NCAA grants Power Five conferences more autonomy

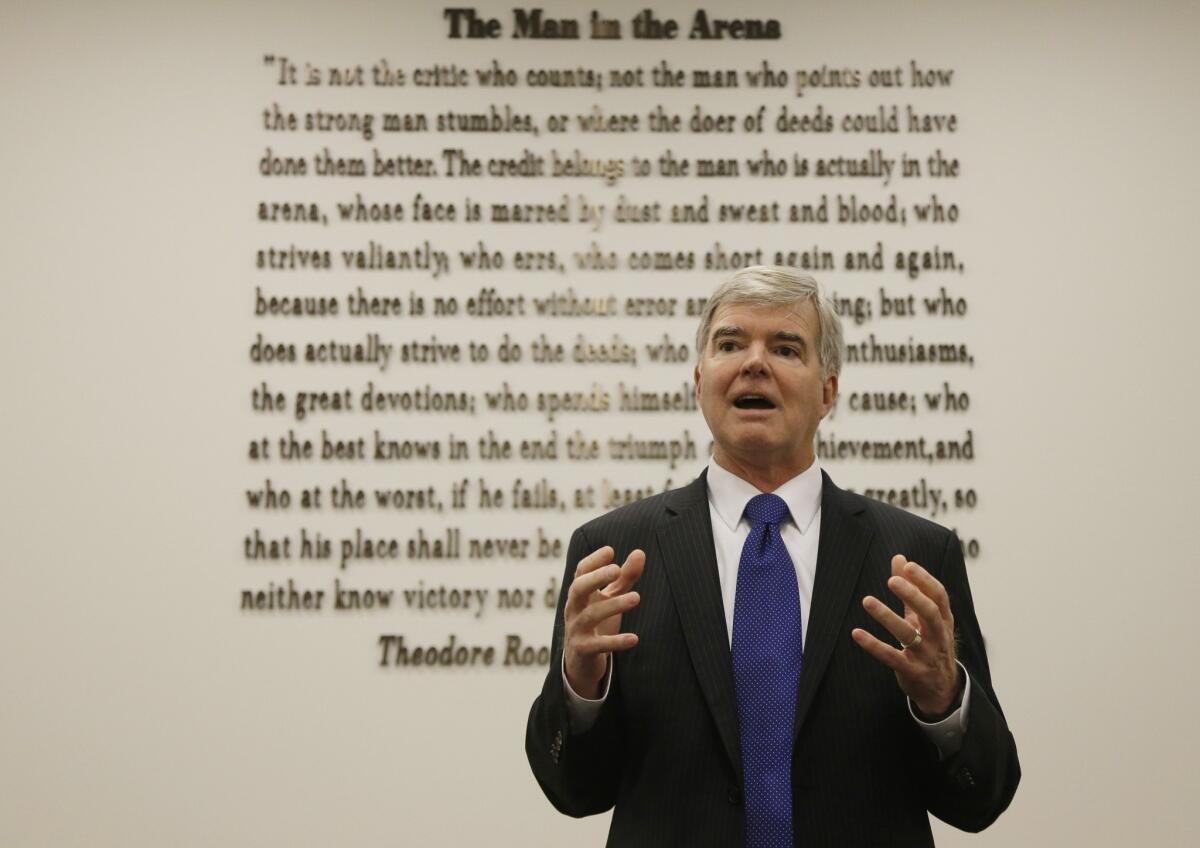

NCAA President Mark Emmert speaks at the organizations headquarters in Indianapolis where the NCAA Board of Directors approved reforms that will allow the Big Five power conferences to pass legislation without approval of the full NCAA membership.

- Share via

The NCAA board of directors voted Thursday to grant the five wealthiest college football conferences more freedom to pass legislation without approval of the full NCAA membership.

Although the outcome was widely anticipated, the 16-2 decision conducted at NCAA headquarters in Indianapolis is subject to a 60-day veto period but is not expected to be overridden.

The 65 schools representing the Pac-12, Southeastern, Big Ten, Big 12 and Atlantic Coast conferences had threatened to form their own division if not granted more autonomy.

These “Power Five” leagues had grown frustrated by being overruled by the larger Division I membership of 351 schools.

Thanks to huge football television deals and other revenue streams, the richest leagues have pocketed a disproportional amount of money but lacked the muscle to use the funds as they saw fit.

Thursday’s vote grants the Power Five twice as much voting power (37.5%) on one of the NCAA’s newly created councils. The five remaining major football conferences will have 18.5%, while subdivision football and non-football schools will share 37.5%. Athletes and faculty members would have the remaining share.

NCAA President Mark Emmert generously called the vote “a compromise on all sides that will better serve our members.”

Immediately, Thursday’s NCAA vote allows the Power Five to move forward on legislation to offer “full cost of attendance” to athletes. Full cost is a federally established figure that calculates the cost of college education beyond tuition and board (incidental expenses a normal student might incur). The proposed stipend would raise current athletic scholarships to that threshold.

Pac-12 Commissioner Larry Scott anticipates stipends at his schools will annually range from $2,000 to $5,000 per student.

The amount will be paid over the course of the nine-month academic calendar and will vary as each school calculates its full cost in accordance with federal guidelines.

Factors such as demographics will be considered. It costs more to live in Los Angeles than Pullman, Wash., so an athlete at UCLA might receive more than an athlete at Washington State.

“It is complicated,” Scott said about how the stipend would be calculated. “And if it’s different on each campus, so what? The value of your tuition is different on each campus. There are all kinds of competitive differences. The types of facilities you’ve got, the coach you got, the city that you’re in, the value of your housing, the value of your scholarship. I think it’s got to go that way.”

Scott said details must be worked out over the next few months but he expects “full cost” will be approved at January’s NCAA Convention in time for the 2015-16 football season.

All 351 schools in Division I would be allowed to offer full cost of attendance. However, the 65 schools from the five money-rich leagues have the advantage of tapping football revenue to pay the stipend. The Pac-12, for example, just signed a 12-year, $3-billion deal with ESPN and Fox.

Non-football-playing schools that compete in Division I in other sports, such as Pepperdine and Loyola Marymount, would have to find other ways to pay for full cost.

Pepperdine Athletic Director Steve Potts said Thursday he welcomed the NCAA vote if only because the alternative would have been worse. “Those in our situation were like, ‘OK, let’s get on with it,’’’ he said.

Potts said the power leagues’ threat to split may have been a negotiating ploy, but the prospect of it happening would have been “tragic” to smaller schools.

He said he won’t know how Pepperdine will deal with full cost until he sees the final proposal. “We know it’s going to cost us more money,” Potts said, adding the plan at Pepperdine will “look like whatever we can afford.”

Resources might have to be reallocated to cover revenue-producing sports (basketball) and female athletes protected by Title IX legislation.

Potts is heartened that the wealthy leagues have promised not to alter scholarship caps that allow Pepperdine to compete at high levels in many non-revenue sports.

The smaller schools have to readjust to the new reality.

“This is life for 300 of us in Division I,” Loyola Marymount Athletic Director William Husak told The Times last spring when the NCAA rule change appeared imminent. “There are the 65 and there are the rest of us.”

The power leagues, however, were tired of being outvoted by the larger, but poorer, membership. Only 128 schools play Division I football, yet 65 of those are from leagues reaping the benefits of huge broadcast revenue streams.

A 2011 proposal by SEC Commissioner Mike Slive calling for a $2,000 annual stipend, per athlete, was rejected by the full NCAA membership.

As a result, Slive and other power commissioners threatened to form their own division, or even leave the NCAA, if they were not granted autonomy on certain issues. Smaller conferences ultimately had little choice but to relent to the power leagues.

“I believe the real work begins now as we see how the five equity conferences manage their newfound ability to approve legislation,” Atlantic 10 Conference Commissioner Bernadette McGlade said in a statement.

The NCAA finds itself in an increasingly defensive mode as it fights credibility issues and legal battles involving player unionization and licensing rights.

Big 12 Commissioner Bob Bowlsby, speaking Wednesday at an NCAA forum, said the Power Five leagues needed to be “a little less magnanimous about the 350 schools and spend a little time worrying about the most severe issues that are troubling our programs among the 65.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.