Op-Ed: Fiercely local alt-weeklies are worth fighting for. Can they be saved?

- Share via

Some things that go out of style come back again: mustaches, three-piece suits, absinthe. Others seem gone for good, like boxing on network television, or big family station wagons with a seat in the way back. And some things stick around but get steadily harder to find, so that eventually nobody’s sure if they’re extinct or if one’s left somewhere in the wild. Like the corncob pipe. Or the monocle. Or the alternative weekly.

For those of you who just took off your monocles, arched your eyebrows, and exclaimed, “But what’s an alternative weekly?” I’ll boil it down for you. I’ll tell you what they are (or were). And then, rather than write an obituary, or notes on the chart of a dying patient, I’ll offer some thoughts for how their spirit can live on.

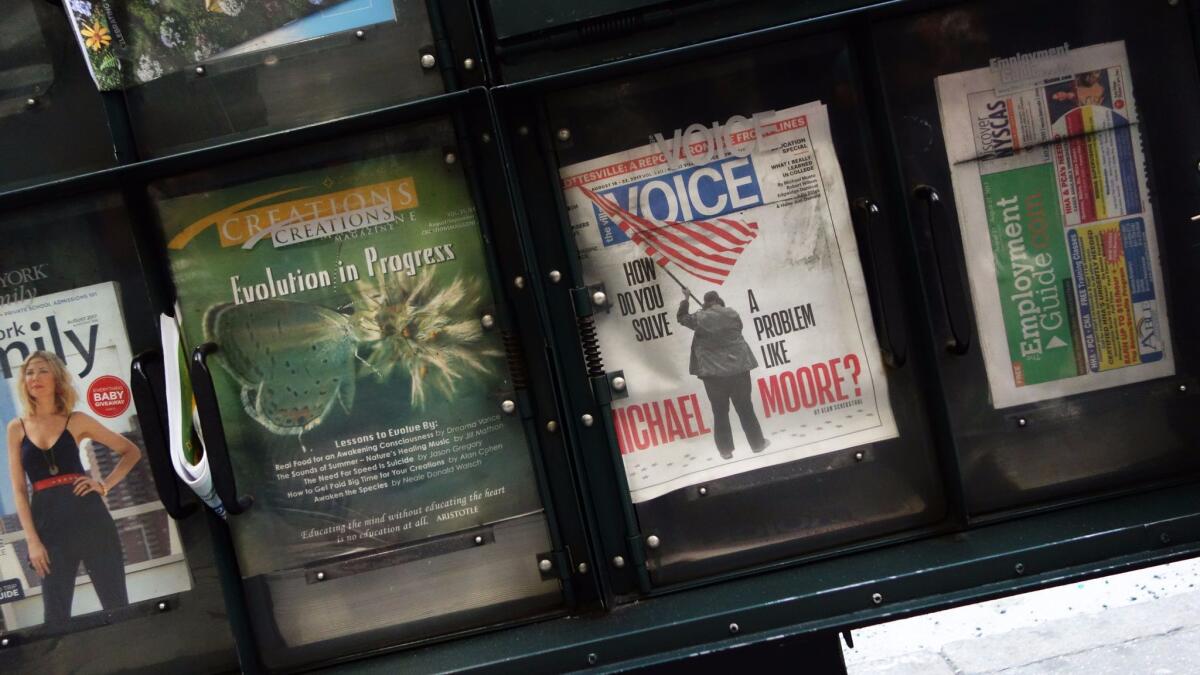

Broadly speaking, “alt weeklies” are (or were) free weekly newspapers, available in health-food stores, bookstores, bus stations and in newspaper boxes on street corners, that — at their best — combined skeptical, investigative political reporting with thorough coverage of the local arts scene. Free + local politics + local arts. Some alt weeklies charged, some of the time, and each had its own editorial mix, but basically that was the formula.

I’m arguing for the alt weekly as a source of inspiration.

The revenue model was simple. Before the internet, alt weeklies had robust classified-ad sections, where you went to find an apartment, which made them the first read for hayseeds new to the city. Those classified ads were also where you went to find women, and men, who would escort, or “massage,” you. (At the New Haven Advocate, where I was editor from 2004 to 2006, prostitutes came to the reception desk to pay for their classified ads in cash.)

In their coverage, alt weeklies were less squeamish about sex and drugs and swearing than the daily newspapers. They were also less reverent toward local politicians, plutocrats and grandees.

That freedom is one reason so many fine writers learned their craft at alt weeklies. The critic James Wolcott got his first gig at the Village Voice, in New York City. Susan Orlean (“The Orchid Thief”) began at the Willamette Week, in Portland, Ore. Political writer Joe Klein (“Primary Colors”) started at the Real Paper, in Boston. LA Weekly can claim food critic Jonathan Gold and Hollywood blogger Nikki Finke.

I could go on.

But when all the ads for sex and real estate went to the web and “weekly” came to mean “irrelevant,” the music stopped.

The Village Voice ended its print edition recently. The Boston Phoenix had its wake in 2013. The New Haven Advocate got a name change and a bad redesign, and I’m not sure if whatever it’s now called still exists.

An honorable death may be preferable to what could happen to LA Weekly, which was just sold to new owners, a group of Republican donors and activists who have laid off nine of 13 editorial staffers and seem poised to rely on low-paid freelancers and unpaid contributors. Or City Paper, in Washington, D.C., which may be sold to conservative talk-show host Armstrong Williams.

These alt weeklies were not, as nostalgians like to think, reliable left-wing institutions. In their heyday they were quite profitable and their owners were fallible, sometimes hypocritical, championing unions for everyone but their own staffs. They either endorsed, or made their peace with, a libertarian spirit that took money and didn’t ask questions. (As an editor, I never wondered about the human costs of the sex trade that filled our classified section.)

But alt weeklies were fiercely local. We ran magazine-length stories on neighborhood figures. We thought an art opening downtown mattered more than high school soccer in the suburbs. We caught the errors of daily newspapers and called them out on their biases. We were necessary.

And I think the original alt-weekly formula I named above — free + local politics + local arts — got a lot right, and is worth preserving in some form. So what should that new form look like?

To begin, it should still be free, and it should take the no-commitment, easy-access spirit even further — with home delivery. I read clothing catalogs while I’m slurping my Rice Chex — I’d surely read a good alt weekly that came in the mail. Bonus: the return of the paperboy (and -girl).

In the alt weekly of the future, local politics should be as local as can be: alt weeklies traditionally focused on City Hall, but today I crave neighborhood news that doesn’t come from parent gossip at school pick-up. News of my block would seem very alternative today.

By the time most of these weeklies die, they look like relics: old newsprint-y tabloids last redesigned back when they were profitable. Any reincarnation would, first, have to be a piece of art, something people want to hold.

Do I know how to pay for the magical product? I don’t. I’m just arguing for the alt weekly as a source of inspiration. Many of us are tiring of social media and despairing about city dailies. As we wonder what comes next, we should keep in mind what came last.

Mark Oppenheimer, a contributing writer to Opinion, is the host of the podcast Unorthodox, the podcast of Tablet magazine.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion or Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.