Patels are a success story from India to the U.S. Why do they want affirmative action?

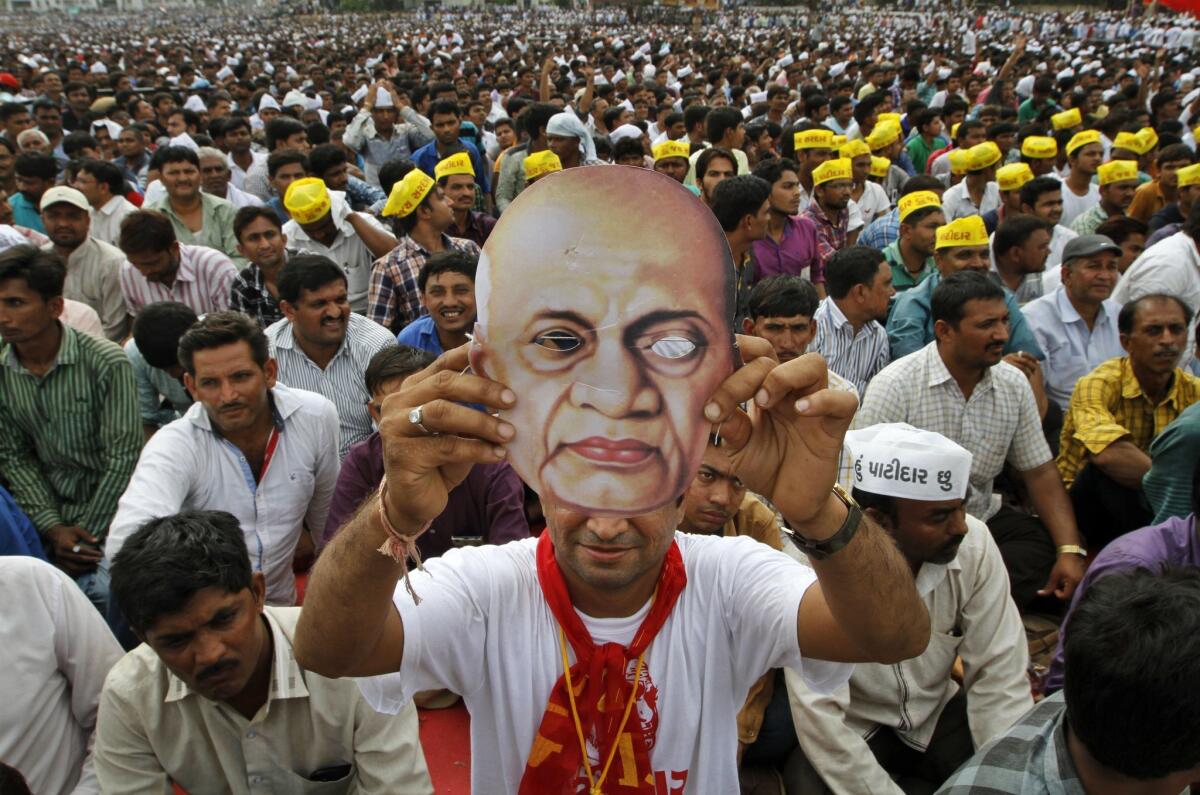

A Patidar, or member of Patel community, holds a mask of Indian freedom fighter and first Home Minister of Independent India Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel as he participates in a rally in Ahmadabad, India, Tuesday, Aug. 25, 2015.

- Share via

Reporting from Mumbai, India — They are one of India’s most prosperous communities, a name synonymous with commerce as far away as the United States, home to at least 145,000 of them.

Now Patels in the Indian state of Gujarat want the government to give them a new label: “backward.”

Huge crowds are expected to gather Tuesday in Gujarat’s capital, Ahmedabad, to demand that quotas for school admissions and government jobs be extended to the Patel community. They argue that India’s byzantine, decades-old affirmative action system known as reservations — designed to elevate historically marginalized castes and tribes — has left them behind.

“Either the government grants us reservation or discontinues the entire concept of reservation,” the leader of the movement, a young businessman named Hardik Patel, told a crowd last week. “There is no other option.”

Patels make up 15% to 20% of the 63-million people in Gujarat, a vast coastal state and centuries-old trading hub. Traditionally farmers, they have gained huge shares of the state’s diamond and textile industries, and hundreds of thousands have emigrated to the United States and Britain, where they are regarded as among the most economically successful immigrant groups.

Many find it puzzling that Patels would be agitating for the same benefits that India’s 1950 constitution enshrined for forest-dwelling tribes and those once known as “untouchables,” the lowliest community under the hierarchical caste system.

NEWSLETTER: Get the day’s top headlines from Times Editor Davan Maharaj >>

The government later extended the quotas to other marginalized groups it collectively dubbed “other backward classes” — a category the Patels now want to be a part of.

“It’s laughable,” said Aakar Patel, a commentator and head of Amnesty International’s India office.

“It’s like Jews saying they are economically weak and don’t have access to modernity. The Patels are just as powerful and united a grouping. They have had access to modernity and capital for a century and a half. Almost every person in central Gujarat, where Patels dominate, has family members in the U.S. and UK.”

Yet the rallies have drawn thousands across Gujarat in recent weeks, hinting at simmering discontent in a state that its former leader, Narendra Modi, now India’s prime minister, has long touted as an economic model.

Patels have been among the staunchest supporters of Modi and his Bharatiya Janata Party, which controls both the central and state governments. Gujarat’s current leader is a Patel, as are seven of her Cabinet ministers and 40 of the BJP’s 120 state lawmakers.

Analysts say Gujarat’s manufacturing-heavy economy has suffered as the diamond and textile industries lose ground to foreign countries and India relies more heavily on services. Under the BJP, Gujarat de-emphasized teaching English in government-run schools, which some say has harmed young job-seekers in an increasingly globalized India.

“The so-called Gujarat model has not been able to generate employment for the younger generation,” said Achyut Yagnik, a prominent sociologist. “Patels have invested in small and medium enterprises, which have declined in Gujarat.... So the younger generation thinks their future is not bright and reservations are the only way out for them, because they see others benefiting from it.”

The reservation system has promoted employment and encouraged higher education rates among India’s most disadvantaged communities such as Dalits, formerly known as “untouchables,” who traditionally were confined to cleaning sewers and other objectionable jobs.

But it has also generated resentment from excluded groups that has periodically flared into communal violence, as in the 1980s, when Patels launched anti-reservation protests in Gujarat.

At rallies, Hardik Patel has said that he does not want to take away existing quotas but complained that Patels with high test scores are denied medical school admissions and other coveted educational slots that go to low-scoring members of the “scheduled” communities.

India’s Supreme Court has ruled that reservations in any state cannot exceed 50% of slots, a threshold that Gujarat has already reached. The state’s chief minister, Anandiben Patel, has said “we cannot make any changes” in the quota system, although her government was meeting with Patel community members in an effort to lower temperatures.

Members of other marginalized communities have pledged to “uproot” the state government if it accedes to the Patels’ demands.

On the eve of Tuesday’s planned demonstrations, which police said would draw hundreds of thousands to the city, residents in Ahmedabad said officers were out in large numbers and many businesses were planning to remain closed.

“There is some kind of restlessness at the ground level,” said Ghanshyam Shah, a retired professor. “The government is really panicked.”

Special correspondent Parth M.N. contributed to this report.

For more news from India, follow @SBengali on Twitter

ALSO:

Islamic State evokes more shock with reported destruction of ancient temple

Americans, Briton who subdued gunman on train receive France’s highest honor

Why the fate of the historic Iran agreement could remain uncertain for years

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.