SCHEUER: AN AISLE SEAT ON HISTORY

- Share via

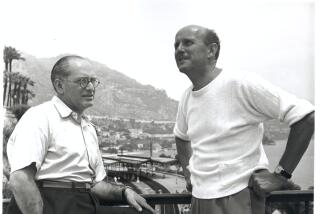

I’ve long since forgotten what the movie was, but it was at the Directors Guild Theater and Phil Scheuer and I, new colleagues at the newspaper at that time, were sitting together, browsing through the production notes before the screening began.

“Running time 90 minutes,” Phil said. “I like it already.”

As the years went on, the wry humor of Phil’s comment has played in mind very often indeed, usually in the late reels of some swollen epic that is taking three hours to say what was probably not worth telling in three minutes.

Phil--Philip K. Scheuer as his byline read--reviewed films for this newspaper from 1927 until he retired in 1967, and he continued to attend screenings until only a little while before he died this week at the age of 82.

His reviewing span--to put symbolic brackets on it--began just before “The Jazz Singer” and lasted until after “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” He had an aisle seat, so to speak, on a time of extraordinary changes in the movies as the art form of this century: from the silents to Sensurround sound, from Ernst Lubitsch to early George Lucas, from the vague dream of television to the competitive reality of television.

In a real sense Phil Scheuer’s Hollywood predeceased him. The Golden Age of the ‘30s and ‘40s, when the studios were truly major--fiefdoms of talent, with rosters of stars and publicity departments the size of the Rams squad--changed beyond recognition in the age of television; less extravagant, less potent, less fun.

The product changed as well, in ways not always to Phil’s liking (he was not alone). He lamented the decline of a certain kind of meticulous craftsmanship, and was grateful when it could be found again, as in David Lean’s “A Passage to India.” He lamented even more the decline of restraint and the corruption of taste, because he was a man of taste.

Comedy based on cheap, heavy-footed jokes left him unlaughing, and his reputation for being hard on comedy after a while raised suspicions in him that the studios were planting hard laughers around him at screenings, employees with low thresholds of hysteria, to generate the impression that a movie was being riotously well received.

At that, it was Phil’s indefatigable love of movies, his fairness, his understanding of the arts of film, his sensitivity to a film’s intentions, his positive standards and his quiet wit that characterized his reviewing. Often, riffling through the brittle and faded clippings to read up on a performer or a film maker from the Scheuer years, you come upon one of his criticisms and recognize all over again what a stylish and entertaining writer he was: decisive and outspoken but never claiming infallibility, and not a killer.

The wonder--and it is a wonder--is that he was able to do it for so long and not have the excitement and the expectation eroded by the disappointments, the flops, the boring, the derivative, the schlock, the surfeit of turkeys.

I suspect that in recent years there’ve been fewer films that he actively enjoyed. The exploitive uses of screen depressed him, but so did what seemed to him a pretentious obscurity. (A friend remembers his struggles with Antonioni’s “Blow Up,” of whose significance in film history he had no doubt, but which struck him as a not very likable foolishness.)

I wish he’d written a memoir and I urged him to do so, but he was both kindly and rather shy, and he found it hard to believe that anyone would want to read about the man behind the byline. The reticence was a measure of the quiet good man he was, an anomaly amidst the newer cult of critical personalities. Yet I think he was wrong, and that his recollected eyewitness to the Hollywood that was would have enriched and instructed us all.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.