Bell Takes Toll on Foes, but He’s Respected

- Share via

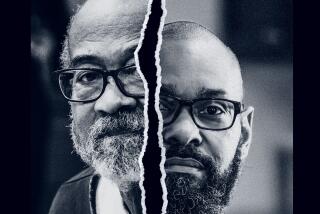

TORONTO — Toronto Blue Jays left fielder George Bell is a good player with a bad image.

“People that play against George don’t like him -- but they respect him,” said Toronto hitting coach Cito Gaston. “People who play on the same team with George love him.”

That, in a capsule, is the George Bell paradox. To know Bell is to love him, while those put off by the hard-shell, soft-interior native of the Dominican Republic believe him to be a brutish, insensitive hot-dogger.

Bell does not make it easy to refute the image, either. He is very defensive -- but in an offensive sort of way.

Some, not all, the writers who cover the Blue Jays regularly have found Bell much more approachable this season. To people he does not know well or trust, Bell will still respond in a gruff manner, “I don’t give interviews.” Then he gives you a couple minutes of polite nonsense about why he dislikes being interviewed.

“George Bell is a very good person,” his manager, Jimy Williams, said of the man who led the American League in home runs and RBI by June 23 yet who may make the AL All-Star team only at the whim of Boston Manager John McNamara. He was way down the list of AL outfielders in the early voting.

“Deep down he’s a humble guy, as far as helping people is concerned,” Williams said. “I know he helps the kids in the Dominican Republic a lot. With gloves, balls, bats or just his time. He’s a sincere guy, as far as doing things like that, not doing them to be written about or talked about.”

He plays hard and plays to win. In the clubhouse Bell is an expert needler and the object of his teammates’ obviously friendly agitation.

“When it’s quiet in the clubhouse, someone will direct a statement to him,” Williams said, “just to get him going. Or he’ll do the same thing to somebody else.”

Why then, does the private good guy have a public image as a bad guy who shoots from the lip? He also can be like this:

A man who will accuse Toronto writers of racism for voting Dave Collins the 1984 team MVP; accusing umpires of prejudice against Canadians and Dominicans after some close calls in the 1985 playoffs went against Toronto; throwing a tantrum early this season when Williams had him penciled into the lineup as the DH and Rick Leach in his left-field spot.

Perhaps it has something to do with a few of the same things that cause misunderstandings at the national level -- poor communication, lack of appreciation for the other guy’s position and background.

George Bell comes from the most famous producer of talent in the Dominican Republic, San Pedro de Macoris. Put yourself in his position.

You’re 18, speak almost no English and sign a baseball contract that will send you from an environment where you are totally comfortable into a place you have never seen before -- Helena, Montana, United States of America.

How many products of white, suburban United States high schools could handle being sent to San Pedro de Macoris to play three months of baseball at age 18?

Minor league farm directors will tell you most have enough problems just dealing with being away from home for the first time, let alone having to learn a new language while they’re doing it.

Some seasoned minor league players can’t handle their first experience with winter ball in Latin America.

“I speak a little Spanish,” said hitting coach Gaston. “But I remember playing winter ball one year, and even though I could speak enough to get by, I’d still do interviews through a translator. I just didn’t feel comfortable. Especially television or radio interviews. I’d still ask someone to translate for me.”

“It’s hard, very hard for you in a new country and nobody likes you,” Bell said. “My first year (in the Phillies’ organization) was terrible. The other players, both black and white, looked down on Latin players.

“They didn’t trust anybody who spoke Spanish. If you were Latin American, they said, ‘You crazy and you like to steal.’ There were only a couple of us who spoke Spanish and to be called names, well, it hurt. It hurt a lot.”

In 1980 Toronto drafted Bell from Philadelphia and kept him on its roster all season. The Phillies had tried to hide him but the Blue Jays’ Pat Gillick, now the club general manager but then a scout, was keeping up on Bell and noticed it when Philadelphia did not put him on its winter roster. Turned out to be a pretty good $25,000 investment and Toronto has made it a practice ever since.

Language has become less and less of a problem for Bell but residue from the early problems remains.

“I’ve complimented him for being an excellent player,” Williams said. “He may not like to answer questions sometimes but if he was an average player, he wouldn’t be asked them.”

“I’ve talked to him and he’s better about it,” Gaston said. “I told him, ‘I know you’re not comfortable with it (being interviewed) but you have to deal with it. Do it as best you can.’ He’s comfortable talking with most of our sports writers. With others, he clams up a bit. He’s trying, he’s making an effort to change that.”

Catch Bell near the batting cage or in a loose moment in the clubhouse he’ll like as not chit-chat until it’s time to move on to the next phase of his pregame routine. When he gets gruff is when you ask him to sit down for an interview.

Nearly gone are the ‘Do that again and I kill you’ or ‘You crazy, man’ expressions that used to keep people away a couple of seasons ago. He is getting more and more comfortable in non-baseball settings but still keeps that barrier up.

Some players don’t care for the way Bell plays with his heart right out there for everybody to see. The way he takes every out or failure to move runners as a personal affront, the way he crumples to his knees or flips his bat when fooled by a third strike.

“George plays hard. On the field he dedicates his energies to winning,” Williams said. “He’ll do whatever it takes on each particular at-bat, each play, even down to telling another hitter what the pitches are doing . . . sinking, running, cutting, tailing.”

Bell is also mistakenly seen as a pure athlete, in contrast to more affable teammate Jesse Barfield whom people view as a self-made, thinking man’s player. Not so, say both Gaston and Williams.

“George figures out what pitchers are doing,” Williams said. “He can hit a lot of (different) pitches in different areas and hit them with authority. I think he listens to Cito a lot.”

“George will look for a pitch,” Gaston confirmed. “I know that. He likes to tease me that he doesn’t know what kind of pitch he hit. But he knows. He just loves to agitate me.

“He doesn’t guess. He goes up with an idea of what’s coming, what pitchers like to throw him in certain situations.”

The numbers support that. His home runs the last three seasons have gone 26, 28, 31. His RBI count has risen from 87 to 95 to 108. Last season he hit .300 for the first time.

He has played third base without complaint (he regularly takes grounders there during infield practice) and you never hear a word about the pounding his sore knees take on Exhibition Stadium’s artificial turf.

But you will hear about it if you try to DH him, which Williams found out earlier this season. Williams had Bell down for DHing with Rick Leach scheduled for left field. Bell threw a tantrum and his bat when he learned of it after arriving at the ballpark.

Williams wasted no time explaining he wanted to give George a semi-rest, he just made Leach the DH and put Bell back in left. The initial reaction was that Bell had challenged Williams’ authority and won, a potentially fatal incident when your club is challenging for first.

“George Bell will speak his piece, no doubt about that,” Williams said. “But that’s OK. I respect him for that. But in that particular situation I don’t think he was challenging. He feels DHing degrades him. It lessens him as a player and hurts his value as a player. I just hope in September he’ll understand what I’m trying to do.

“That situation might have stalled us for a 24-hour period. But maybe it was healthy for the club at that particular point. Whatever, that’s behind me. You can’t look back. You can only try to better yourself.

“When I think of George Bell I can’t help but think back to 1981, when we had to keep him on the roster all year. I don’t know how many fly balls I hit him. But he would bang the wall. And to me, you can’t be a good outfielder unless you bang the wall.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.