Great Read: India test cheating stirs outrage — then people start dying

- Share via

Reporting from Indore, India — The police officer casts a cursory glance at the first-time visitors and, with an efficiency unusual for India, waves them down a concrete corridor toward the office of the man he’s supposed to be guarding.

Anand Rai is the only doctor working for the health department here in the central state of Madhya Pradesh who gets a bodyguard. But he’s also the only one who’s gotten death threats for blowing the whistle on a school-cheating scandal with a growing body count.

Rai has repeatedly asked for tighter security. The khaki-clad officer at the entrance arrives at 11 a.m. and leaves at 7 p.m. He has Sundays off. And he works for the same state government whose top officials are implicated in the scam that Rai helped expose.

SIGN UP for the free Great Reads weekly newsletter

“Everyone tells me to be careful,” said Rai, a telegenic 38-year-old ophthalmologist. “In reality, I am just riding my luck as far as security is concerned.”

Six years after Rai first complained to police that state medical school exams were being leaked, the extent of the cheating scandal in Madhya Pradesh has become outrageously clear. Whistle-blowers say that over nearly a decade, tens of millions of dollars exchanged hands to rig the tests that help determine university slots and civil service jobs, allegedly with the complicity of senior politicians in one of India’s most populous states.

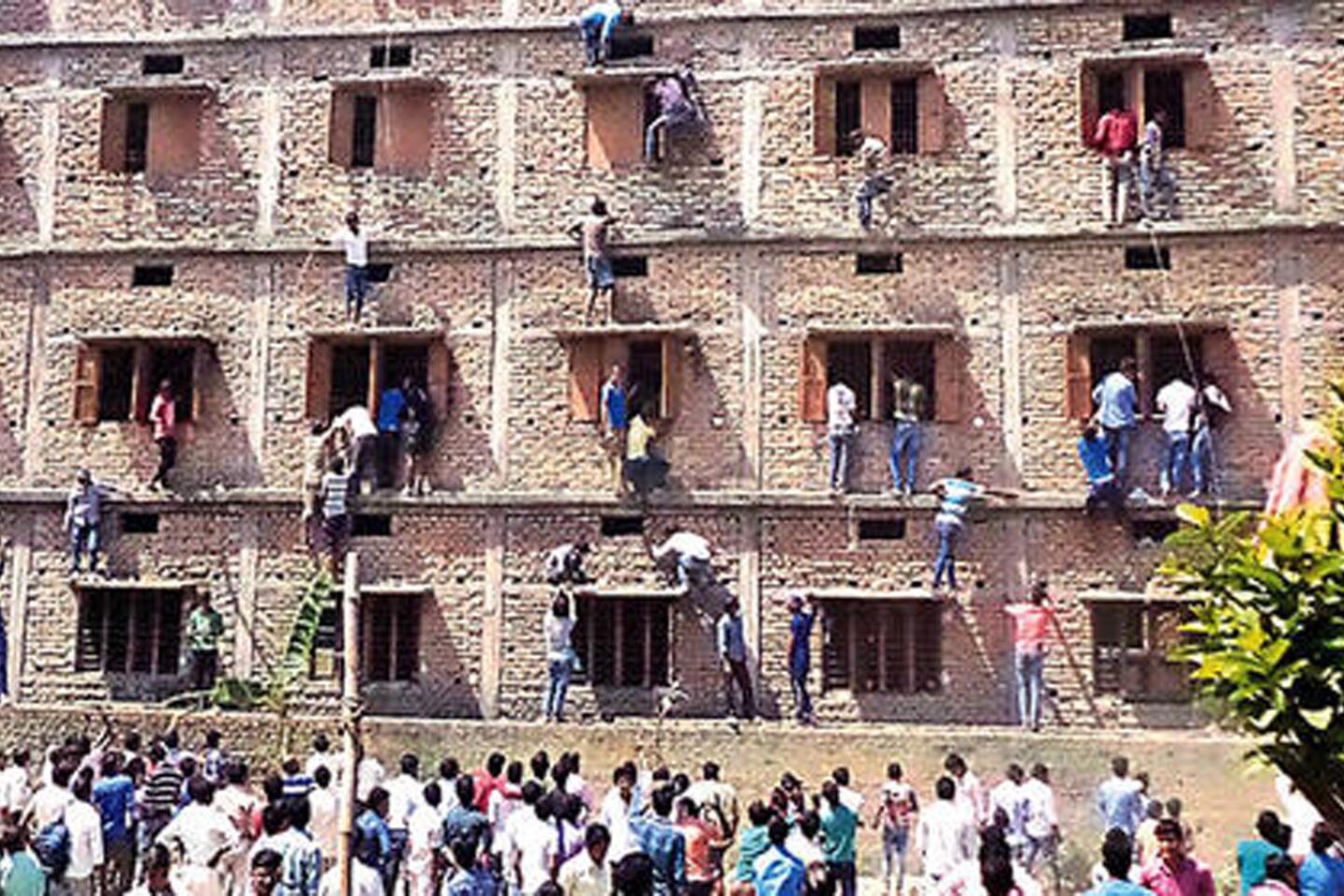

Colluding with the state examination board, known by the Hindi acronym Vyapam, rival test-fixing gangs helped at least 2,000 students con their way into coveted medical colleges and many more land police and other government posts, authorities say.

More than 1,800 people have been arrested — mostly suspected cheaters, middlemen and testing administrators — and hundreds more are on the run.

The scandal, colossal even by India’s notorious standards for graft, has grown more explosive in recent weeks with the sudden deaths of several people reportedly connected to the case.

Investigators said last month that 23 people named in the scandal had suffered “unnatural deaths” since 2009, most commonly in road accidents.

Then came a string of more deaths.

A prisoner awaiting trial on charges of helping two students cheat died of an apparent heart attack.

A journalist collapsed after interviewing the family of a student suspected in the scam, herself the victim of an unsolved killing in 2012.

A medical college dean who fed information to investigators was found dead in a hotel room, a year after his predecessor died of burns.

“You can’t look at this number of deaths and say it is routine,” Rai said.

A staffer appeared in his office with glasses of water, and as his visitors sipped, Rai remarked, almost casually, how easy it would be to slip poison into a drink.

“You wouldn’t even know if it was dissolved,” he said.

::

Exams for medical school, the holy grail of higher education in India, are crazily competitive. In Madhya Pradesh, Rai said, 50,000 pre-med applicants compete for about 700 seats, an acceptance rate of 1.4%.

Harvard’s 2014 undergraduate acceptance rate was a comparatively promiscuous 5.9%.

With so much pressure, cheating is an open secret. A 2003 Bollywood hit, “Munna Bhai M.B.B.S.,” told the story of a crime boss who hires a proxy to help him get into a medical college to impress his dad.

Since then, exam-hall stand-ins have a name in India: “Munnabhais.”

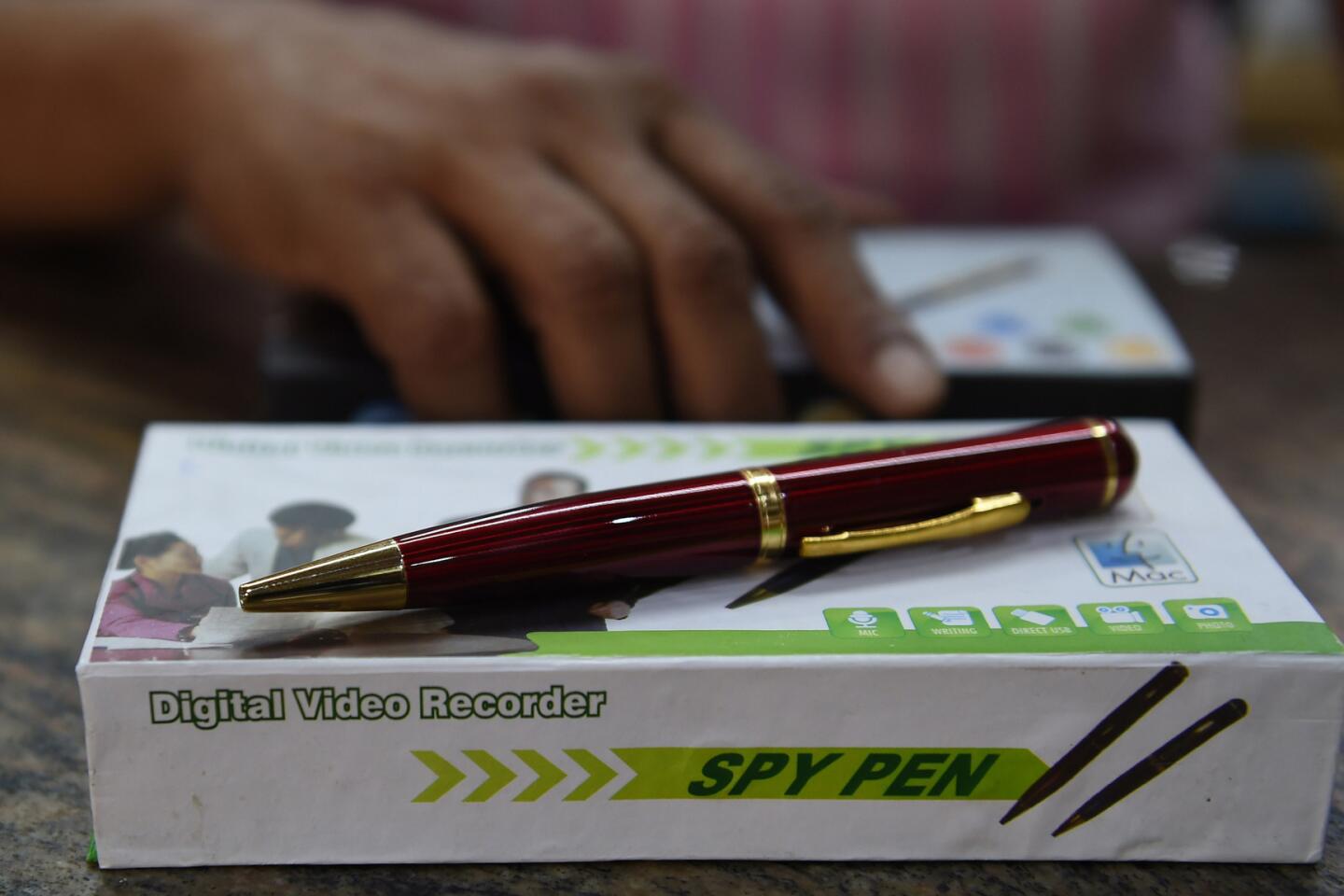

Rai knew from his student days that test copies were routinely leaked, and grew more suspicious after his 2005 doctoral exam when almost everyone from a single dormitory block qualified. In 2009, he told Indore police about a racket that was distributing exam questions and arranging for Munnabhais — usually brilliant older students — to take tests on behalf of paying clients.

On the eve of exams in 2013, Indore police arrested 20 people who said they were promised as much as $1,600 to pose as test-takers and help others in the exam hall cheat. That set off a chain of arrests that included the head of Vyapam, Pankaj Trivedi, and revealed that cheating gangs had mushroomed across Madhya Pradesh.

Like rivals in any industry, Rai said, the gangs competed on price and services, creating a range of options.

Students could pay to see all or part of the test, or have someone take the test for them.

They could have the seating chart in the testing hall manipulated to help them copy answers.

They could even submit a blank answer sheet, secure in the knowledge that it would be filled in with the correct answers later, once the exam controllers had received their cut.

The rates ran to $30,000 and higher for a 12th-grader seeking a place in a medical college, a fortune in Madhya Pradesh, a state with one of the lowest per-capita incomes in India. Gaming the tests for advanced degrees in lucrative disciplines — like Rai’s specialty, ophthalmology — reportedly exceeded $160,000.

“It was a systematic process,” Rai said, “and a big business.”

Whistle-blowers say the scandal’s effect runs far deeper, into the rotten core of a university system and civil service hollowed out by years of fraud.

“Many students changed disciplines. They are lost in life after investing so many years,” Rai said. “Most of them are very bright people, and they are getting disheartened at the age of 23, 24.”

When Poonam Sharma took her first medical school test, she knew she faced long odds because classmates bragged that they had paid thousands of dollars to see the questions beforehand.

For three years she was denied admission despite good scores.

“It was depressing to lose out by such a narrow margin, plus knowing the ones who got in were frauds,” the waif-like Sharma, now 24, recalled. “These students would ask me, ‘Why aren’t you getting your admission done through money?’”

Sharma battled depression as her police officer father dug deeper into the family savings to pay for extra tuition.

She filed court petitions. And in late 2013, after the first arrests in the Vyapam case, she and two other students went on an eight-day hunger strike demanding that aspirants on the waiting list, like her, be granted admission. Her weight dwindled to 77 pounds.

Last year, after the exam board was dismantled and a nationwide pre-med test was used in its place, Sharma won a place at a medical college in Indore.

Even as the scandal makes headlines, she remains skeptical that those responsible will be punished.

“Police officers, bureaucrats, politicians — all powerful people are involved,” she said. “I am not confident of a fair investigation. Who will catch whom?”

::

In the combustible atmosphere of small-town India — thick with rumor, hysteria and more than a whiff of high-level corruption — the recent deaths set off a frenzy.

Nothing conclusively ties the fatalities to the cheating scam. But Mint, a usually sober financial newspaper, declared in a front-page editorial that “a murderous rampage is on.” India’s Supreme Court termed the events “shocking” and last week ordered the Central Bureau of Investigation, India’s FBI, to take over the investigation from state authorities.

The scam allegedly ran all the way to Madhya Pradesh’s governor, Ramnaresh Yadav, who tried to secure forest guard posts for five people. One of the deaths being examined by federal investigators is that of Yadav’s son, also accused in the case, who died in March, reportedly of a brain hemorrhage.

Last month, Narendra Tomar, an inmate accused of arranging impostors to take the pre-med exam for two students, complained of stomach pains after dinner at the district jail in Indore and died a few hours later from what doctors said was a heart attack.

The news stunned his relatives, who had spoken to him by phone the night before and said the 30-year-old had no history of medical problems.

“It is not a natural death,” said his younger brother, Munnu.

The family’s misgivings remain just that. But they are egged on by politicians in the opposition Indian National Congress who allege a conspiracy to silence witnesses.

Sanjay Pandey, the jail’s superintendent, said a judicial inquiry had found no evidence of foul play in Tomar’s death, and that inmates accused in the scandal are “as safe here as they would be anywhere else.”

But the next day, Pandey’s department asked a judge to transfer the 17 Vyapam suspects to another facility, saying the Indore jail “does not have elaborate medical facilities” to deal with emergencies.

Perhaps Rai, now a fixture on Indian news networks, has become too high-profile to be harmed. But he worries about his wife, a gynecologist in the state health service who is posted an hour’s drive from Indore, and their 2-year-old son.

“They want me to run away from the state and they are doing everything they can to put pressure on me,” Rai said. “I am not going to run away.”

Special correspondent Parth M.N. contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.