 500 people has died.

President Biden, marking the sorrowful milestone Monday evening, urged the nation to honor the dead by observing public health measures to help bring an end to the pandemic.

“The people we lost were extraordinary. They spanned generations. Born in America, immigrated to America. But just like that, so many of them took their last breath alone in America,” he said in remarks at the White House. “We have to resist becoming numb to the sorrow. We have to resist viewing each life as a statistic.”

Biden and Vice President Kamala Harris, along with their spouses, then stood in silence amid 500 candles — to commemorate 500,000 dead — placed along the steps of the South Portico. The Marine band performed “Amazing Grace.”

Poets and philosophers — and social-science researchers — know that enormous numbers of deaths can become abstractions. For America as a whole, that may be so; for those touched by individual grief, it’s the opposite.

People who have lost loved ones or have suffered lasting physical harm from an episode of COVID-19 sometimes speak of feeling stranded on the far side of a great chasm, alienated from compatriots who wonder when they will be able to go back to bars and baseball games.

Among millions of mourners, some can still scarcely believe that a loved one who had survived so much else was swept away.

Ralph Hakman, a Holocaust survivor, was vigorous into his 90s. But in the pandemic’s early days, he suddenly fell ill and died March 22, twelve days after his 95th birthday.

“If not for COVID, I really believe he would have lived past 100,” said his 89-year-old widow, Barbara Zerulik, who was sickened around the same time as Hakman and diagnosed with COVID-19. Her husband was not tested for the virus, but doctors believe it killed him.

Born in Poland to an Orthodox Jewish family, Hakman survived three years in Auschwitz before immigrating to the U.S. He raised two children in Beverly Hills with his first wife, also a Holocaust survivor.

“He survived such brutal hatred and violence when he was young — he was so strong,” said Zerulik, who spent months in the hospital and rehabilitative care before moving to Jacksonville, Fla., to live with her daughter. “Then this disease brought him down.”

Public figures reached into history to find parallels for these soul-trying times. Biden’s chief medical advisor, Dr. Anthony Fauci, said Sunday in a television interview that half a million deaths is like nothing “we have ever been through in the last 102 years, since the 1918 influenza pandemic.” U.S. deaths then were a cataclysmic 675,000, though dwarfed by a worldwide toll of 50 million.

Health officials reported 1,465 new coronavirus cases and 93 related deaths on Sunday, with the lower numbers suggesting the fall/winter surge is abating.

Over the past year, the pandemic has left few American lives unscathed. All the ways in which society organizes itself — school and work, economy and governance, friendship and family life, love and romance — have changed, in some instances irrevocably.

Ohio kindergarten teacher Holly Maxwell used to love giving hugs to her little pupils when they were in need of comfort. Her school outside Uniontown has been holding in-person classes all year, but she has only a dozen students instead of the usual 22, and six feet of social distance are carefully observed.

That means no cluster of 5-year-olds around Maxwell’s rocking chair for story time, no playing together with building blocks and puzzles.

“The social-emotional effects of this are going to be huge for this age group,” said Maxwell, a 48-year-old mother of two who has taught for 22 years. “They’re supposed to be learning how to be friends — they want to play together. It hurts my heart.”

The contagion has wrenchingly altered end-of-life farewells and rituals of mourning. As David Gonzales, the Texas coach, lay dying after a month on a ventilator, nurses called his daughter, Bettina, from his hospital room on FaceTime. In the confusion, the phone in his room was turned to the wall, and Bettina’s screen went blank.

“I could hear the chest compressions, air rushing through his body,” she recalled. “Ultimately, I heard the flatline.”

Caring for the dead — so many, many dead — has been both an extraordinary burden and a sacred duty. That duty lies close to home for Michael Fowler, the 62-year-old coroner for Dougherty County in rural southwest Georgia.

In his close-knit, majority Black community, he has tended to the bodies of neighbors and relatives, zipping up the body bag over a familiar face.

“When so many of the dead are your friends and co-workers, it takes a toll,” he said.

Since March, he has pronounced 267 COVID-related deaths, answering calls in the middle of the night, taking photos, notifying kin. Sometimes families were so ravaged by the disease that there was no one to give instructions about which funeral home to use.

“It was just overwhelming,” he said. “A husband would be in the hospital on a ventilator after his wife died.”

During the deadliest month — April, which saw 86 COVID-19 deaths in the county — the local morgue ran out of room, and the Federal Emergency Management Agency brought in refrigerated 18-wheelers to store bodies.

Fowler has lost so much weight that he has to pin up his trousers. He hasn’t had a vacation in months. He often goes to the office at night to fill out paperwork, missing out on sleep. But his latest duty has given him a glimmer of hope: notifying county residents where they can get vaccinated.

“I can see the light now,” he said. “With the vaccine, and all the precautions everyone’s taking, things are going to get a whole lot better.”

This is not the pandemic’s darkest hour; that may have already passed. New U.S. cases have been falling for five weeks; the vaccine rollout, despite lags and shortages, is trending toward success — although it is also a race against deadly new variants that are circulating in the U.S. and around the world.

The pandemic has laid bare shocking U.S. social disparities that were present all along but thrown into stark relief by the crisis.

Black people and Latinos are much more likely to suffer devastating medical outcomes. Economic inequities abound, with wealthier work-from-home Americans weathering the outbreak with comparative ease, even while unemployment has soared to levels not seen in decades, leaving millions of American families unable to pay for necessities such as housing and food.

At the same time, there was a bleak commonality to the threat: COVID-19 has ravaged crowded urban neighborhoods as well as lonely prairie towns, leapfrogging inexorably from coast to coast.

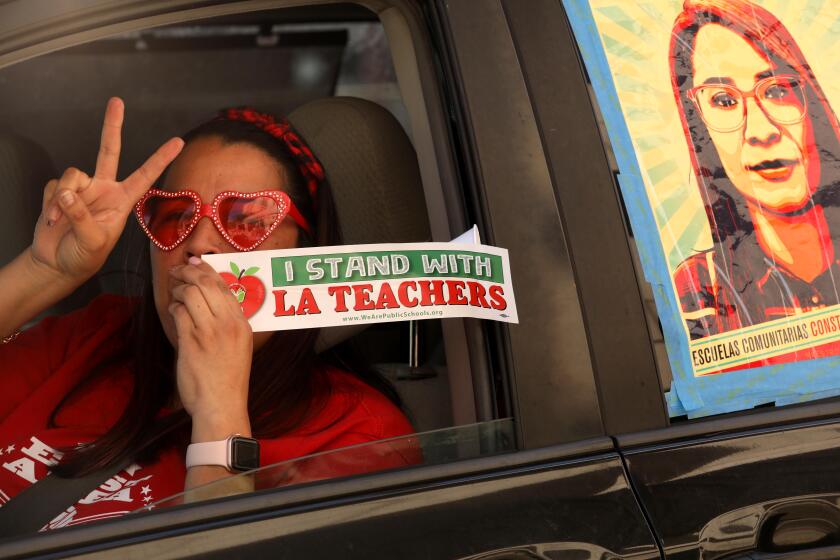

Gov. Gavin Newsom sought to hasten schools’ reopening with his vaccine allocation plan, but the L.A. teachers union remains opposed to reopening until community infection rates drop further and vaccines take full effect.

For healthcare workers across America, the disease has been a merciless, months-long onslaught, threatening their own physical and mental health as they have struggled to care for others.

“There is hope, but at the same time, such grief for all that we’ve lost and all that we’re still going to lose,” said Shira Doron, an infectious-disease physician and the hospital epidemiologist at Tufts Medical Center in Boston. “We cannot lose sight of the hundreds of thousands of people gone.”

The pandemic has been a source of singular anguish even for those accustomed to dealing daily with sickness and death.

“The sadness, the devastation, is something all of us in medicine have never seen,” said Michael White, a 46-year-old hospital physician in Phoenix, a virus hot spot in an especially hard-hit state.

But White said sheer human resilience had sometimes amazed him. He saw family patriarchs fight their way back to health, COVID-stricken pregnant women recover and deliver their babies safely, a long-hospitalized father keep a vow to go home to his kids.

“It gives us hope to keep on providing,” he said, “and battling this virus.”

As the disease continued its relentless march, the elderly were hit the hardest, with those over 65 accounting for about four in five U.S. deaths, and many nursing homes and assisted-living facilities ravaged. But contagion clawed its way into all age categories, sweeping away some of the young and healthy, afflicting children with a still poorly understood inflammatory syndrome.

Medical experts say the pandemic has indirectly claimed many thousands of lives, with ailments undiagnosed and treatments deferred.

From the earliest months of the outbreak, projections by infectious disease specialists were, by definition, imperfect, because they were dependent on public behavior and policy choices. But over the months, the pandemic’s terrifying progression spoke for itself.

It took four months for the benchmark of 100,000 deaths to be reached, in May 2020. But by Jan. 19, when the toll reached 400,000, it took only five weeks for that number to grow to 500,000.

What everyone wants to know, of course, is when it will end.

At 52, Navajo Nation Police Officer Carolyn Tallsalt has two decades on the job, but she said this past year had been her hardest yet.

The Navajo Nation, spanning portions of Arizona, New Mexico and Utah, has recorded nearly 30,000 coronavirus cases and more than 1,100 deaths. Tallsalt, who patrols in Tuba City, Ariz., 220 miles north of Phoenix, said she was disheartened when she saw people gathering inside homes and breaking the nightly curfew because they believed the threat had largely passed.

“They think, ‘Oh, things are better — there is a vaccine,’” she said. “It’s misguided thinking.”

Tallsalt hopes the awful marker of 500,000 deaths will be a reminder for all Americans to safeguard their health as best they can.

“Let’s hope there isn’t another 100,000 deaths,” she said. “I don’t want to see 600,000.”

Staff writers King reported from Washington, Lee from Phoenix and Kaleem from Los Angeles. Staff writers Molly Hennessy-Fiske in Brownsville, Texas; Richard Read in Scottsdale, Ariz.; Jenny Jarvie in Atlanta; Emily Baumgaertner in Los Angeles and Eli Stokols in Washington contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.