Losses Burden Builder of Weight-Lifting Equipment : Bankruptcy: Icarian Fitness filed for Chapter 11, hoping for an infusion of cash, but a dispute with a former partner clouds the prospects.

- Share via

Perhaps the low point of his company’s bankruptcy filing came several weeks ago when Howard Briles got on the phone with a customer who’d heard Briles had died.

The customer was wrong, of course, but that was not consolation enough for Briles--owner of the gym equipment company Icarian Fitness in San Fernando--who said the rumor was spread recently by competitors he declined to name.

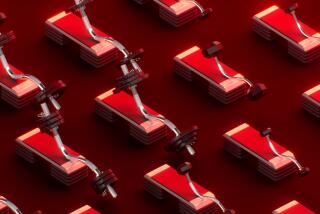

Icarian, a 12-year-old company whose losses ran into six figures on sales of under $4 million in 1989, makes weight-lifting machines along with racks and benches for use with barbells. According to its Jan. 2 Chapter 11 bankruptcy filing, the company has total assets of $456,046 and total liabilities of $742,668.

Even though any bankruptcy reorganization approved by the court could rob Briles of control of the company he helped build, he said if it keeps the company alive, ends a string of losses and helps attract a badly needed investor to the company, all the grief will be worth it.

But Icarian has two messy problems to solve first. The company grew so fast, Briles concedes, that its management was sloppy, and until recently it lacked controls on inventory and production. As a result, it was plagued with late shipments and even the theft of finished equipment. Icarian still hasn’t shown it can recover from those problems and make gym equipment at a profit again. Plus, Icarian is in a nasty dispute with former partner Karl Johnson over a $339,000 mortgage on the building that houses the company.

Briles, 45, is a beefy man who said he’s been lifting weights for 30 years and who once taught gym classes in a Pacoima junior high school. Briles and Johnson started the company with about $500 apiece, which they used to buy welding equipment to custom-build lifting sets they sold for a few thousand dollars.

Icarian, a small but well-known company in a market dominated by Nautilus and Universal, sells equipment--which averages about $900 a piece--to commercial gyms, schools and hotel fitness centers where it gets heavy use.

Some of the company’s strongest loyalists are hard-core bodybuilders who are attracted to the 2-inch by 4-inch steel frame construction of Icarian’s weight machines. The big beams are a marketing gimmick that has succeeded, said Mark Nalley, president of Flex Dynamics Gym Equipment in Anaheim, a competitor of Icarian’s. “The belief that bigger is better seemed to work for them.”

But about two years ago Icarian began to lose money despite increasing sales. Icarian’s chief financial officer, Mark Bruno, said the company’s sales grew from under $1 million in 1986, when it operated with a very small profit, to just under $4 million in 1989, when its losses ran into six figures.

Briles said part of the problem was that he concentrated on selling machines and was too slow to hire professionals to manage production costs. So in June the company hired Bruno, an independent business consultant, as CFO and chief operating officer to help clean up the company.

But the problems had become so bad by early 1989 that shipments to buyers were sometimes six weeks late--occasionally delaying or missing the grand opening of new gyms that had planned to use Icarian gear. Worse, Icarian may have lost hundreds of thousands of dollars in equipment and supplies to theft last year alone. But the lack of good record keeping makes it hard to measure the losses. Just as bad, purchasing was haphazard--the company recently discovered a stockpile of 2,000 gallons of paint that it can’t use.

Icarian’s manufacturing workers have suffered from the problems more than anyone. Since June, 40 of the 100 who assembled weight machines have lost their jobs, some by attrition but most through layoffs, in an attempt to cut costs.

Since coming on board, Bruno has scaled back production so that equipment is made only as it’s ordered. He’s insisted on tracking how fast orders are filled, how much labor it takes to fill them and exactly how much steel and paint goes into them. And he’s come up with a business plan he claimed will make Icarian very profitable in the next few years.

Bruno and Briles say that what Icarian needs to really get back on its feet is capital--about $1 million. But that’s where the dispute with former partner Johnson comes in. Briles claimed that the main reason for the bankruptcy filing is to clear Icarian of responsibility for debts he said only Johnson is liable for and to ease the fears of potential investors.

Briles and Bruno cast Johnson as the heavy in this business drama. Not surprisingly, Johnson--an actor who credits his vaguely sinister mustache, shaved head and conscientious weightlifting with winning him roles as a heavy on TV shows such as “T.J. Hooker”--said he isn’t playing the bad guy in his dealings with Icarian.

The dispute goes back to 1987 when Johnson and Briles got a $339,000 loan from the federal Small Business Administration (SBA) to help buy the building that houses Icarian. But when Johnson and Briles decided to go separate ways in July, 1988, they agreed essentially to split their holdings in half: Briles would take Icarian and Johnson would take the building.

Icarian would pay rent and taxes on the building, but Johnson was to take responsibility for the mortgage. Briles and Bruno claim that Johnson hasn’t done the paper work to take over that responsibility and add that the $339,000 debt to the SBA still on Icarian’s books makes the company look like a bad bet to potential buyers.

“He’s made it impossible for us to go out and get investors,” Bruno claims.

“This is basically totally false, front to rear,” Johnson says of the claims.

Strangely enough, it’s not responsibility for the loan that Johnson denies. In fact, he said he will pay it off, and agreed that the mortgage is no longer Icarian’s responsibility.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.