A Dream Come True--With One Reservation

- Share via

BOSTON — My dad called me from work and said, “Lenny’s dead, Lenny’s dead.”

“No, you’re lying,” I said. “You got to be playing.”

“Lenny’s dead,” he said. “Lenny’s dead. He died, man. Lenny’s dead.”

I just dropped the phone and ran outside. We got woods behind the house, and I just ran over the fields. I just couldn’t believe it.

I remember it like it was yesterday.

--ADRIAN BRANCH

If, perchance, today’s third game of the National Basketball Assn. finals proceeds much like the first two, don’t be surprised if the following scene takes place in the fourth quarter.

Adrian Branch of the Lakers--No. 24 on your program, 12th man on the Laker bench--will be standing at the foul line. He’ll dribble the ball once, twice, three times, then maybe once or twice more. He’ll take a deep breath, then another.

He’ll look as if he has expended nearly his last ounce of energy, even if he has spent most of the game chatting with Billy Thompson instead of running with Magic Johnson.

All the while, the TV cameras will be focused on him, and Dick Stockton and Tom Heinsohn will be idly telling viewers of the slender 6-foot 7-inch, 190-pound player from Largo, Md.

Which is the whole reason Branch is stretching his free throws out for as long as he can.

“That’s a little trick I learned from Wes Matthews,” Branch said with a laugh. “Wes says if he gets to the line, he’s going to dip his head to the camera and show his wave.”

These days, Showtime casts a long spotlight for the Lakers, from superstar to simple scrub.

And Adrian Branch will proudly take his bows, too.

He remembers only too well what he went through to get here--the rejection slips from two other NBA teams, the bus trips in the minor leagues.

“I remember telling my home boy, ‘I don’t need the million-dollar lottery. I’ve got the Lakers,’ ” Branch said.

Too well, Branch also remembers who should be here with him, wearing the uniform of the Boston Celtics.

Len Bias. His teammate in college at Maryland. His roommate for a year. A player with a future of untold promise, chosen by the Celtics as the second player taken in the NBA draft.

“We were best of friends,” Branch said.

“The last day I saw him was th e day he was heading up to Boston. We were both at Maryland, lifting weights. That was the last time he ever said anything to me. He said ‘Goodby, Adrian,’ and he shook my hand, like this.

“It was something really special. I said to myself, ‘That’s kind of peculiar. He never said that. It was always, ‘Get back brother,’ ‘Be cool, man,’ or ‘I’ll see you later, Peanut Head.’ But he said, ‘Goodby, Adrian.’

“Three days later, he passed.”

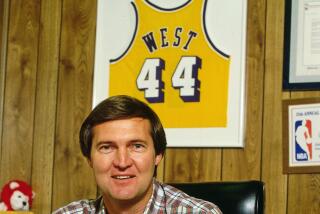

The first time Branch spoke with Jerry West, the Laker general manager, he was still in college, playing for Lefty Driesell’s Maryland Terrapins.

“He told me I had a lot of potential, but there were a lot of question marks,” Branch said.

“He said he didn’t know about my mental toughness or my dedication.”

Branch and West would not meet again until last summer, when West came to see him during an informal workout at UCLA.

In the interim, Branch’s dedication would be tested in ways he never dreamed. If nothing else, the Continental Basketball Assn. will do that for a player.

Meet Adrian Branch, Chicago Bulls reject, star guard for the Baltimore Lightning of the CBA.

“I remember after our opening night at home, we had a 23-hour van ride to Toronto,” he said. “Nine players, and luggage in one van that didn’t have any heat. It was December, and it was cold and rainy.

“I reached a point a lot of times where I said, ‘Man, is it really worth it?’ But then I would say, ‘Don’t turn back now.’

“I felt like a surfer riding a wave. I said, ‘I’m going to ride this wave and see where it takes me.’ ”

It helped that the ride began near home: Baltimore was just 45 minutes from Largo, and Branch lived with his parents when the team was at home.

“I have a strong family,” he said. “I got a lot of support.”

It helped, too, that the Lightning coach was Henry Bibby, the former star guard for UCLA who is now an assistant coach with the Washington Bullets.

“He really worked with me,” Branch said. “I really credit him for restoring a lot of my confidence.

“He told me this was a good time to work on a lot of things the NBA was going to demand from me. He told me to pick his brain for things they’re going to look for.”

One thing they’ll be looking for, Bibby said, was a player who can come off the bench. At first, the idea didn’t appeal to Branch.

“I said to myself, ‘This is the CBA and I can’t start down here?’ ”

Eventually, though, he realized how he could use that role to his advantage. He averaged more than 25 points a game for the Lightning, and in the playoffs was scoring more than 40 per game until he came down with fallen arches.

Chicago, which had drafted Branch in the second round, cut him on the day of the team’s first exhibition.

“I had my uniform in my bag when they told me I was cut,” Branch said. “But I had the feeling of being on an NBA roster, with an NBA uniform. That was a very motivating thing for me.”

When the CBA season was over, Branch was signed as a free agent by the Cleveland Cavaliers. This time, however, he didn’t even make it out of summer league before he was cut.

Branch was one of those “in between” players: too small for small forward, too big for shooting guard. His agent lined up a deal for him to play ball in Europe for a guaranteed $50,000. His parents told him it was a good idea. So did a close friend.

“He said, ‘I’m tired of seeing you being kicked. Go overseas, then come back in a year and try it,’ ” Branch said.

He would have gone, too, if it hadn’t been for Pat Bohannon, a Los Angeles woman in whose home Branch and John Wilkins--the younger brother of Atlanta Hawks star Dominique--had stayed as boarders during summer league

“She said she wanted to help me reach my dream,” Branch said. “She said to me, ‘You call yourself a Christian and believe in God. If your faith is strong, then He’s going to make it happen for you.’ ”

Branch remained in Los Angeles and, with the help of Bohannon, began working out at UCLA with such pros as Marques Johnson, Reggie Theus, Kiki Vandeweghe, and David Greenwood.

That’s when West came to see him again . . . and invited him to Laker camp.

“The morning he died, I had stayed up all night with my brother, Al, talking, just talking about life. I never stay up all night. Before I went to bed, it was unusually bright that morning. I went to the window and there was a bright star outside. The sky was really bright, too.

“I woke up at 8:51, on my own. He died at 8:50. As days passed, I realized there was a specialness. He was with me, I believe. My life with him was complete.

“I miss his friendship, but our friendship was complete. We laughed together, we cried together, we enjoyed success together. We shared a lot of special things together.

” . . . On top of that, he said goodby to me.”

“I was just thinking today,” Adrian Branch said, while eating scrod stuffed with lobster in a Boston restaurant, “that the 12th man on the Laker team is probably treated better than the star player of the Sacramento Kings.”

Such are the rewards of being a Laker. And the price?

“James Worthy was one of my biggest supporters,” Branch said, recalling training camp in Palm Springs. “Basically, we were the Southern boys, ACC guys.

“James would come by and tell me, ‘Don’t go down, boy, don’t go down. Don’t get injured. Don’t lay on the side like the rest of ‘em.’

“I knew from experience that if an 18-year veteran (Kareem Abdul-Jabbar) can be out there playing every day, then I knew a young boy can go out there, too.”

After surviving the final cut, Branch had an experience that taught him what it meant to be a Laker.

“One day we were messing around, we were on the elevator--me and James (Worthy) and Magic, and James had a McDonald’s wrapper and he threw it in the elevator.

“I threw it back at him, then we left. Magic told me to go back there and pick it up.

“It was just the fellas, you know what I’m saying? And it says a whole lot about a person’s character when nobody else is around.”

Branch played little for the Lakers this season. He appeared in 32 games and averaged less than seven minutes an appearance.

“You always live out your fantasy of being a star. One day being Magic running the show, or Byron shooting the long-range shot,” Branch said.

“But I’m content and patient, because of the experiences I’ve already lived through. I’ve been in the CBA. I can play the waiting game.”

While waiting, Branch drew on a memory from high school at DeMatha (Md.), where his coach, Morgan Wootten, used to designate a bench captain for every game, one person to keep everyone else’s enthusiasm going.

“My very first game as a pro, that thought came to my head,” Branch said. “I knew I wasn’t going to play much. (But) it would really have been silly for me to say, ‘I’m the bench captain.’ ”

Instead, Branch slapped a hand and said, “Pass it down for the bench,” while the starters were being introduced. Then one day, Michael Cooper picked up on it and exchanged high-fives with Matthews. Soon, the other reserves were doing it, they added a rhythmic clap, the Laker girls joined in, and eventually so did the Forum fans.

A tradition was born.

And for one shining day in February, so was a star. The Lakers were in the Capital Centre, a few blocks from where Branch grew up, to play the Bullets.

Even though it was still a close game, Laker Coach Pat Riley sent Branch into the game in the second quarter. The Lakers were behind when he went in, ahead when he came out. He also threw down a slam dunk for the home boys.

“I came out of the tunnel to walk to the bus after the game, but there were 80 people outside. My family, my friends,” Branch said.

“I said, ‘Man, I can’t get on this bus. It’s not enough just to say hello to everyone.’

“It was such a special time, from the time my Dad picked me up at the hotel. He had tears in his eyes.

“To me, staying in touch with people, my family and friends, is so important. Here today, so full of life, gone tomorrow. And when you’re gone, you leave no tracks.

“The best time of your life is here, now. I feel good about myself. I feel like the luckiest guy in the world, and justifiably so. I just want to be able to share my success with the people I love.”

“Even if he didn’t want the best, his talents wanted it for him. He was such a phenomenal talent, a blue-collar, Buck Williams attitude day in and day out.

“He was a basketball player. He was made to play basketball. He entertained a lot of people and made a lot of people happy. He did what he was destined to be: a basketball player.”

On June 19, 1986, Len Bias died of a cocaine overdose. He was 22 years old.

It is almost a year later, and Adrian Branch, 23, smiled at what it would be like if Bias were a Celtic today.

“I would have been sitting there so bad ,” Branch said. “I would have been saying, ‘Like Bias, stop shooting those airballs.’ It would have been so special.

“I would have been so proud of him, watching us both grow up into young adults. And he would have been proud of me, too.

” . . . There’s still a specialness. Him being a Celtic. The spirit of him being a Celtic. It’s not forgotten.”

More to Read

All things Lakers, all the time.

Get all the Lakers news you need in Dan Woike's weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.