‘BAO’: UNLIKELY FATHER, UNLIKELY SON

- Share via

What is most striking about “Bao and His Son” (at the Grande 4-Plex in the Sheraton Grande downtown) is how free from cant it is, when its simple “Stella Dallas”-like story could so easily have been exploited as propaganda. Although it indicts the harshness and unjustness of life for the poor in China in the 1930s, it takes a tragic rather than dogmatic view of human events, and is all the richer for doing so.

This latest offering in the New Films From China series was adapted and directed by Xie Tieli from a 1934 story by Zhang Tianyi, an eminent writer of satire and children’s stories (the author is introduced briefly at the beginning of the film). Bao (Guan Zongxiang) is a doorkeeper for a wealthy family in a town south of the Yangtze River. After 30 years of service he is paid only $7 a month and has been able to afford only three coats in that length of time. Widowed when his son Xiao was 5, Bao struggles mightily to keep the youth (Liu Changwei) in school, even hoping that he will be able to attend university.

Now in high school, Xiao, once a good student, has failed to graduate and must repeat a semester. This in itself provokes a crisis, for the school has changed uniform styles and Bao is hard-pressed to raise the money for a new uniform. None of this affects Xiao very much, for he is badly spoiled by his saintly father and is captivated by the rich kids in his class. Actually, the father is as essentially naive as his son, who’s reached the point where he’s now ashamed of his humble, self-sacrificing parent. For his part, Bao won’t listen to his barber friend’s sensible suggestion that the boy would be better off in a trade school.

“Bao and His Son” is a triumph of detail and nuance. There’s a wonderfully sustained and understated sequence involving Xiao’s visit to a dormitory where his affluent classmates live. He’s awestruck by their closet full of Western clothes, their phonograph, their tiled modern bathroom with its shelf of toiletries, including some hair pomade that absolutely enraptures him. How easily this key sequence could have been staged as an indictment of corrupt Western materialistic values; instead, Tieli invites us to share in the boy’s understandable wonderment, leaving us with the feeling that evil lies not in the rich boys’ possessions (and opportunities), but in how inequitably they were distributed in Chinese society of the time.

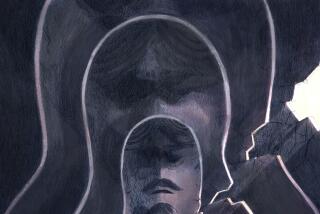

Photographed by Huang Xinyi, “Bao and His Son” (Times-rated: family) has a glowing, textured look with an emphasis on deep shades of blues and grays. Liu Changwei accomplishes the difficult task of inviting us to sympathize with Xiao, suggesting that the youth is essentially decent despite his spoiled, selfish behavior. Likewise Guan Zongxiang, with his polite, deferential smile, shows us that the saint that Bao seems is also human. The reason that he’s making all these sacrifices is succinctly summed up in his rueful gaze at a boy earning his living by sweeping the floor of his friend’s barbershop.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.