Salesian High’s volleyball team is playing above its head

- Share via

A troublesome thought found its way to Erwin Ramirez just before the championship match, as if sailing on currents of warm air inside the gymnasium, carried by the cheers of the crowd.

How are we going to pull this one out?

It wasn’t the first time he and the rest of the Salesian High team had felt like underdogs.

They seemed all wrong for volleyball, too short, most of them Latino kids from East L.A., where people don’t grow up around the game. Their coach, a black math teacher, learned the basics by reading library books.

Though the Mustangs had built a respectable program on sweat and guile -- the court as a geometry puzzle, footwork like a ballroom dance -- they inevitably drew glances.

“All the other teams are a bunch of white guys,” said Erwin, who stands no more than 5 feet 9, even with his hair cut in a high-top fade. “Everybody’s taller than me.”

Now, venturing to suburban Orange County for a shot at the title, Salesian faced volleyball royalty in the form of St. Margaret’s of San Juan Capistrano.

Big kids from a beach town. A team that had Karch Kiraly, a legend in the sport, coaching two of his sons on the roster.

As the match began, Salesian struggled to control both nerves and a ball that knuckled in the heat. The Mustangs eked out a win in the first set, then lost the second.

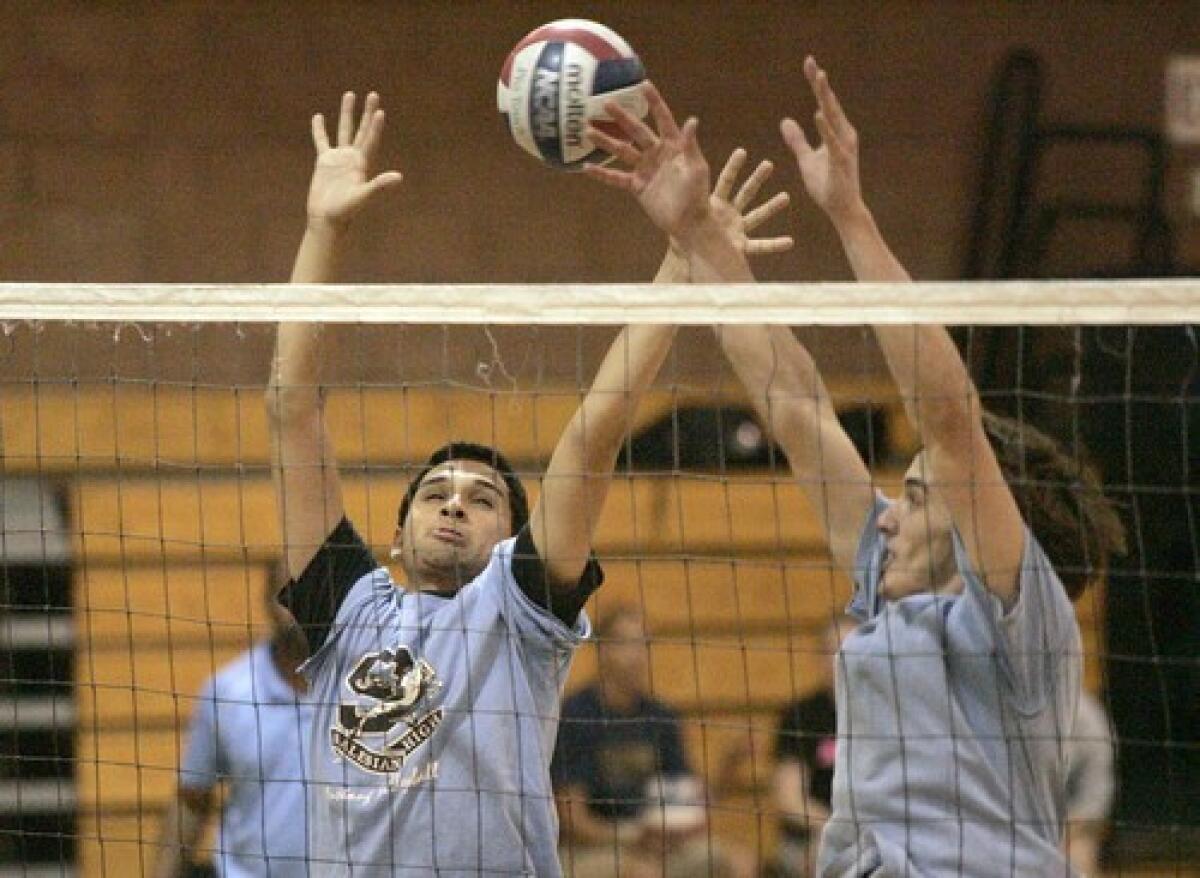

With momentum slipping away, Erwin needed to be sharper with his passes, and Bernard Luna -- at 6 feet 4, one of Salesian’s few tall players -- had to get settled at the net.

“You’re just trying to find a vibe,” the lanky hitter said.

But the score was only part of the story that day. When people talk about Salesian’s run at the championship, they talk about an unlikely coach and a group of young men for whom volleyball has become more than a game.

::

Elliott Walker might be the last person in the room you’d figure for a volleyball coach. His compact body and beard don’t fit the stereotype. But watch the 42-year-old conduct practice, alert to each detail, striding onto the court when a hitter misfires.

“Niño,” he barks, putting a hand on the kid’s shoulder. “This way.”

Right step, crossover left, right again -- they do the footwork together, over and over.

“How do we win?” Walker calls out.

His history with the sport began casually, with family picnics in the 1980s. As a high school student, he volunteered to help with gym classes at Santa Isabel Elementary in Boyle Heights and the principal asked him to coach the girls’ team.

It seemed easy enough until Santa Isabel ran into a squad that knew how to pass, set and hit. Walker realized: Oh, there’s more to this game.

An avid reader, he turned to the library. There, books by Pepperdine Coach Marv Dunphy and UCLA’s Al Scates espoused tactics that appealed to a young man whose interests reached beyond sports to math and science.

“That’s how it started,” he said.

In the years that followed, Walker graduated from college and taught at Santa Isabel. Until he started a boys’ team, only girls played volleyball in East L.A.

Salesian hired him in 1995 and he has become a fixture at the small Catholic school, also in Boyle Heights. He took a break for graduate studies before returning this season, asking fellow math teacher Wayne Teng to be his co-coach.

“It’s very, very difficult to develop a volleyball culture where there hasn’t been any,” said Dunphy, who has watched from Pepperdine and calls Salesian “one of the great stories in our sport today.”

Though Walker preaches devotion -- practices run long and players are encouraged to join his club team in the off-season -- something else shapes his coaching style: memories of those boyhood picnics.

“A lot of my kids come from homes that are dysfunctional or maybe the parents work two jobs or there’s no dad,” he said. “They want to belong to something.”

When team members come across one another between classes, they embrace. When a player slumps off the court during workouts, exhausted from running sideline to sideline, a teammate holds him up until he recovers.

Family means everything to Walker, a single father who has a 12-year-old daughter and has served as legal custodian to several children from troubled backgrounds, adopting a boy named Cameron who now plays for him.

His team calls him “Pop,” and he responds with “son” or “m’hijo.”

“If you’re having a hard day,” Bernard said, “he’ll come by and sit next to you and just talk.”

Go back to that practice when the hitter struggled with his right-left-right footwork. It was late, the team weary, and no one cheered when the kid finally hit a clean spike.

Walker charged back onto the court: “We just got a good hit, so what do we do?”

The players nodded and gathered for a huddle that resembled nothing if not a group hug.

To call Salesian an overnight success would be wrong. The Mustangs had long dominated their league of parochial schools and ventured into the playoffs in seasons past.

But they had always fallen short of the big prize -- a division championship -- and when this spring began with a string of non-league losses, some on the team grew frustrated.

Erwin recalls looking around at practice one day, glancing at fellow starters Jacob Porter and Aaron Turcios, who were about his size. An old doubt resurfaced: He wondered what they were doing in a sport where many of the best players stand 6 feet 4 and taller.

The Salesian roster mirrors a student body that is 96% Latino, and few of the kids played volleyball before arriving as freshmen. Some joined because they noticed the bond among players; others were recruited by Walker. If they balked, worried that volleyball is still considered a girls’ game in their neighborhood, the coach told them: Think of all the girls who will come watch you play.

Salesian compensates for lack of height and experience with a defensive style that emphasizes keeping the ball in play. As Kiraly noted: “They don’t make a lot of mistakes, and they force their opponents to make good plays to beat them.”

The Mustangs also try to throw other teams off-balance with quick transitions.

Most volleyball plays divide into three parts: When a shot crosses the net, the defense must get under it and pass it to the setter, who then lofts the ball to one of several hitters pressing forward on both sides.

The average pass and set take about 2.5 seconds. Salesian tries to shave off precious tenths of a second, giving opponents less time to settle defensively.

This approach suits their coach who, ever the mathematician, asks players to line up with shoulders angled just so, teaching them precise steps for each situation. Hitters aim at nine distinct areas across the net like keys on a cellphone, beginning with high-percentage shots to No. 1, then No. 3, and so on.

“We know how to place the ball and we know how to work it,” Cameron said. “You have to think your way through the match.”

As the setter, Erwin must analyze the defense and pass to the hitter with the best shot. He has learned to stop worrying about height.

The turning point came at midseason when the soft-spoken Bernard took command, leading Salesian to third place in a Las Vegas tournament. The Mustangs swept through their league schedule, then opened the playoffs against an overmatched opponent.

Walker began pulling his starters to give the reserves a chance, but Aaron Turcios hesitated.

“Pop,” he said, “you can’t take me out.”

“Why not?”

“My dad’s here.”

The Turcios family lives in Watts, in a tidy house where roses grow along a chain-link fence and Rafael Turcios greets a visitor from behind a steel security door.

“This neighborhood is not terrible,” the El Salvador native says. “But not so good.”

To pay for their son’s education, Rafael works in a machine shop and his wife, Maria, cleans houses. They were not thrilled when Aaron joined the volleyball team.

“The sports take a little from school,” Rafael said. “They are practicing every day.”

Mom said let him play. Dad refused to attend games and wanted his son to quit. When Aaron’s grades dipped, the arguments grew more heated.

“He kept asking me why I was wasting my time,” Aaron said.

Other parents at Salesian are more supportive. They clap loudly at games and join the team in call-and-response chants. They yell “gooaall!” -- the soccer cheer -- when opponents hit the ball into the net.

“We’re going to get under your skin,” said Bella Fernandez, who is Erwin’s mother.

Walker tries to allay any fears that volleyball will pose a distraction by requiring his players to attend study hall before practice. Erwin, a junior, is an honors student, and all nine of the team’s seniors are headed to a university this fall. Jacob will go to New Mexico State, for example, and Ronald Quintero will attend Boston College. Bernard’s stellar play earned him an athletic scholarship to Hope International University in Fullerton.

In the Turcios’ home, the situation improved after Aaron got accepted to San Diego State. When Walker found out that Rafael had finally showed up at a game, he quickly put Aaron -- a defensive specialist -- back on the court.

“The kid played his heart out,” he recalled.

As Salesian closed in on a victory, Aaron looked into the stands and noticed his father smiling. He was too far away to see the tears in Rafael’s eyes.

With the best-of-five match against St. Margaret’s tied, Salesian settled down and began to find a rhythm, calling out hitters, directing one another on defense.

The Mustangs won a close third set and -- just that quickly -- spotted a change in the team across the net.

“They’re breaking!” Jacob yelled. “They’re breaking!”

The opposing fans weren’t as loud now, not with Salesian opening an eight-point lead in the fourth set. Still, the players faced some daunting history. Twice before, they had reached the division championship. Twice they had lost. Bernard kept thinking: We’re not done yet.

Each time St. Margaret’s scored, the Mustangs answered to maintain their cushion. Finally, at match point, they showed a fake front and Cameron passed to Bernard, who came soaring from the back line, crushing a shot that ricocheted off a defender and fell to the floor.

The Salesian players dog-piled on the court as Bernard raised his arms and hollered. In the stands, the normally raucous Bella Fernandez could not manage a peep.

“I couldn’t breathe,” she said. “I couldn’t stop crying.”

Even a disappointed Kiraly appreciated the moment, saying later: “I like to see volleyball grow and thrive in areas where you might not expect it.”

Two weeks passed before the Mustangs reconvened on campus, several players stopping by an office where their championship plaque lay on the table. They took turns picking it up, some kissing it, others running their fingers across the lettering. Erwin used his sleeve to rub away the smudges.

“We had so much to prove,” he said.

Walker wanted more, wanted his players to grasp the wisdom they had gained along the way. Perseverance and camaraderie, things like that. Aaron said he learned to always be on time for his job at an ice cream shop.

School was out for the summer and a warm night beckoned. With almost two months before the next club match, the team had earned a break, but no one left early.

The Mustangs walked back across the courtyard to the gym for the start of another long practice, scrambling and diving for every ball. All those rubber-soled shoes scuffled across the hardwood, a squeaky kind of music echoing off the walls.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.