‘Robotic’ response triggers police suspicion

- Share via

BERKELEY — The blond girls whom Phillip Garrido introduced as his daughters were pasty white, even though it was the end of summer, and seemed robotic and unusually submissive.

They called Garrido “Daddy.”

Two UC Berkeley police employees who interviewed Garrido and his daughters this week said at a news conference Friday that they knew something was wrong because the girls obviously were not normal.

Police said Garrido fathered the girls with Jaycee Dugard, whom they say he kidnapped 18 years ago when she was 11 and kept in the backyard of his home in Antioch, northeast of Berkeley.

Garrido and the girls showed up Monday on the Berkeley campus, where they distributed fliers and met with Lisa Campbell, manager of special events for the UC Police Department.

Garrido told her he wanted to hold a campus event he called “God’s Desire,” which he frenetically described as having to do with schizophrenia and the FBI.

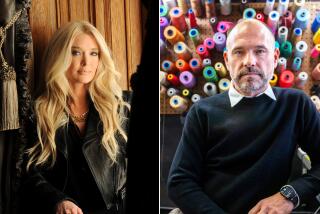

Campbell, 40, a former Chicago police officer, said she found it curious that the girls were not in school and appeared not to have spent any time in the sunlight. Campbell said that Garrido was “clearly unstable” but that the girls were even more striking.

Clothed in drab dresses, with penetrating blue eyes that matched their father’s, they were “non-responsive” and exuded no energy, she said.

Busy with other matters and eager to learn more about this strange trio, Campbell asked Garrido to return the next day to plan the event. She then went to campus police Officer Ally Jacobs, 33, and told her something was not right with the three.

Jacobs ran a computer check and learned that Garrido was a federal parolee and sex offender. She joined Campbell in the Tuesday meeting and tried not to arouse Garrido’s suspicions.

“We really didn’t know what we had,” Jacobs said.

Jacobs and Campbell took turns talking to Garrido while the other tried to draw out the girls. They asked the girls their names but couldn’t hear their replies. The names were “hippie-like,” akin to Jasmine and Buttercup.

The younger girl said she was in fourth grade, and her elder sister said she was in ninth grade.

Asked where they went to school, they answered in unison “like robots,” Jacobs said. “We’re home-schooled.”

Whenever the younger girl spoke, her sister would “shoot her a glance” of warning, Jacobs said.

In the meeting, Garrido said matter-of-factly that he had once been convicted of kidnapping and rape. The girls did not react.

Jacobs asked the younger girl about a bump above one of her eyebrows. “ ‘It’s a birth defect. It’s inoperable. I will have it for the rest of my life, ‘ “ Jacobs said the girl replied as though coached. “She just wouldn’t stop smiling.”

Jacobs, the mother of two young boys, said she tuned into her “mother mode” as she watched the girls.

She described the girls as “ ‘Little House on the Prairie’ meets robots, clones.’ ” The elder girl seemed “bothered” when her younger sister said they had an older sister, 28, at home. “Twenty-nine,” the older girl corrected her.

“ ‘I am so proud of my girls,’ ” Jacobs remembered Garrido saying as he put his arm around the elder girl’s shoulder. “They don’t know any curse words.”

At one point, Campbell made eye contact with the older girl, who “quickly caught herself and went back to looking at the ceiling.” Campbell called the younger girl’s smile a “smirk.”

When Garrido and the girls left, Jacobs called his parole officer and suggested he might want to contact Garrido.

The parole officer, whom she did not identify, called Jacobs back and told her Garrido had no children. Maybe they were grandchildren, she said he suggested.

Police arrested Garrido on Wednesday, after he went to meet with the officer at the parole facility in Concord, near Antioch, with his wife, Dugard and the two girls.

Campbell and Jacobs have been lauded for helping free the trio. Jacobs said she never expected to play such a role. She had previously policed tree-sitters protesting a UC development plan.

“For the life of me,” Jacobs said with a grin, “I thought the tree protest was going to be the biggest thing.”

--

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.