Minister Omnipotentiary : REFLECTING ON THINGS PAST <i> by Peter Lord Carrington (Harper & Row / A Cornelia and Michael Bessie Book: $22.95; 406 pp.; 0-06-03090-5) </i>

- Share via

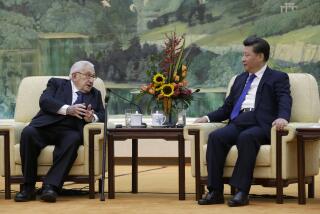

There are few foreign affairs leaders as highly respected as Peter Lord Carrington, NATO’s secretary general from 1984 to 1988 and Britain’s foreign secretary in the early years of Margaret Thatcher’s service as prime minister. In his preface to Carrington’s memoirs, former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger writes that no world leader “has impressed me more.” Don Cook of The Times has written that Carrington “seems almost too good to be true.”

Readers of his autobiography will not find a large number of clues as to why the sixth Lord Carrington, a man who has never been popularly elected to any office more exalted than the Buckinghamshire County Council, has been so politically prominent in every Conservative government since 1951 in jobs including minister of defense, minister of energy, Conservative Party chairman, leader of the House of Lords, first lord of the Admiralty and High Commissioner to Australia.

Carrington does not boast. To Kissinger and others, he represents the British tradition of almost selfless public service. One of his strengths is his sense of principle, his willingness to resign a position when he believes that the needs of country, party or conscience demand it. The U.S. government does not have such a tradition of resignation from office.

Carrington’s test of conscience came in 1982 when Argentina challenged Britain by suddenly invading the Falklands. Although Carrington had wanted the job of foreign secretary as no other, he quickly resigned. In explaining his action over the Falklands, Carrington writes that the nation feels disgraced in such times, “Someone must have been to blame. The disgrace must be purged. The person to purge it should be the minister in charge. That was me.”

He was later vindicated by the Franks Report, which pointed out his prior warnings of danger. He does not spend much time explaining the Falklands crisis. Kissinger writes that when he remarked to Carrington that he had never mentioned his private warnings on the Falklands after the invasion, Carrington replied: “There is no sense assuming responsibility if you then whisper that you’re not really responsible.”

Carrington learned responsibility early--at his country home, at Eton, at the royal military college at Sandhurst (unlike most party leaders, he did not attend university at Oxford or Cambridge) and as a young officer in the elite Grenadier Guards. He neglects to mention that he landed on the beach at Normandy on D-Day or that he was awarded the Military Cross. He writes little about his parents, his children or of Iona McClean, his wife for 47 years.

Instead, he has written a largely public autobiography about his public service. For instance, he almost never mentions money. But what else than access to inherited or easily acquired wealth can explain his seemingly effortless ability to spend most of his life in the House of Lords and move from one public position to another? Most American leaders, even Henry Kissinger, have to scramble a little to pay the bills. The ability of Her Majesty’s government to tap the civic spirit of the London-oriented rich is one reason why the British develop such an experienced cadre of political leaders. Americans can only envy such governmental continuity.

Carrington’s book displays some of the qualities that led to success in most of the jobs he tried--his lively intelligence, lack of egocentricism and good humor. Above all, with the easy confidence of some of the wealthy and well-born, he speaks well of almost everyone. “It may be a defect in my temperament that I find it much more natural to like than dislike the people I work with or for,” he confesses.

He is full of praise for three of the prime ministers he served, Harold Macmillan, Sir Alec Douglas-Home and Edward Heath, as well as for his Labor predecessor as defense minister, Denis Healey. He is not high on Anthony Eden, whose manner he calls “neurotic,” or Ian Smith, the white leader of Southern Rhodesia, where Foreign Secretary Carrington helped achieve a settlement giving power to the black majority. He seems to view Margaret Thatcher as something of a hard-hearted, right-wing ideologue, but he is careful not to say so exactly. He amply praises her accomplishments.

Given his generally sanguine views of British politicians, civil servants, farmers and soldiers, it is surprising when he writes that too much of British behavior is now “loutish . . . I sometimes have the impression that British manners have become the worst in the world.” One recalls that (and why) British soccer teams are barred from competitions on the Continent, and yet one wonders: Has Carrington recently visited a Manhattan street or a North American ice hockey match?

The author has written an often pleasant, easily read book that tells much about modern international politics and the United Kingdom’s government. Carrington has accomplished much during his nearly 70 years, and he offers no recriminations or regrets. He is proud of his work to strengthen the Western alliance, to preserve the British nuclear deterrent and to improve NATO military capacity. He thinks it now inconceivable that there could be another war among the Western European powers and believes that, globally, nuclear weapons have prevented war. Indeed, while he predicts there will be minor wars outside Europe, he does not believe a major war will occur again if East and West remain balanced and if the West remains strong.

Although highly regarded in most capitals, Carrington did acquire enemies--in white Africa, in the Mideast and at least one in Washington. Early in the Reagan Administration, the Washington Post reported that Secretary of State Alexander M. Haig Jr. had called Carrington a “duplicitous bastard” in a staff meeting. Ever the even-tempered gentleman, Carrington turned the other cheek to the grouchy general.

While Haig has passed on to the obscurity that some think he deserves, Carrington went on to NATO and to receive the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President Reagan last year. The President said that Carrington’s “efforts on behalf of us all during the past four years have set a new standard.”

Even in politics, merit is sometimes rewarded.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.