The BIG BOPPER : Slugger Scott Talanoa’s long home runs and .440 batting average make him a favorite of CSULB fans--and pro scouts.

- Share via

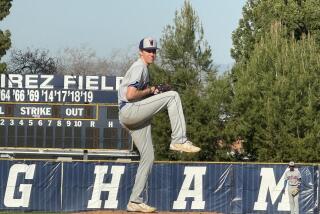

As if launched, the ball soared majestically toward left-center field at Cal State Long Beach’s 49er Field and descended far beyond the wall. Another 400-foot home run for Scott Talanoa, who is a sight to behold himself.

Although that homer Friday afternoon against UC Irvine was the eighth of the season for Talanoa, the 49ers’ 6-foot-5, 240-pound junior designated hitter is not a swing-from-the-heels, all-or-nothing slugger.

He used to be. As a Little Leaguer, when he was 12 and already 6 feet tall, he wasn’t allowed to use an aluminum bat partly out of fear that he might hurt someone with a line drive. So he hit 24 homers with a wooden bat.

Now, at 21 and as large as a monument, Talanoa has a short, compact swing. And he wields a metal bat (no other type is allowed in college baseball) with an artistry that has produced a .440 batting average, best in the Big West Conference and 14th in the nation. His 57 RBIs lead the 49ers, who are 35-13 overall and 10-2 in the Big West and ranked third nationally.

“I think he’s gotten a lot better,” Long Beach Coach Dave Snow said of Talanoa. “He’s shortened his swing, and that has given him good hard contact. He hits for some power, but the most impressive thing is that he’s hitting for average. He’s hitting good breaking balls and good fastballs.”

And he’s struck out only 18 times in 150 at-bats.

A graduate of El Segundo High School who lives in Lawndale, Talanoa is unique in that he is a huge, young athlete of Samoan descent who does not play football. “There’s not too many of us (in baseball),” he said before a recent practice. “There’s too much agility (required in baseball) if you ask me. Most Polynesians play football. Football wasn’t my thing. I played at El Segundo but couldn’t handle going out every day and trying to kill somebody.”

Except to the pitchers he faces, this is a gentle giant whose dazzling white smile radiates a warmth against the cool spring winds.

“When I first came here, I was intimidated by him,” said teammate Steve Whittaker. “But he’s a pussycat, one of the nicest guys you’d meet.”

Apparently, only failure at the plate can set Talanoa off. After popping up to the catcher while attempting to lay down a surprise bunt against Irvine, Talanoa repeatedly pounded his bat into the ground. But such tantrums are rare. “I’m not a hothead,” he said. “I don’t get mad very easy. I try to be happy as much as I can.”

Said Snow: “He has a relaxed intensity I like to see in a player. He will vocalize if we have a letdown. They pay attention to what he has to say.”

Talanoa was born in Inglewood, lived in Compton until he was 6, then moved to Lawndale. Growing up in rough areas, he said, “You survive or you die. That’s the way I take it on the field--it’s me against the pitcher. If I win, then I can stay alive for another time.”

After an all-CIF career in baseball, basketball and football at El Segundo, Talanoa received a baseball scholarship to Cal State Fullerton. But Coach Augie Garrido, who had recruited him, soon left for the University of Illinois and Talanoa didn’t fit into the new coach’s plans. A year later, he left for Orange Coast College, where he hit .401 with 19 home runs and was a junior college All-American.

Snow then persuaded him to come to Long Beach, where he sat out last season as a redshirt.

“When I was in high school, Dave used to come and watch me play, and he watched me play in junior college,” Talanoa said.

“He asked if I wanted to play for the Beach and I said, ‘Heck yeah, I’ve always wanted to play for you.’ He plays hard and it’s an intense game. You beat your opponent and then you’re happy. And if you happen to lose, as long as you play hard and do your best, you can still be happy. I can handle that because that’s my philosophy of life.”

Snow has been a big influence on Talanoa, as has assistant coach Bill Geivett, who spends long hours helping the player with his hitting mechanics.

But no one has made a bigger impact on Talanoa than his father. “Dad is a major figure in my life,” he said of Aiulu Talanoa, a sergeant in the Inglewood Police Department’s vice division who grew up in Samoa playing softball. “We are really really close. When I’m not doing good, he’s there for me. He’s here every day.”

When Talanoa was a high school sophomore, his father made him realize for the first time the hard work and dedication the sport would eventually require.

“My dad was mad,” Talanoa recalled. “I had a bad game the day before. We went to a batting cage and he made me hit for an hour and a half straight. I had blisters and my hands were bleeding. The blood was coming through my batting gloves, but he didn’t care. We went home and he took care of me, he soaked my hands. That was the only time he’s ever pushed.”

Talanoa was a pitcher in high school, but, as a designated hitter, has been a man without a position since. “It doesn’t bother me because I know my role on the team. It doesn’t bother me just having to hit because that’s what I’ve done all my life. I love to hit.”

But he knows that he would probably be required to play a position in order to reach the pros. “I know I can play first base,” he said.

He played first base last summer for the Mat-Su Miners in the Alaskan League, where, as the tallest, most powerful player, he acquired a Bunyanesque mystique.

“I had a blast,” said Talanoa, who went to Alaska, like many college players, to improve and play against good competition. “You get up there and the first thing that was really a trip was that the sun didn’t go down. It was 2:30 in the morning and still light. The air is clean, and everything was really green. You don’t see that stuff down here. We were in a valley 30 miles outside of Anchorage. It was awesome. The people would come out. We had good fans. They liked me, the little kids liked me.”

Now he has become a favorite of 49er fans, who marvel at his mammoth home runs.

“I don’t know why the people like me,” he said. “I just come out here with the intention to do my job every day.”

A couple of weeks ago, he hit a homer at UC Santa Barbara that went even farther--about 440 feet--than the one he hit in Friday’s UC Irvine game.

And the next day in batting practice, he hit a drive that cleared the left-field wall by 50 feet and smashed into a trailer. “You could hear the impact,” said James Lotter, a 49er media relations assistant. “I would have loved to have gone over there to see the dent.”

What’s the farthest he has hit a ball?

“I don’t know,” Talanoa said, laughing. “As long as it gets over the fence. As long as they score the runs and we win, that’s all I care about.”

Talanoa hopes he will be selected in the June amateur draft so he can begin his professional career. He knows of only one Samoan who has made it to the big leagues. “I can’t think of his name,” he said. “He pitched. He was in ‘the Show’ for 30 days in the ‘70s. I have no knowledge of any other Samoans that are even in the minor-league system.

“(To make it) will be good for me and my nationality. To show that we’re just not big people who play football. Or big people that like to fight.”

If a baseball career doesn’t work out for him, he said he would take advantage of his criminal justice major and follow in his father’s footsteps and become a police officer.

“I’ve always wanted to be a cop,” he said.

After Talanoa hit the long home run against Irvine, John Alls, 55, his flared trousers dragging in the dirt, retrieved the ball and walked hurriedly back to the grandstand behind home plate. Alls fetches balls hit out of the park to help the school save money.

Aiulu Talanoa, a gray-bearded bear of a man, has seen Alls do this many times, and it is always a pleasant reminder of the progress his son has made since that memorable day long ago in the batting cage in Carson.

“I just tell him to keep on working,” the elder Talanoa said softly a few innings later. “I hope it works out for him. If it doesn’t, we won’t be able to say we didn’t try.”

He turned back to the field, standing behind the screen as usual, watching Scotty grow.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.