A Tough Fielder’s Choice: Hit a Ball or Hit the Books : Preps: A player can forgo college to sign a professional contract after high school. But the decision isn’t an easy one.

- Share via

Greg Pirkl looks in the mirror and envisions himself in the major leagues. He’s playing in the Kingdome for the Seattle Mariners, hitting home runs and throwing out would-be base-stealers.

At those times, Pirkl knows he will reach the goal so many players only dream about. And he has no regrets about his decision to turn professional after high school.

There are days, though, when the curveballs are wicked and the fastballs blow past him. There are days when his knees ache from the constant crouching he must do as a catcher for the San Bernardino Spirit, a Class-A team for the Mariners.

On those days, as rare as they might be, Pirkl has one thought:

“Geez, I wish I went to college.”

High school football and basketball players, even the cream of the crop, are required to go to college--with rare exceptions--before a professional team will consider drafting them.

But the sport of baseball, with its minor league system, employs more players than other sports.

In the amateur draft each June, thousands--including many high school seniors--are selected and then tempted with offers of money and other considerations.

The options can be confusing, especially for a teen-ager faced with a decision that will affect the rest of his life.

In 1988, Pirkl, then a senior at Los Alamitos High, was a valuable commodity--a catcher who could hit and hit with power. College recruiters and professional scouts came in droves to Griffin games, drooling over the prospects of signing this prospect.

Pirkl was courted by recruiters, and pro scouts whispered in his ear. First, he signed a letter of intent to go to USC, and then the Mariners made him their second-round pick in the draft.

At 17, Pirkl had to choose between learning and earning.

“There were so many things to consider,” he said. “I was new to catching, so I thought going to college would help me learn the position. But going to college wasn’t just playing baseball. It meant finding a job, and it meant passing classes.”

So Pirkl signed for a bonus in the six-figure range.

“I didn’t want to look in the mirror some day and say, ‘What if?’ ” he said.

A high school player who is drafted can be signed until the first day he attends classes at a four-year university. After attending his first class, he is untouchable for three years. The player can be drafted again after his junior year or when he’s 21.

He could also opt to play at a community college, which would make him eligible for the draft each year.

So there are numerous options available. The trick is picking the right one.

“There was a time when everyone who was drafted would sign,” Cal State Fullerton Coach Augie Garrido said. “Now, some are deciding to go to college instead. I don’t think we’re working in direct competition with professional baseball. The hope is that the player will reach his full potential by the route that’s best for him.”

To professional baseball officials, the best route is through the minor leagues. And the best time to start is now.

“From a major league baseball perspective, we prefer a player to turn pro out of high school,” said Richard Brown, president and chief executive officer of the Angels. “First, it gets them away from aluminum bats. But it simply gives us four more years with a player to teach him to be a major league player.”

And professional scouts usually have little trouble convincing an athlete of this.

“You have to understand that every young baseball player has a dream of playing in the major leagues,” University of Miami Coach Ron Fraser said. “When someone is holding that dream in front of them, it’s tough for a kid to say, ‘No, I don’t want the thing I’ve been dreaming about all my life. I’m going to college.’ It doesn’t work that way.”

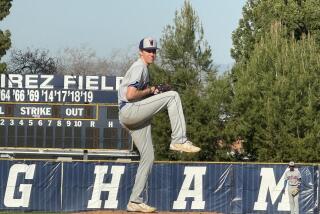

Derek Fahs, a senior at Fountain Valley High, is considered the top pitching prospect in Orange County. He has a fastball that has been clocked around 90 m.p.h. and a good curveball.

He is expected to go high in June’s draft. For the past year, he has been weighing the idea of a college education against signing a professional contract.

“Education is definitely important, and I’m keeping that option open,” Fahs said. “I really want to turn pro after high school. It would be the ultimate goal, but it depends on the money.”

Fahs, like most drafted players, is relying on his parents to help him with the choice.

It is the logical place for a kid to go for advice. While a player usually consults his high school coach, parents have the most input. But many times, the discussion is thrown back with a question: “What do you want to do?”

“An 18-year old kid doesn’t have the experience to make that decision,” USC Coach Mike Gillespie said. “Hopefully, the parents are in a good position to make a sound judgment. So often what we see happening is parents saying, ‘You’re 18. You have to lead your own life, so make your own decision.’ That’s unfortunate.”

In 1989, while a senior at Magnolia, Robert Camarillo was drafted in the 29th round by the Texas Rangers. He also received an offer for a partial scholarship from Pepperdine and was courted by Rancho Santiago coaches.

After Camarillo talked it over with his father, he opted for the Rangers and received a $10,000 signing bonus.

“My dad and I figured that I might never get the chance again,” Camarillo said. “It could have been a once-in-a-lifetime shot.”

Camarillo played one season for the Rangers’ Rookie League team and one season of Class-A ball. He was released this spring and is now attending Cypress College, driving the sports car he bought with his bonus.

“Looking back, I think I should have gone to Rancho Santiago,” Camarillo said. “Some guys that I played with improved, and their value has gone up big-time. I don’t think about it every night, but I think about it.”

Said Cypress Coach Scott Pickler: “The kids see the glory, and they see the money. But they don’t understand how tough it is in the the minor leagues.”

Mike Robertson understood, but then he has a father who provided him with first-hand information. Robertson, a junior first baseman for USC, was drafted by the Angels in the 13th round when he was a senior at Servite.

An Angel fan all his life, Roberston thought it was destiny.

“I wanted to be a professional baseball player, and here the team I had followed picked me,” Robertson said. “They even made me a real good offer. It was tough to walk away, but my parents were steering me to college.”

Mike Robertson Sr. was a graduate of Boston College and played in the Washington Senators’ organization for a few years. He reached the triple-A level before a shoulder injury ended his career.

Knowing the pitfalls of professional baseball, Robertson was determined to make sure his son received an education, despite an offer of a signing package worth approximately $100,000.

“My dad had a degree to fall back on when his career was over,” Roberston said. “He always told me what a hard life it was in the minors, especially the long bus rides. I had a great example of how important a college education is.”

Said Fraser: “The days of the self-made man, the guy who worked and didn’t go to college, are over and parents know it. A kid in the ‘90s has to have a college education.”

According to Bill Bavasi, director of minor league operations for the Angels, parents of players are expressing their concerns about education more and more. He also said that, in the past, professional baseball was viewed as uncaring in that regard.

Bavasi said teams often offered scholarship money to players, but they were limited to $1,500 a semester for eight semesters. To compensate, teams would offer a higher bonus to players who had signed a letter of intent.

“The only thing we could do was throw dollars at them,” Bavasi said. “It made us look like we weren’t concerned about education. We were scaring a lot of parents (of players) off.”

Two years ago, the restrictions on what a team could offer were lifted. The limit of eight semesters is still intact, but now a player can get the cost of his college education picked up by a team.

The College Scholarship Fund goes through the commissioner’s office. A player is eligible for his money if he starts school any time between his signing and two years after his last professional season.

When the player enrolls, the school contacts the commissioner’s office, which then bills the team.

Of course, the dollar figure differs from player to player. As with a signing bonus, the higher the draft pick, the better the negotiating leverage.

Pirkl, a second-round selection, had an agreement with the Mariners to pay for his schooling at USC, where tuition is $14,500 per year. Camarillo has an agreement of $1,000 per semester.

“If a kid has signed with Stanford, we will give him eight semesters at Stanford,” Bavasi said. “Let’s say the tuition is $10,000. We’ll add 4% to that, for tuition increases, and we have a deal.”

Even if a player hasn’t signed a letter of intent, a team will cover the cost of his education at any school. The only requirement is that the player demonstrates that he can get accepted and do the work.

“We’re not going to agree to pay for four years at Stanford to a kid who just graduated with a GED (the equivalent of a high school diploma),” Bavasi said. “But we will work with a kid and his parents.

“It works out well for the players. Many times, there are kids who aren’t ready for college when they come out of high school. They need a few years to mature.”

Marc Newfield, a teammate of Pirkl’s at San Bernardino, said he fit that category. A first baseman for Marina High last year, Newfield was recruited by every major college. But he said he didn’t score high enough on the SAT to qualify under NCAA regulations.

His problem was solved by the Mariners, who made him their No. 1 pick. Dee Newfield, his mother, insisted that the Mariners include money for college in their offer.

“I know the percentage of players, even ones picked in the first round, who make it to the major leagues,” Dee Newfield said. “I wanted to make sure his future was secure. I wanted him to continue with school, but he wasn’t ready. But he has that to fall back on.”

College coaches say the College Scholarship Fund is a step in the right direction. But some also say it’s unlikely many players will take advantage of it.

With instructional leagues and winter ball, a player won’t have time to go to school until his career is over. Coaches say that after four or five years of professional baseball, a player won’t want to go back to school.

And those who do want to continue their education won’t be able to.

“There’s no time to go to school while you’re playing,” Fraser said. “Not if you want to get through it (school) in four or five years. So you have to wait until you’re done playing. Then, what if you’re married? What if you have children? Will you be able to go to college and feed your family?”

Pirkl, now 21, faces those problems.

He said his contract states that he had to start school within 18 months of signing. But he played in the instructional league the first two years and the offer expired.

Pirkl has other considerations now, which would make college difficult to fit in. He has a son from a former relationship. That, he said, requires him to make it to the major leagues.

“If I get there, then I can take care of my family,” he said. “Every day I wake up, I have to believe that I will make it to the big leagues. If I don’t, I might as well give up now and get a job.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.