Cause for hope -- and fear -- in Pakistan

- Share via

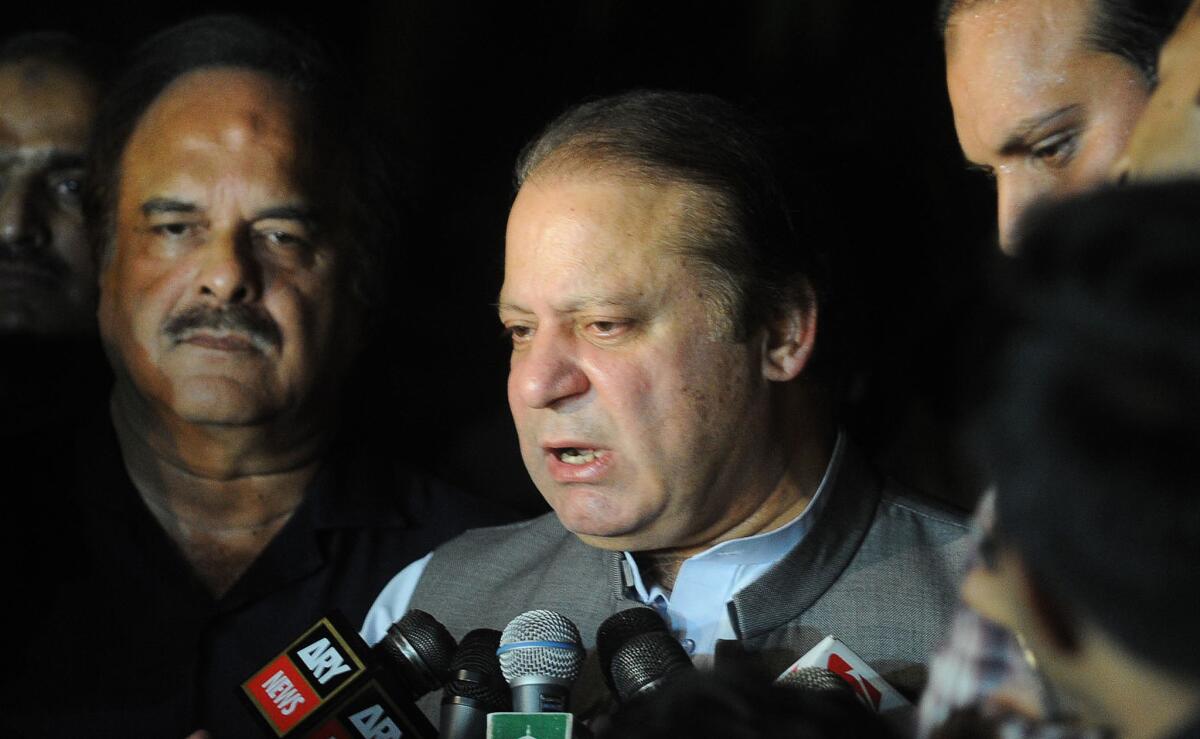

There is reason for hope in Nawaz Sharif’s victory in the recent Pakistani elections. Sharif, who has twice served as Pakistan’s prime minister, has said he wants to build a more robust democracy, revive the country’s shattered economy and end the military’s 40-year domination of its politics. He has also promised to improve relations with India and take on the radical Islamist terrorism that has tormented Pakistan. The United States should assist him in every way possible to achieve those goals.

But there is also ample reason for caution. The U.S. has a long history of “betting on the come,” of unwarranted optimism that the transfer of billions in unconditional aid will influence Pakistan to withdraw its support for the Afghan Taliban insurgency based in Pakistan. With a new Pakistani leader in place, it is time to begin linking Washington’s huge military and economic assistance programs more directly to U.S. interests, including anti-terrorism and regional stability.

Perhaps Sharif’s greatest challenge — as he knows all too well — will be ending the Pakistani military’s outsized influence on foreign and defense policy, which is implemented largely through its powerful intelligence agency, Inter-Services Intelligence. In 1999, the last time Sharif served as Pakistan’s prime minister, he attempted to improve Indo-Pakistani relations and replace the head of the army, Gen. Pervez Musharraf. Instead, the army ousted Sharif in a coup, and Musharraf assumed power. Since 2008, Pakistan’s elected leaders have tended to cede key decisions to the military in order to survive.

Moreover, Sharif does not have an unblemished record in his willingness to confront extremists. During his second stint as prime minister in the 1990s, he played an influential role in the rise of the Taliban in Afghanistan, which was seen to be in Pakistan’s interest. Recently, Taliban extremists in Pakistan spared Sharif’s party in their violent pre-election attacks on political rallies and candidates. Against this backdrop, and given Sharif’s stated opposition to U.S. drone strikes, it seems unlikely that the new prime minister will vigorously combat extremism in Pakistan.

This sobering environment makes it incumbent on Washington to conduct its relations with Pakistan patiently, positively, candidly and in a transactional manner, emphasizing both equality and give-and-take. America’s ineffective policy through successive administrations has seemed paralyzed, tolerating Pakistan’s phony insistence that it does not support Mullah Mohammed Omar’s Afghan Taliban insurgency and the notorious Haqqani network operating from Pakistani territory. With the new prime minister comes an opportunity to change that dynamic.

Sharif, for his part, must understand that he will not be able to accomplish any of his goals — including economic prosperity and stability in Pakistan — unless the ISI’s radical Islamist infrastructure in Pakistan is dismantled.

Another part of the U.S.-Pakistan relationship that needs resetting is Washington’s continuing hope, against much evidence to the contrary, that Pakistan will be useful in guiding Afghan peace talks. In fact, any Afghan political process organized by foreigners, including the U.S.-sponsored Qatar initiative that has languished since 2010, is doomed to failure.

Rather than trying to act as the catalyst for talks between the Taliban and Afghan President Hamid Karzai’s government, the U.S. should step back, encourage the Afghans to reach agreement on their own and insist that Pakistan also step back. It would be nothing less than foolish to continue to work with Pakistan to convert the ISI’s Taliban and Haqqani network proxies into genuine peace negotiators instead of what they are: Al Qaeda-linked terrorists bent on violence to achieve their extremist version of an Afghan Islamist state.

Last year, Congress and President Obama officially designated the Haqqani network as a foreign terrorist organization. Congress should now move quickly to add Mullah Omar’s Quetta Shura to the list. The group’s suicide bombers are no different from those of the Haqqani network, having killed hundreds of American and coalition troops in Afghanistan, along with thousands of Afghans. Both operate with Al Qaeda and share the same ideology, and both were created and sustained by the ISI, and have been supported or unofficially tolerated by Pakistani civilian leaders.

Strategically, Washington should support Sharif’s policies to strengthen the Pakistani economy, democratic institutions, civil society, human rights and gender equality. American responses to Pakistani requests, including on an upcoming International Monetary Fund bailout, must be conditioned on the military’s cessation of support for its Afghan terrorist proxies operating from Pakistani soil.

Concurrently, the U.S. and its allies should urge Pakistan to join a multilateral consensus to revive Afghanistan’s classic buffer role in Central Asia between larger powers. The Afghan government, like Austria during the Cold War, would adhere to nonaligned neutrality. Outside powers, Pakistan included, would honor Afghanistan’s territorial integrity and exercise mutual restraint from interfering in Afghanistan. The outcome — opening up Central Asia to a new era of intercontinental commerce through Afghanistan — would benefit both Pakistan and Afghanistan.

Pakistan is an important, populous Muslim nation poised to move forward under the leadership of a new prime minister. Its success or failure will depend largely on whether its leaders have the strength of will to resist military domination of the Pakistani state and confront radical Islamists. The U.S. should do everything in its power to help should Sharif choose to follow this path.

Peter Tomsen was special envoy and ambassador on Afghanistan from 1989 to 1992 and ambassador to Armenia from 1995 to 1998. He is the author of “The Wars of Afghanistan: Messianic Terrorism, Tribal Conflicts, and the Failures of Great Powers.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.