The Senate preserves the filibuster, averts partisan fallout

- Share via

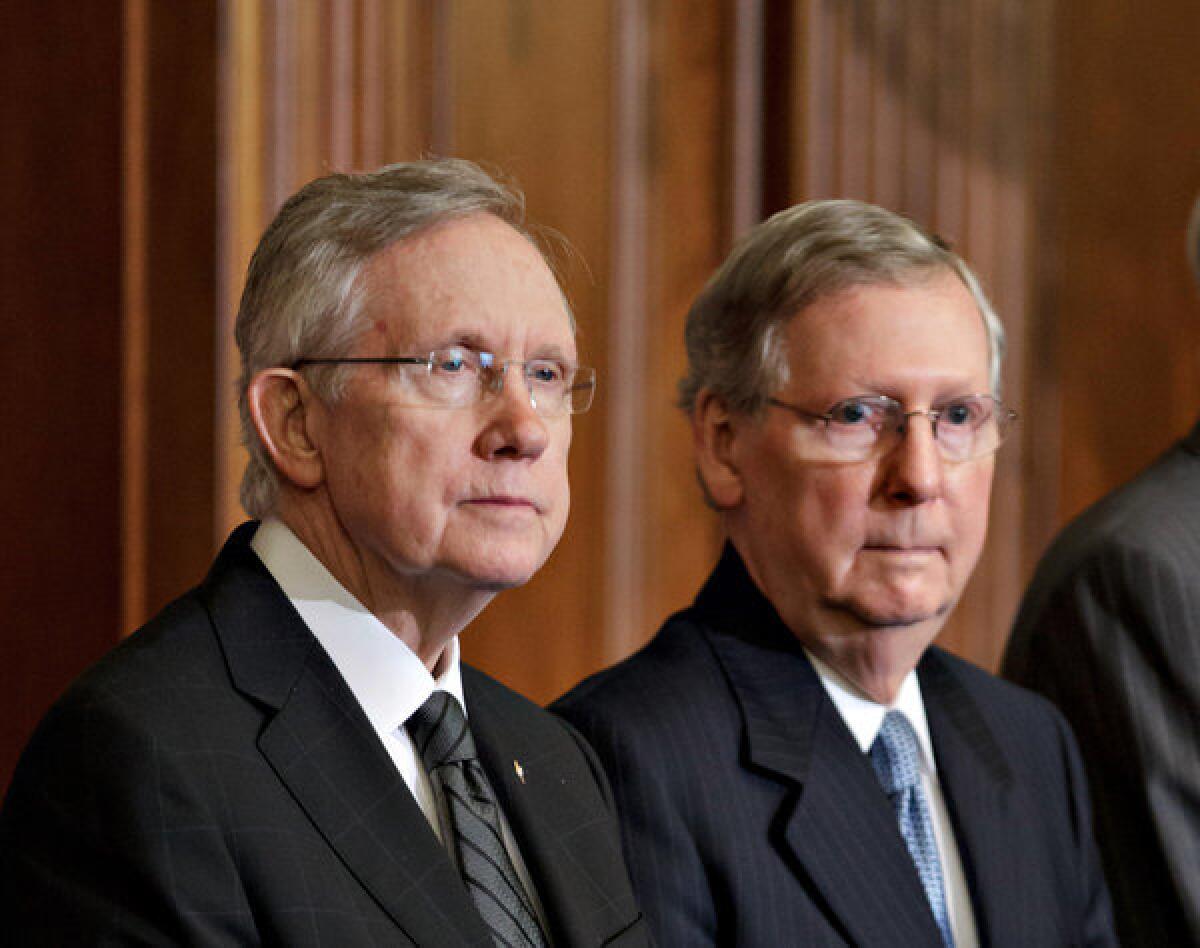

In a now-familiar routine in Washington, lawmakers walked right up to the brink of disaster Monday, only to pull back Tuesday. This time, though, the source of the drama was the Senate, where Majority Leader Harry Reid (D-Nev.) threatened to end the minority’s ability to filibuster presidential nominees for executive branch posts.

Reid relented Tuesday morning after Republicans agreed not to block votes on President Obama’s nominees for secretary of Labor, administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency and director of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. The deal also calls for the Senate to quickly approve two more members of the National Labor Regulation Board after Obama replaces the current nominees with new ones. (More on that later.)

That’s not only the right result, it’s the predictable one. Or at least it should have been predictable. Sharp disagreements lead to difficult negotiations, which means no concessions until the very last minute. The main difference now is that lawmakers seem to be amping up the threats in their search for leverage. Republicans threaten to shut down the government or stiff some of the government’s creditors if they don’t get their way on budget cuts. Democrats threaten to let all temporary tax breaks expire if the GOP won’t agree to raise taxes on the highest incomes.

If you have faith in the legislative process, it’s easy to shrug off the threats. But if you worry that lawmakers put ideology ahead of comity and country, you’re more likely to believe it’s just a matter of time before the worst threats become reality.

Ending the filibuster wouldn’t be as bad as defaulting on the debt, not by a long shot. But it would have so infuriated Republicans, they probably would have used every delaying tactic in the rulebook to stop Senate from accomplishing anything of substance until after the 2014 elections. And as slowly as the Senate moves today, at least it’s still moving.

One reason the GOP would have been so aggrieved is that it would have taken some procedural jujitsu, if not outright rule-bending, to change the filibuster rule by a majority vote instead of the two-thirds normally required to change Senate rules. That’s why the technique has long been called the “nuclear option” -- the collateral damage would have been profound.

And yet it’s hard not to blame the GOP for setting this fight in motion. Although filibusters and other delaying tactics grew increasingly common when Democrats were in the Senate minority in the mid-2000s, they’ve become routine since then. Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) has even sought to hold off votes on noncontroversial issues, such as the confirmation of federal appellate Judge Sri Srinivasan, whose nomination was eventually approved by a vote of 97 to 0.

Worse, the filibuster has been used to stop independent agencies from carrying out their functions by denying them crucial appointees, even when lawmakers generally supported the nominees to fill those posts. In the case of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, lawmakers and stakeholders praised Obama’s nominee for director, Richard Cordray, who’s been leading the agency for more than two years as a recess appointee (after Republicans blocked a vote on his nomination in 2010). But they refused to allow a vote on his nomination unless Democrats agreed to weaken the bureau by replacing the single director with a bipartisan board and letting Congress control its budget.

They relented on this demand, and rightly so. It’s one thing to filibuster a nominee because you think he or she isn’t qualified; it’s quite another to do so because you don’t like a duly enacted law. They also agreed to let Obama restore a Senate-confirmed quorum to the National Labor Relations Board, which has been operating with a majority of recess appointees since January 2012.

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit has ruled the recess appointments of Democrats Richard Griffin and Sharon Block to be invalid, threatening to upend all of the decisions the board has made in the past year and a half. Obama renominated the two earlier this year, but the deal between Republicans and Democrats in the Senate calls for the president to withdraw those nominations and submit new names.

That’s one concession Reid made. The other, larger one is that he evidently extracted no promise from Republicans not to filibuster other Obama appointees. So Tuesday’s disarmament may just be a temporary truce, not an end to the hostilities.

ALSO:

California, catch the next big energy wave

Daum: Rethinking the Cleveland kidnapping narrative

Follow Jon Healey on Twitter @jcahealey

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.