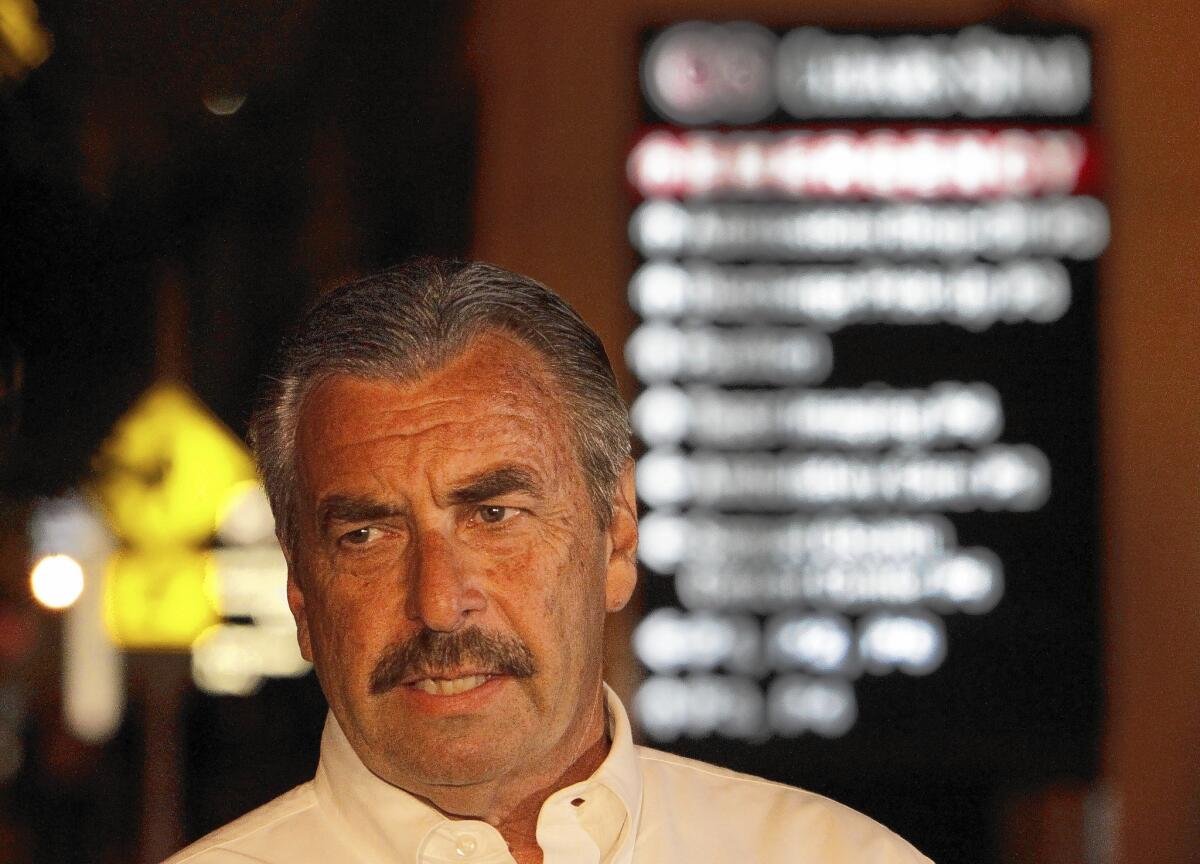

LAPD Chief Charlie Beck regains footing after troubles in spring

- Share via

Charlie Beck received a blunt message from one of his civilian bosses as he prepared to request a second term as chief of the Los Angeles Police Department: He was no longer a shoo-in for the job.

Police Commissioner Paula Madison demanded a meeting with Beck in April and told him she was concerned about a recent string of controversies and his apparent lack of transparency with the five-member oversight panel he reports to.

“When I stepped into this role, I didn’t expect that we would be looking for a new police chief, but now we may need to consider it,” Madison recalled telling Beck.

Other commissioners shared her concerns. Some were displeased enough with Beck that they alerted Mayor Eric Garcetti, who appoints the commissioners and wields considerable influence on their decision. The mayor, in turn, summoned the chief.

Garcetti asked Beck to explain his plans for the future should he be given a second five-year term. It was “a frank discussion,” according to commission President Steve Soboroff, who was briefed on the meeting.

Beck went to work making amends. He began meeting regularly with each commissioner in private — something he had not done previously — in an effort to build their trust and address their concerns.

In interviews, commissioners said Beck has pulled off a convincing about-face in recent months. Despite some lingering concerns, a majority of the five-person commission — Kathleen Kim, Madison and Soboroff — said they favor giving Beck a second term. A fourth commissioner, Sandra Figueroa-Villa, declined to comment but has been a vocal supporter of Beck.

The fifth commissioner, Robert Saltzman, said he was encouraged by Beck’s recent efforts but remains undecided about his future with the department.

Commissioners said they were withholding final judgment until they completed a series of private meetings with the chief and public hearings, the last of which is Tuesday. The commission has until mid-August to vote on whether to offer Beck another five-year term.

Although Beck has managed to assuage much of the commissioners’ worry, more issues have arisen in recent weeks that could still cause trouble for him.

Most pressing is an audio recording that surfaced last month of a training seminar given by veteran Det. Frank Lyga in which he makes comments that have been widely interpreted as racist and sexist. Saltzman said the commission was awaiting more information about the case but expressed concern that department officials appeared to have taken little action and did not notify the commission, despite knowing about the recording for several months.

“Shoes just keep dropping,” Madison said last week.

Before the recent tension with his bosses, Beck had cruised relatively unscathed through his first term in a period of relative calm for the scandal-prone LAPD. Beck established himself as a capable leader and oversaw continued declines in crime, according to department statistics.

He guided the department through budget cuts that included the near elimination of cash to pay officers for overtime. As many of the department’s roughly 10,000 officers accumulated hundreds of hours of unpaid overtime, Beck oversaw a plan that forced large numbers of them to take time off each month in lieu of being paid cash. The strategy strained resources as Beck and his commanders scrambled to make do with a depleted force.

Beck, when he thought it was necessary, did not shy from confrontations with his officers and the union that represents them.

Early in his tenure, he took a hard line with officers in specialized units who refused to disclose information on their personal finances. Beck disbanded the units and rebuilt them with willing officers.

Later, he invited controversy again when he tightened the rules for impounding cars of unlicensed drivers. The change was needed, he said, to help immigrants living in the country illegally who were unfairly affected by the impound rules.

The move won accolades from immigrant advocacy groups but drew the ire of conservative groups and the police union, which is challenging the rules in court.

Beck’s greatest vulnerability is on issues of officer discipline. Commission members clashed with him repeatedly over the years, saying he was inconsistent in how he punished cops and too often gave warnings for serious misconduct.

Decisions Beck made on discipline set off his recent clash with the commission. In February, he opted not to punish a group of officers involved in a flawed shooting, which drew a public challenge from Soboroff. A few weeks later, members of the oversight board, along with many officers, criticized the chief for not firing Shaun Hillmann, a well-connected cop who was caught making racist comments.

Those controversies were followed the next month by revelations that officers in South L.A. had been tampering with recording equipment in patrol cars to avoid being monitored. Commissioners demanded to know why Beck had left them in the dark about the matter and questioned whether the chief was committed to working with his civilian bosses. Madison put Beck further on his heels by raising concerns that he was unprepared to deal with a coming wave of retirements among his top commanders.

For his part, Beck downplayed the rough patch. He chalked up much of it to the fact that, except for Saltzman, commissioners had been on the panel for only a few months when the Hillmann case erupted.

“It was a new relationship,” he said in an interview. “We had some issues that, I think, if we had been in a longer relationship still would have been significant but wouldn’t have been as dramatic.”

Nonetheless, Beck acknowledged that he has had to change. “I have to explain more and make sure that I don’t take things for granted — that people will automatically understand why I do what I do just because I understand it.”

The experience, he added, was a sharp reminder that he needs “to make sure that this commission understands me and the department and sees me as a willing partner with them.”

Madison said she believes Beck’s efforts in recent months have been genuine. She pointed to how he initially was not receptive to her suggestion that he hire an outside consultant to help plan for the upcoming wave of retirements, but he eventually agreed.

And Commissioner Kim, a law professor, said Beck’s outreach has given her the chance to better understand his stance on immigration issues — an area of particular interest to her — as well as discuss her concerns about the string of troubling incidents in the spring.

Looking forward, Beck said he wants a second term because, he said, “I’ve got more to do.”

“I didn’t just wake up after 41/2 years and have a new vision for the Los Angeles Police Department,” he continued. “It’s the same vision, I’m on the same road that I’ve been on, I just need more time to get to the destination. I want a Police Department that is seen as part of the community, not over the community. I want one that is embedded in every fabric of Los Angeles.”

If Beck is given the time he wants, Soboroff said he believes the recent string of controversies will have ultimately helped the chief. “If the chief gets reappointed, he will be a better chief because of it,” Soboroff said. “He’ll be more responsive.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.