Opinion: Death for Boston Marathon bomber Dzhokhar Tsarnaev? It’s not the victims’ call

- Share via

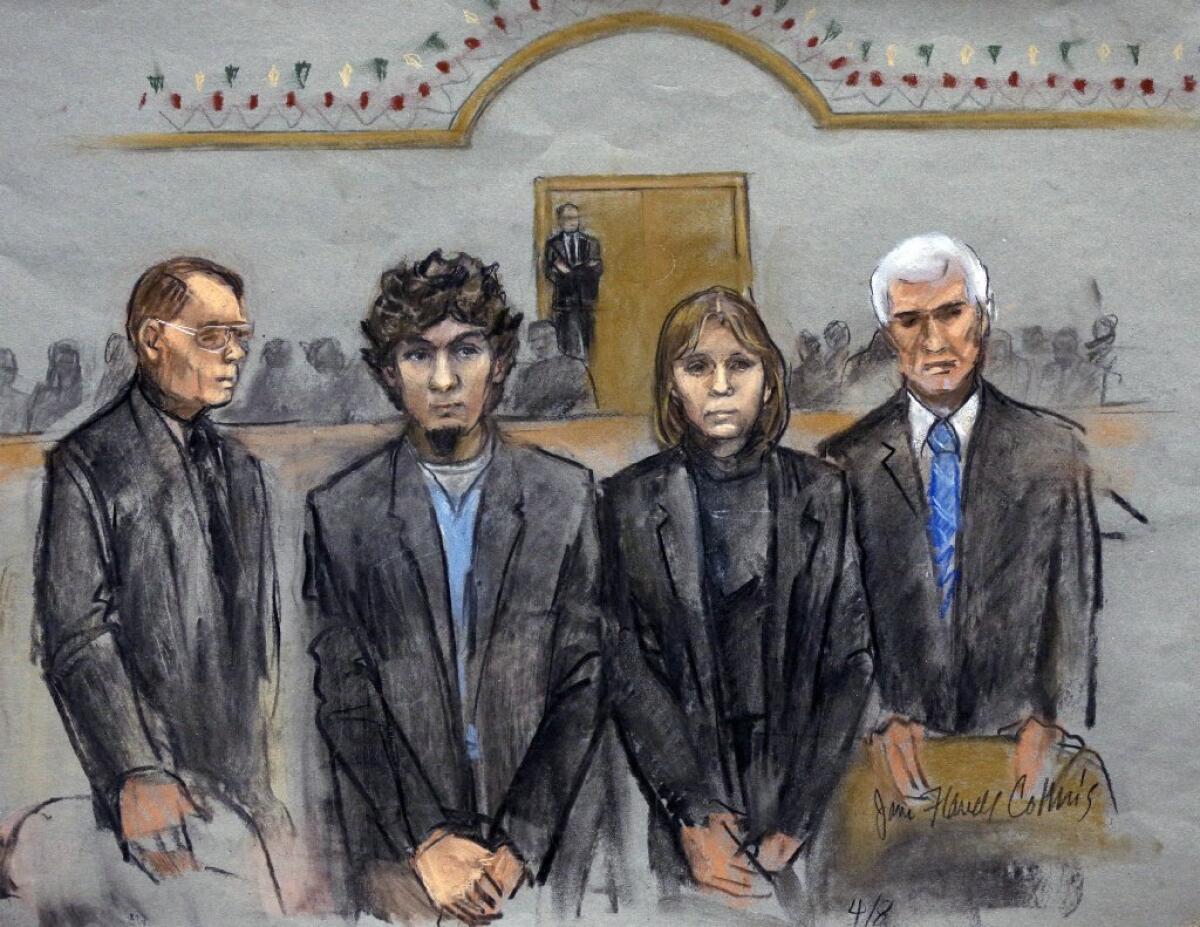

A federal jury in Boston will soon decide whether to sentence Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, the surviving Boston Marathon bomber, to death. Lots of people have opinions on this question, including the editorial board of this newspaper, which reiterated its view that no crime, including this one, warrants the death penalty.

Now the parents of an 8-year-old boy killed in the terrorist act have asked the U.S. attorney to take the death penalty off the table.

In an essay published in the Boston Globe, Bill and Denise Richard -- whose son, Martin, was killed and whose daughter, Jane, lost her leg -- said that a death sentence for Tsarnaev would keep him “in the spotlight” and give the Richards “no choice but to live a story told on his terms, not ours. The minute the defendant fades from our newspapers and TV screens is the minute we begin the process of rebuilding our lives and our family.”

It’s a powerful appeal, but federal prosecutors should ignore it. It would be equally wrong for the government to seek the death penalty because the family endorsed it.

If this sounds unfeeling, it’s probably because of the increasingly prevalent view that the purpose of the criminal justice system is to avenge private wrongs and provide closure for crime victims and their families.

That idea has been encouraged by the rise of a victims’ rights movement and the tendency of legislators to portray new criminal laws as responses to individual injustices -- the “Megan’s Law” phenomenon. (I wrote about such laws here.)

Some of what the victims’ rights movement has achieved is perfectly defensible. The federal Crime Victims’ Rights Act, similar to some state statutes, requires that crime victims be protected from the accused and that they be given timely notice of court proceedings or the release or escape of the accused.

But the law also confers on crime victims the “right to be reasonably heard at any public proceeding in the district court involving release, plea, sentencing, or any parole proceeding” -- a guarantee some victims’ rights groups want to add to the U.S. Constitution.

This is much more problematic. Obviously, victims of crime should be treated with respect, and they have a legitimate stake in the vigorous prosecution of those who harmed them. True, one purpose of the criminal justice system is to eliminate the need -- and the justification -- for private vengeance. But crimes are also crimes against society in general.

The prosecutor at a criminal trial represents the public, not just the victim. That’s why criminal cases in California are styled “The People v. [Defendant]” and why the federal indictment against Tsarnaev was captioned “United States of America v. Dzhokhar A. Tsarnaev,” not “Bill and Denise Richard v. Tsarnaev.”

When U.S. Attorney General Eric H. Holder Jr. announced last year that the government would seek the death penalty in this case, he cited the “nature of the conduct at issue and the resultant harm.” Right or wrong, that was his call, not that of the victims’ families.

Follow Michael McGough on Twitter @MichaelMcGough3

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.