Learning to Swim by Graham Swift (Poseidon: $14.95; 189 pp.) : THE SWEET SHOP OWNER (Washington Square: $7.95, paperback; 222 pp.) and SHUTTLECOCK (Washington Square: $6.95, paperback; 219 pp.)

- Share via

Graham Swift is the latest in a long line of English authors to have his prose, presence, popularity and his, for the most part deserved, critical acclaim shoveled into the maw of the insatiable American reading public. In his previous works, “The Sweet Shop Owner,” “Shuttlecock” and the critically acclaimed “Waterland,” Swift flashed concrete and colorful images of murder, childlessness and provincial life before our eyes. Now, in 11 short stories composing “Learning to Swim,” he paints black-and-white scenes of afflicted and maladjusted individuals in illusionary settings dallying with improbable events.

Swift’s first novel, “The Sweet Shop Owner” (published now in the States as a paperback original), was the dysteleologic saga of Willy Chapman--a boorish fellow faced with a rebellious daughter who despises Willy’s superciliousness and anonymity and wishes a respite from the bleakness of their lives. This novel of prophylactic protectiveness and lack of ambition sets the tone for Swift’s future works, including “Shuttlecock” and the highly praised and well-received “Waterland.” The problem for the majority of episodes in “Learning to Swim” is that the stories are neither pure fantasy nor pure emotion, but it is a mixture of the two, as if reality and the absurd could be evenly mixed like oil and water without separating on different levels.

In “Shuttlecock,” Prentis, the narrator, searched for missing elements of police cases involving his father, a World War II hero and legend, only after his father had suffered a breakdown and became incapable of speech. Prentis was a present-day man beset by the problems of a modern world while trying to discover the truth of the past. Throughout “Shuttlecock,” Swift displayed an artful sense of timing and irreverent, mordant humor.

Unfortunately, “Learning to Swim” lacks the brio and zest of “Shuttlecock.” There is too much thought for thought’s sake and not enough action. In “Hoffmeir’s Antelope,” Uncle Walter--a recently widowed zookeeper with a weakness for Guinness who likes to work “with,” not “on” animals--not unsurprisingly disappears at the end of the story with a rare antelope. Swift lures and entices us somewhat with the colorful eccentricities of the doddering animal attendant, but it is not enough to sustain the reader’s interest.

The title story of the collection, “Learning to Swim,” portrays the struggle between sniveling parents for the affection of their son at holiday on a beach in Cornwall. The boy thrashes out, swimming away at the end; but, too predictably, all of the family learn to endure and survive.

Swift’s use of language is sometimes trite, at other times contrived. Would teen-age boys viewing a lovers’ tryst refer to naked breasts as “two white, sunlit, pink-flowered globes”? In “The Watch” would a grandson really see “ . . . gloom, humility, pride, remorse, contrition and despair” all in a single look at his grandfather’s face?

Glimmers and slivers here remind us of what Graham Swift is capable of. Regrettably, they are too few and far between to save “Learning to Swim” from drowning in its own blandness.

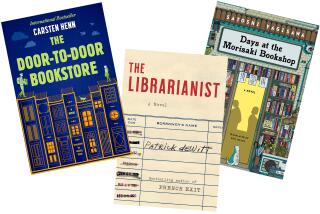

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.