Laughing at Apocalypse : In ‘Nuclear War,’ the End of the World Is in the Cards

- Share via

The “war room” in Irvine began sending nasty messages over the computer network’s electronic mail system shortly after midnight.

To Battle Creek, Mich.: “Dear Tony the Tiger. Hope you ate your Frosted Flakes!! It’s your last meal!!” From: Doug Malewicki, inventor.

To Little Rock, Ark.: “Ya awl will be happy to know yur town will shortly be renamed Littler Rock. There just ain’t goin to be much left of it after we uns is dun wid u.” From: the Irvine Tachtical Wheapons Teem.” To Chicago, Ill.: “Greetings from the granola yuppies of California. One way for us to get more needed water is to vaporize your Lake Michigan for more rain.” From: Doug Malewicki, inventor.

8:10 a.m. Saturday: Day one of “The Day Before,” the third annual nationwide Nuclear War card game tournament, is now into its third hour.

Hunkered down in their “bunker”--a cluttered office in Doug Malewicki’s Irvine tract house--Malewicki and three other men are reaping the results of their pre-game tomfoolery eight hours earlier.

The first round of moves made by the 20 teams scattered across the country came over the computer screen at 7:40 from tournament headquarters in Scottsdale, Ariz. Although no bombs had been dropped on them by any of the other teams, the results of the first round did not constitute good news for the Irvine team.

Goodwill, Okla. played a “secret card” on them (“You have tricked the enemy into an ineffective but time-consuming Summit Talk”), which will cause them to lose a turn. Lawton, Okla. also played a secret card on them, causing two million of Irvine’s people to defect to another country. And, as a result of “propaganda cards” played on them by Lawton; Austin, Tex.; Enid, Okla.; and Little Rock, Ark., Irvine lost another 25 million people.

“We started with 48 million people and we’re down to 21 million already,” explained Malewicki, who invented the Nuclear War card game in his spare time 21 years ago. “As soon as I write down ‘Malewicki, inventor’ (on a message), people like to start zapping you.”

“Some of these guys,” he commented to a recently arrived visitor, “are playing this game seriously.”

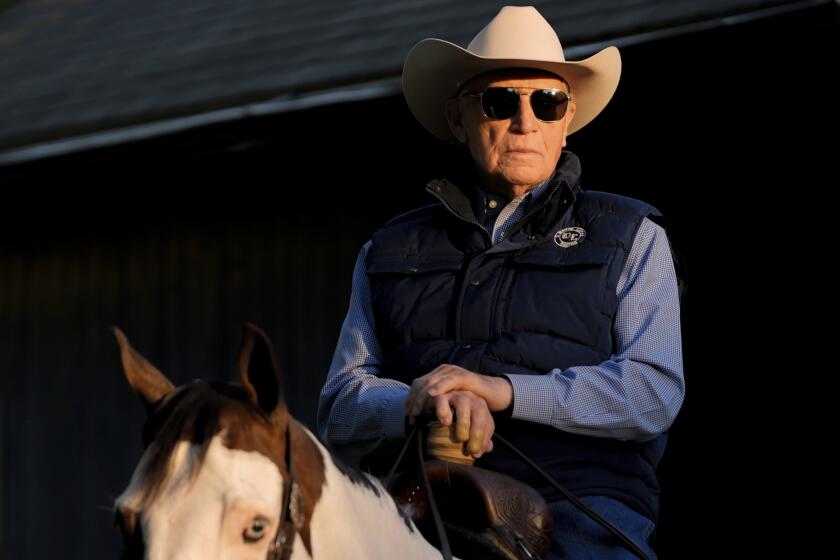

For Malewicki, a 47-year-old aerospace engineer, the game--and the annual tournament it has spawned--is just as it was meant to be: all in fun.

Others contacted by The Times were somewhat less enthusiastic about a game based on nuclear war.

“My only impression (of the game) is that it’s basically escapism,” said Tim Carpenter, field director for the Great Peace March, who had not heard of the game. “I can understand (that), but I would hope people would spend that energy and time concretely working to build a world beyond war and a nuclear free future.”

Marion Pack, director of the Orange County office of Alliance For Survival, said she’d “heard of a couple of games possibly similar to it but not this one.

“If there are winners (in the game) through the use of nuclear weapons then that would be unrealistic because there will be no winners from nuclear war,” said the director of the Southern California-based anti-nuclear education organization. “If the end result is people see the need for diplomatic solutions to the problems we’re dealing with, that would be beneficial because we know the answer is improved relations between all the world’s nations because we’re all living under the threat.”

But at the “Day Before” bunker in Irvine, mutual trust and diplomacy were not the tools of the hour.

Indeed, despite their heavy losses in the first round, Malewicki and company laughed like fraternity house pranksters as Mike Ryder, a 28-year-old commercial pilot from Encino, typed out a computer message to Pasadena which they had “zapped” in the first round of play with “Super Germ,” a germ warfare card that destroyed 25 million of Pasadena’s people.

“This guy in Pasadena is trying to set up this California alliance,” explained Ryder with a mischievous grin, “and we just said the hell with it, and we’re wasting him,”

But that’s not what they were telling their neighbor to the north: “Dear Pasadena, our apologies. Super Germ was definitely not intended for you . . . California for a better tomorrow. Your friends in Irvine,” Ryder wrote.

Malewicki and his fellow nuclear warriors laughed and retreated to the kitchen for pretzels and corn chips.

Despite the early hour, it was appropriate fare for playing what Adventure Gaming magazine calls “the quintessential beer and pretzels game.”

Flying Buffalo Inc. (FBI) of Scottsdale, the maker of Nuclear War, describes it simply as a “fast-paced comical card game in which the object is to be the sole survivor of a nuclear exchange.”

Since Flying Buffalo owner Rick Loomis bought the exclusive licensing rights to Nuclear War from Malewicki in 1972, he has sold an estimated 60,000 copies of the $14.95 card game through toy and hobby stores. It comes with two decks of cards and a spinner (the arrow lands on such categories as “Dud Warhead (no effect), “Bomb Shelters Save 2 Million” and “Radioactive Fallout Kills Another 2 Million”).

As its survival on game store shelves indicates, Nuclear War has become something of a cult favorite among its small but growing legion of players.

During a game convention in Houston in 1983, a midnight Nuclear War tournament for “100 warm bodies, preferably in costume” lasted until 7:30 in the morning. Players showed up dressed as “radioactive mutants” and “alien frogs,” and Malewicki himself made a personal appearance, arriving in a wheelchair and dressed in black as Dr. Strangelove.

But Nuclear War card game players have been known to crop up in far less likely places. A few years ago, Air Force Maj. Ronald “Dutch” Blake and a group of officers regularly played the game in a top secret vault at the Pentagon during their lunch breaks. “One of my young lieutenants had played before and got us playing it,” says Blake, now retired and living in Lakewood. “I enjoy just about any form of competitive gaming.”

Of course, a game proclaiming to be “a comical cataclysmic card game of global destruction!” is also bound to generate controversy. The game reportedly was denounced as “disgusting and offensive” by an anti-nuclear member of Britain’s Labor Party who unsuccessfully tried to ban the game in Britain.

“Just the subject obviously sets some people off,” acknowledged Loomis in a telephone interview the day before “The Day Before.” His response to any of the doomsday game’s naysayers: “It’s just a game.”

“It makes fun of a serious subject,” Loomis allows, “but it’s a subject that’s too serious to be taken too seriously. You’ve got to stick a little humor in there or it’s just too much.”

Bob Westal of West Los Angeles, a member of Alliance for Survival who has played the game with friends, is less than comfortable with the effect the game might have on some people.

“I had a very mixed reaction to it,” said Westal, 24, a former film student. “It forces us to confront certain realities. The cards have kind of a black humor to them, that I appreciate, showing the irrationality of foreign policy. The only bad part of it to me is that when you deal with something like this there’s always a sense of desensitization. There is a certain coldness to the game that kind of disturbed me.”

“I think,” Westal added, “it also depends on what you bring to it. I think for people like me (in the peace movment) it brings about the right effect. But there’s a certain kind of person that might go away with the wrong things.”

In its own way, Loomis maintains, the Nuclear War card game is an education in the folly of nuclear war: “One thing about it is that this is the only game I’m aware of where everybody can lose and you finish up without a winner,” he said. “Obviously, it (a real nuclear war) is not something you want to start and get involved in.

“I’d suggest also that if anybody complains after playing it, they haven’t got a sense of humor. “ (possible cut)

“There are,” he added, “a whole bunch of secret cards interspersed in the deck kind of like chance cards like ‘Your president gave a boring speech, you lose a turn.”’

Inventor Malewicki pointed out that “there are lots of war board games” available on the market. But, he said, although games based on past wars or on futuristic space wars “are okay, the current thing (nuclear war) is a little touchy.”

The original Nuclear War game Malewicki created in 1963 was a far cry from the satirical version of today.

Malewicki, who at the time was an engineer at Lockheed Missiles and Space Company in Sunnyvale and working half time on his masters degree at Stanford University, said the early version was a “serious” strategy board game complete with moving pieces in the shape of scale model missiles and airplanes.

Malewicki said the Lockheed patent office “liked the game” and tried to market it to major game manufacturers, who promptly turned it down. “It was just too controversial then,” he said.

After leaving Lockheed and going to work on the Apollo space project at Rockwell International Space Division in Downey, Malewicki redesigned the game and began producing it himself in 1965. Although he sold all 3,000 copies, Malewicki said he dropped out of the game business when he realized he was making only about 25 cents an hour for his efforts. (Copies of the original $3.25 games, he noted, are now collectors items selling for $100 each).

For the next few years, Malewicki largely forgot about what he calls his “stupid game.” (possible cut)

Aware of the out-of-print game’s small but loyal following among gamers, Loomis tracked down Malewicki in 1972. Malewicki, who now averages several hundred dollars a month in royalty payments, is amazed that since Loomis began reissuing the game “it somehow caught on. Don’t ask me how.”

Because of Nuclear War’s antiquated arsenal of B-70 bombers and Atlas and Polaris missiles, Loomis in 1984 began producing an updated, spin-off card game called Nuclear Escalation which features Star Wars-style killer satellites and orbiting missile bases. But Nuclear War is still the Coke classic of its genre, with game outlets selling about 6,000 copies a year, according to Loomis.

With the popularity of home computers, it was only natural that a Nuclear War tournament would be played electronically over a computer network, in this case both CompuServe and MCI Mail.

On April 14, 1984, Loomis conducted the first annual “The Day Before” Nuclear War tournament with teams playing in 18 cities. (The tournament was so named, he explained, as both a play on words on the TV-movie “The Day After” which dramatized the aftermath of a nuclear exchange, and also because the first tournament was held the day before the deadline for filing income tax returns).

“The Day Before” may also hold the distinction of being the only game tournament in which there has so far been no winners. Says Loomis: “Everybody got blown up both times.”

For the first two tournaments, Loomis said, “it was all done over the (computer) networks, but we shuffled the cards here (in Arizona), dealt them out and laid them on the table. This year we’ve written a computer program to shuffle and deal the cards automatically so we don’t have to do that. That saves considerable time.”

Still, he said, there is no telling how long the tournament may last. With only about seven-hour breaks for sleep at night, he said, “The first year we finished about 1 or 2 o’clock on Sunday afternoon. The second year the world ended on 10 a.m. Sunday.”

(possible cut)

Because there were no winners the first two years, Loomis said, “We sent the trophies off to the last surviving groups--the ones that died last”: Toledo, Ohio, the first year; and Santa Ana the second year.

During a lull in the tournament on Saturday, some of the players provided a status report on how they had survived the first round of the tournament.

“Everybody kind of left me alone the first round,” Barb Baser said by telephone from Detroit. The 38-year-old office manager for a computer software firm whose computer “handle” is Ms. Wiz, is a veteran of the first two Nuclear War tournaments.

“Normally,” she said, “I use the strategy of leaving everybody else alone and doing nonaggressive type things and I normally last just about the whole game.”

Cliff Mertins of Jacksonville, Fla., who has played the Nuclear War card game since 1978 and who also played in the first two tournaments, said he and his friends made it through the first round unscathed.

“I played a propaganda card on Pasadena for 10 million people, and I also played a secret card on Pasadena and knocked them out for a turn,” Mertins said, explaining the reasons behind his tactics: “I think they played last year and they wiped me out of the game.”

Nevertheless, he said, he went after Washington D.C. instead of Pasadena on the second turn “just because I really didn’t want to be the person to put them (Pasadena) out (of the game).” Referring to the $30-per-team fee that Flying Buffalo charges to finance the tournament, he added, “I know I’d be a little upset if three or four people ganged up on me and put me out in the second turn.”

As for “the morality of pretending to destroy cities,” Mertins said, “if you can’t play this game with a laugh you shouldn’t be playing it. Anybody that takes this game seriously must be on drugs. It’s basically just a good time game.”

Arthur Rubin of the Pasadena team, who lost 35 million people in the first round thanks to Jacksonville and Irvine, agrees.

“Maybe,” said the 30-year-old computer programmer, “it’s a way of laughing at nuclear war.”

Malewicki, who was participating in his first Nuclear War tournament, said he can’t explain the game’s popularity. In fact, he acknowledged, he is both surprised and pleased the game is still around.

“Oh yeah, I love it; I like getting my little (royalty) checks,” he said in his kitchen during a lull in the action. Money aside, he added, “Even though it’s a stupid game, to have one of my inventions called ‘quintessential’ is really neat.”

Malewicki was interrupted by a flurry of activity in the “war room.” It was 9:40 a.m.

“Someone just Super Germed us!” reported Frank Hines, a 24-year-old computer systems analyst from Encino. “Little Rock did it.”

The dreaded Super Germ card wipes out 25 million people. But because Irvine had only 21 million people left after the first round, Malewicki announced the inevitable: “We’re out.”

Back in the “war room,” he and his team mates planned their final retaliation.

“Let’s drop 10 megatons on Pasadena--then we’ll apologize,” suggested Malewicki, adding with a grin: “If we hadn’t insulted everyone last night, we’d probably still be in the game.”

“The Day Before,” a postscipt: By Wednesday morning, the tournament was dragging into its fifth day of play, with 17 teams down and three to go: Chicago, Detroit and Enid, Okla.

Because most players are working, they are now doing only two turns a day, said Loomis, who admitted he didn’t expect the tournament to last this long.

“There’s a good chance (Chicago and Enid) will finish off Detroit with their final retaliation, then we’ll be down to two,” he said. “And after that, maybe there will be four more turns. My prediction is that Chicago is going to win.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.