Better ways to grade public schools

- Share via

How do you measure school quality?

For the last decade, the answer has been informed by a single set of data: standardized test scores. Now there is a chance to change that. Although Congress remains unwilling to overhaul No Child Left Behind, with its overemphasis on testing, Secretary of Education Arne Duncan has taken matters into his own hands, issuing waivers that have freed 42 states and eight California districts — including L.A. Unified — from the law’s accountability mechanisms. Waiver recipients are now free to go beyond test scores in measuring school success. But so far, policy leaders seem to be thinking very much inside the box about what to include.

Recently a colleague and I built an online tool for the Boston Globe, designed to evaluate all of the schools in Massachusetts in a more comprehensive way. To do this, we drew on publicly available data. But because our project was not tied to any governmental accountability measures, we were able to think more holistically about school quality, moving beyond raw standardized test scores.

The tool we created is imperfect, and we were severely limited by the data available. Still, we were able to build a better mousetrap. And the project got us thinking: Now that waiver recipients can rethink how to evaluate schools, what would a truly robust measure look like?

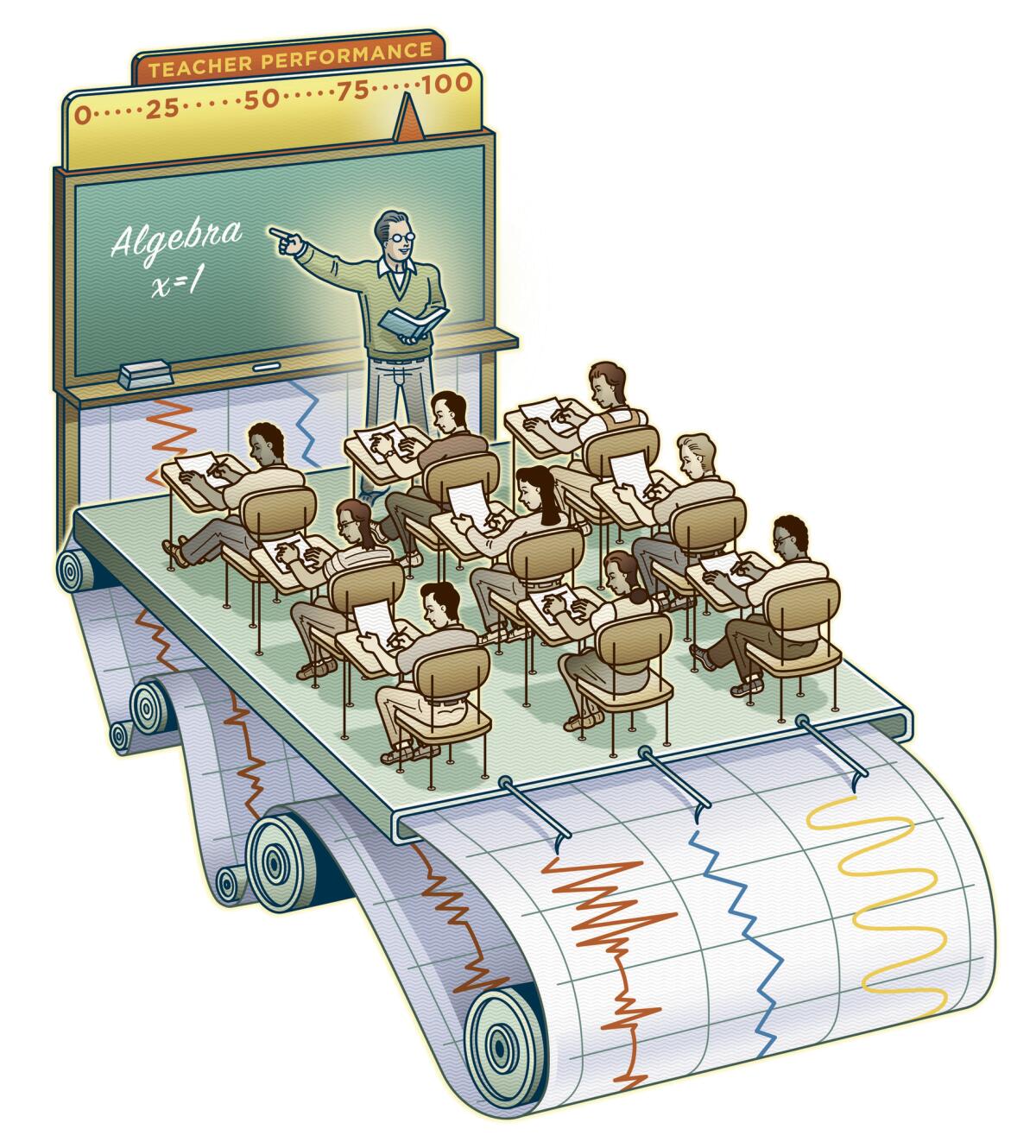

The most obvious gap in available data on K-12 schools is related to teacher quality. Many states and districts have tried to solve this problem by adopting “value added” calculations, which attempt — often unreliably — to measure the role teachers play in raising or lowering student test scores over time. Yet even if such tools are more carefully used, more can be done to measure teacher effectiveness.

We know from research, for instance, that high rates of teacher turnover are problematic. We know, as well, that teachers in their first few years are significantly less effective than those with more experience. Because information on teacher turnover and experience is already collected by many districts and built into school-level report cards, why not incorporate such measures into statewide accountability schemes? And why not also experiment with student evaluations of teachers, or with teacher evaluations of their working conditions? Combined with robust performance-based assessments, such figures would present a much clearer picture of teacher quality.

Policy leaders should also prioritize the collection of data that tell us what it feels like to walk down a school’s hallway. Again, there is some good information already being collected at the school or district level. Los Angeles Unified schools, for instance, have been conducting a “school experience survey” for the last several years. But such measures have played no role in accountability frameworks, largely because of the challenge of collecting the data in a consistent and accurate way.

New technologies, however, such as software applications that can be implemented across multiple platforms, including mobile phones, are making it possible to conduct frequent brief surveys of teachers and students. By posing questions such as “How safe did you feel at school today?” or “How focused were your peers in class?,” we can begin to gain insight into a school’s climate as well as into the social and emotional well-being of students.

Waiver recipients should also lobby for the inclusion of stronger and more direct measures of academic performance. Raw test scores have long been the primary gauge of performance, but they often indicate more about student background — particularly family income — than about the contribution of the school. Advanced data systems, however, have made it possible to compare students at a single school with other students across the state who have similar testing histories and demographic backgrounds.

Thus, by making a straightforward adjustment in measurement, policymakers would not only present a clearer picture of school quality but also end an accountability system that inherently punishes schools serving high-need populations.

Finally, we should consider more systematic collection of data on nonacademic programs in schools. It will require creative thinking to devise appropriate measurement instruments, but Americans generally agree that schools should do more than produce students who can take tests. And we know from research that students engaged in extracurricular activities tend to have more positive school experiences.

So why not report the number of students who receive regular art instruction, the number of students who participate in a school’s music program and the percentage of students involved in clubs or other extracurricular activities? Why not, in other words, hold schools accountable for being schools and not just test-prep paddocks?

Ultimately, of course, there is no perfect measure of school quality. And despite the rhetoric of the accountability movement, any attempt to measure a school is an inherently subjective enterprise. But as long as we are going to rate our schools, we should be working to piece together a picture of them that is multifaceted, rooted in research and congruent with the things we truly value. In short, we should measure what we care about and not merely what is convenient.

Jack Schneider is an assistant professor of education at the College of the Holy Cross and the author of “From the Ivory Tower to the Schoolhouse: How Scholarship Becomes Common Knowledge in Education.” Twitter: @Edu_Historian.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.